This entry I’m writing specifically for my dear friend Erin, who like me, has a love for the War of 1812. In one of her recent blog posts, she mentioned her new job at an independent children’s book publisher, Pajama Press. The book, Acts of Courage, covers the story of Laura Secord. My entry today is not on Mrs. Secord, but rather the British officer she interacted with, James FitzGibbon. FitzGibbon, not one of the first heroes of the war that one would think about, his contributions overshadowed by Laura Secord and Issac Brock. Fitzgibbon’s story blends with them both. An Irishman raised from the ranks that went on to serve Upper Canada twice in his career in the army.

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm 1:2.8G

FitzGibbon was born in November of 1780 in Glin, Ireland. His family was not wealthy, and at fifteen James joined the local Yeomanry, after three years of service he transferred to the Tarbert Infantry Fencibles, a home service regiment in Ireland. During his time in the Fencibles, he decided to join the regular army, the 49th Regiment of Foot. During his European Service with the 49th, he fought in the battles of Egmond aan Zee and Copenhagen. It was in 1802, FitzGibbon, now a Sergeant along with the 49th and their commander Isaac Brock were sent to Upper Canada. Brock took the young man under his wing, teaching him how to be a gentleman, and in 1806 secured an ensign’s commission for FitzGibbon, in his Regiment, the 49th. It was rare in the 19th century to have an officer raised from the ranks, and often was detrimental to the man in questions, but FitzGibbon seemed to slide into the role with ease, and by 1809 was promoted to Lieutenant.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 10:00 @ 20C

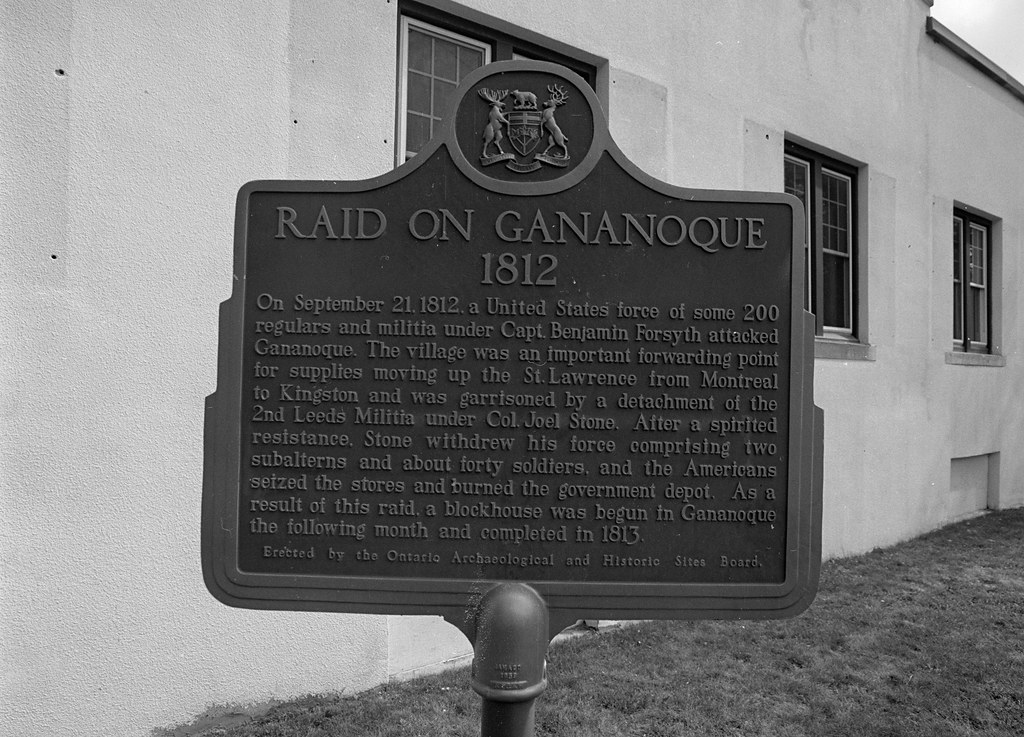

Even early in the War of 1812, the Lieutenant managed to catch the eye of both the men and officers. Under the noses of the Americans managed to escort supply boats along the St. Lawrence River, and then again managed to keep the supply lines clear through the winter of 1813, bringing much-needed supplies from Montreal to Kingston. Just before the Battle of Stoney Creek in June of 1813, FitzGibbon managed to infiltrate the American Camp, disguising himself as a farmer he peddled butter to the American soldiers to listen in on camp gossip. Using his intelligence, the British Forces, with FitzGibbon participating as a company commander, managed to drive off a greater number of American soldiers.

Graflex Crown Graphic – Schneider-Krueznack Symmar-S 1:5.6/210 – Kodak Plus-X Pan (PXP) – Kodak Microdol-X (Stock) 8:00 @ 20C

Following the action, FitzGibbon saw a need for irregular warfare in and received permission to raise a volunteer force of fifty men from the 49th to form an elite force of guerrilla soldiers to harass American forces in the Niagara Peninsula. Today we would call the irregular force Commandos, but the Americans called them Bloody Boys. They would use gray coats to cover up their usual red-coats to provide better cover. But it was on June 22nd, 1813, that FitzGibbon saw the crowning victory of his career. After a journey of 20 miles through occupied territory, Laura Secord, a resident of Queenston, brought news of on an American attack, designed to take out the thorn in their side, Lt. FitzGibbon. Secord brought news that five hundred American troops were heading towards DeCew house, his headquarters. FitzGibbon, his men, and several native allies took to the field. With the native Allies harassing the American column, FitzGibbon showed up, and under a flag of truce, informed the Americans that they were outnumbered, and surrounded. The Americans surrendered, and FitzGibbon was made a hero, promoted to Captain and transferred to the Glengarry Light Infantry. FitzGibbon would remain a captain for the rest of the war, participating in the Battle of Lundy’s Lane and the bloody siege of Fort Erie in 1814. FitzGibbon was the first British officer to return to Fort Erie following the American retreat in November of the same year.

After the Treaty was signed ending the war, James FitzGibbon remained in Upper Canada serving in the Incorporated Militia, and in 1826 was promoted to full Colonel. He also worked for the Adjutant-General of the Militia, becoming the assistance to the Adjutant-General, and in 1827 was appointed as clerk to the Upper House of the Assembly. He was known for his ability to break up rants by House members, a skill that was put to use to break up a riot in 1832 outside William Lyon Mackenzie’s printing house. FitzGibbon, still a Colonel in the Militia played a role in the 1837 rebellions, trying to convince Lt. Governor Head to take action against the rebels, Head eventually conceded that the militia should be called out, and appointed FitzGibbon acting Adjunct-General of the Militia. FitzGibbon, in the act of defiance against Head, posted units on Yonge Street, which allowed them to easily intercept the Rebels that were marching from the north and managed to disperse them. After the rebellion had ended, FitzGibbon resigned in protest because of his treatment by Head. After the death of his wife in 1847, he returned to England, becoming a Military Knight at Windsor Castle until his death in 1863, and is buried there.

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm 1:2.8G

Sources:

www.herontrips.com/Fitz.html

Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812 Second Edition, Revised and Updated

Gilbert Collins