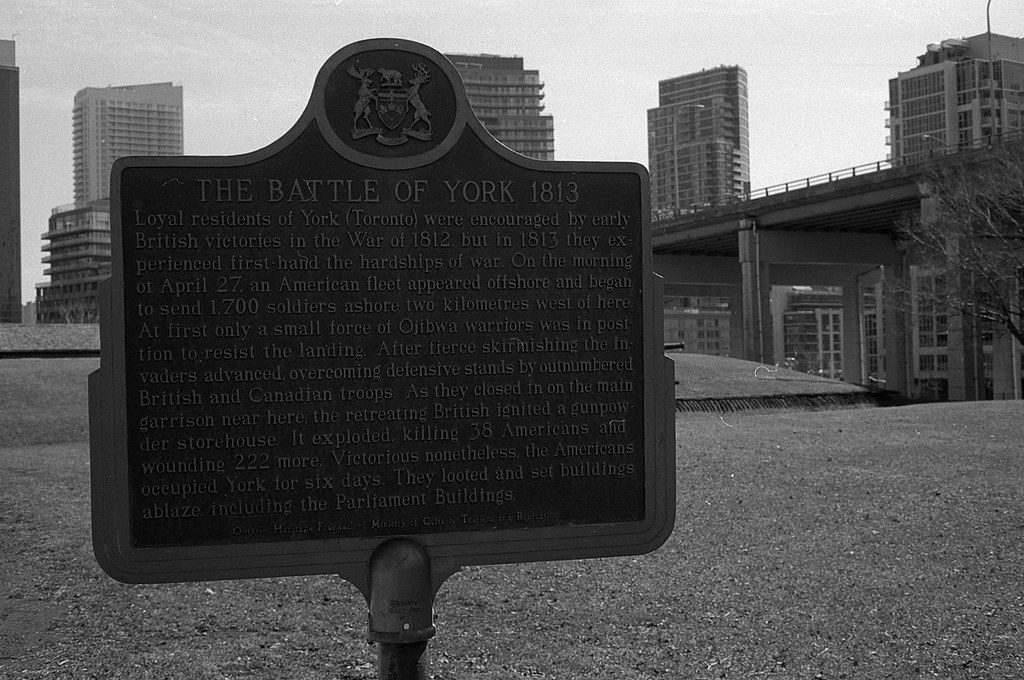

A watershed event for the Canadians during the Anglo-American War of 1812. The tiny town of York, today’s Toronto, Ontario, was the colonial capital of Upper Canada, established in 1793 by John Graves Simcoe for the sole purpose of being further away from the American frontier. Despite the town’s status as the capital it was poorly regarded called Muddy York, a far cry from the seat of British power in North America, Quebec City. And while the town itself was far from a tactical target, it wasn’t a tactical target that US Army commander, Henry Dearborn, wanted following a series of American defeats in 1812. He needed a victory that could lift the spirits of his flagging army. And what a better victory than the claim of capturing the capital of Upper Canada.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

The spring thaw was the only single the American invasion fleet needed to launch their planned attack against York. Though Dearborn was at odds with his naval counterpart, Commodore Isaac Chauncy, on the target. Chauncy wanted to attack the major and much more tactically sound target of Kingston to eliminate the British naval squadron on Lake Ontario. That squadron’s flagship, the H.M. Sloop Royal George (20) had given him the slip late in 1812. And while Dearborn at first agreed, a false report to the troop strength at Kingston turned him towards York. And on 26 April 1813, the American squadron had been spotting just off the Scarborough Bluffs, and a warning sent to General Roger Hale Sheaffe.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

General Dearborn was an old and sickly commander and preferred to let younger men lead the initial charge. For the first wave of the attack, he put the young and freshly promoted General Zebulon Pike in command. To clear the way, Pike ordered Major Benjamin Forsyth of the 1st US Rifle Regiment into the landing craft to conduct their landings. Sheaffe had ordered his Mohawk warriors into the woods around the old Fort Rouille. Upon spotting the American landing craft, the Mohawks began harassing fire. Forsyth, not wanting to waste ammunition ordered the boats to drift further along the shore before landing. The riflemen, like the Mohawks, were well versed in woodland, irregular combat. And soon had the Mohawks on the run, as they came into the clearing of the fur fort, they met with an untimely surprise, Sheaffe had deployed Captain Neal McNeale’s grenadier company of the 8th (King’s) Regiment. The crashing volley forced the riflemen to take cover in the woods. From cover, the riflemen could easily avoid the drilled volleys from the regulars and picked them off with ease. With McNeale and one of his sergeants dead, the remaining troops made a final desperate bayonet charge.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

Seeing the success of the 1st Rifle Regiment, Pike ordered the remainder of his division into their boats as he joined them on the land. The delay was enough for Sheaffe to bring up the rest of his troops including the light company of the 8th, the Royal Newfoundland Regiment and supported by Militia and Glengarry Light Infantry troops. The clearing rang with the sound of exchanged gunfire as the Britsh and Americans battled to a near stand-still. As Pike’s division continued to land the situation turned on the British, and Sheaffe ordered a full retreat to the still firing Western Battery to put up a second line of defense there and hoped that the militia under General Shaw had arrived. The militia it seemed had gathered in a ravine near the garrison but refused to move, fearing for their property.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

The situation at the western battery was far worse than Sheaffe had realized. The wounded and dying mingled in with Sheaffe’s fighting troops and somewhere in the chaos before the Americans could arrive the portable magazine blew. It seemed a spark landed on a powder bag setting off the whole magazine spreading death to any nearby. Not realizing this, Sheaffe feared that all was lost and ordered all British troops to retreat and sent an officer of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment to blow up the main garrison’s powder magazine. In confusion, Sheaffe failed to order that the Royal Standard removed from in front of the Government House. Sheaffe did leave orders for the town’s militia officers negotiate for the town’s surrender. As the British headed east, Pike was lining up to lay siege to the garrison as the flag still flew above it.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

The Americans moved in for the final blow, Chauncy’s ships suppressed the British shore batteries that had caused little damage giving Pike the advantage to set up his artillery to bombard the garrison. The one thing that the Americans did not realize was that the garrison had already retreated. The world exploded as the grand magazine blew sky high, killing British and American alike inside an 180-meter kill zone. General Pike found his dreams of glorious battle literally crushed as a stone landed on him. Pike would live long enough to be ferried back to the American fleet, his head resting on the garrison flag torn off the pole outside of Government House. The angered Americans began to hunt the town’s militia, locking them inside a surviving blockhouse while three officers, Colonel William Chewette, Major William Allen, and Captain John Beverley Robinson surrendered to the acting commander of the American troops at York, Colonel Mitchell. The negotiations had been going well until word reached the group that the HM Sloop Isaac Brock (20) under construction in the town docks was ablaze. But as night fell, many of the American officers departed for the fleet, leaving the regular troops ashore to scrap together shelter in the ruined garrison. The troops did not stay in the garrison and instead moved into the town and began to plunder and destroy; they even opened up the town’s jail releasing those inside. They also broke into the Parliament Buildings taking with them to governmental mace, a golden lion figure, and the wig of the house speaker. This was all to the annoyance of the town’s rector, the Reverend John Strachan. Reverend Strachan went directly to Dearborn the next morning blaming the aged general for the conduct of his men. But Dearborn was not to be bullied by a mere pastor, instead ordered that a new set of surrender orders be negotiated this time with his representative the young naval officer, Lieutenant Jesse Elliot.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

Another day went by without a formal surrender, and while the town was under heavy guard by the men of the 1st US Rifle Regiment, it was the former occupants of the town jail. Fuelled by anti-British sentiments that went on their spree of violence on the town, setting fire to the Parliament buildings, an act often blamed on the Americans. The residents of York found their town reduced to ashes by the time Dearborn signed the surrender order on the 29th. To add insult to injury, the Americans proceeded to strip the town’s warehouses of any military supplies and destroying any defensive emplacements.

Minolta Hi-Matic 7s – Rokkor-PF 1:1.8 f=45mm – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Ilford Perceptol (1+1) 15:00 @ 20C

The destruction of York was the first of many acts by the American army that culminated in the capture of Fort Niagara in December of the same year and the subsequent burning of American towns along the Niagara River including Buffalo, New York. The stolen wig was paraded among American troops as a scalp, presented by the savage Native tribes the British had chosen to ally themselves with, and further signs of their uncivilized nature. The mace would return to Canada in 1936 by then US President F.D. Rosevelt and remains on display at the Provincial Legislature. The Lion remains at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis. The actions of the British and Sheaffe in their quick retreat gained Sheaffe ill repute among many Canadians especially Reverand Strachan, which would lead to the promotion of the militia myth, following the war’s end. That myth being that it was ordinary Canadians, not the British, that saved Canada.

Modified Anniversary Speed Graphic – Kodak Ektar f:7.7 203mm (Yellow-15) – Kodak Plus-X Pan (PXP) – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:00 @ 20C

Today there are still some markings of the conflict, the most obvious being Fort York, having been rebuilt through 1814 and 1815 and remains Canada’s largest collection of buildings from the War. The former site of the old Parliament buildings is today a Nissan dealership at Front St E and Parliament St. The American landing site remains unmarked but is at the intersection of Lakeshore and Dowling. A set of lions and a plaque sit in front of the Liberty Grand Entertainment Complex on Lakeshore. And of course, the best place to learn about Toronto during the War is at the Fort York Historic Site which is open year round.

Written with files from:

Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812 Second Edition by Gilbert Collins – 2006 The Dundurn Group Publishers

Web: www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_york_1813.html

Hickey, Donald R. Don’t Give up the Ship!: Myths of the War of 1812. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2006. Print.

Berton, Pierre. Flames across the Border, 1813-1814. Markham, Ont.: Penguin, 1988. Print.