If there is a single fort in Ontario that I would choose to hide out in during a Zombie uprising, that fort is located in Prescott, Ontario. Fort Wellington, named for Sir Arthur Wellesly, following his victory at Talavera on 27 June 1809. Unlike many forts in Ontario, Wellington never saw a direct attack during its entire history; the garrison proved an excellent defensive post along the venerable supply line of the St. Lawerence River. The village of Prescott, established in 1810 as a stopping point for the main road from Montreal heading west to the main urban centres of Kingston and York (Toronto). And it’s placement near a series of rapids on the river made the village an excellent point to offload from larger ships and onto smaller bateaux that could navigate the rapids before being loaded onto lake ships at Kingston.

Nikon FM2n – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.8 – Fuji Neopan Acros 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

Royal Engineers established a large military reserve east of the village proper and, in 1813, following the first year of the war, began construction of a simple fortification. The fort followed a simple square design with an offset gatehouse. The walls were simple earthworks with enclosed and reinforced castmates that acted as magazines for the fort’s ammunition and powder supply. A two-story wooden blockhouse provided a secondary defensive structure for the garrison troops at the centre. Additional troops would live in tents inside the fort’s walls. Atop the walls, a pair of artillery placements housed a pair of 24-pound guns that could fire against any enemy ships on the river. On the American side of the river, the community of Ogdensburg was protected only by small artillery batteries and were no match for the British fortification. The fort’s presence maintained a level of peace in the area as both countries relied on the river for supplies. That didn’t leave the garrison out of the war; twice in 1813, troops from Fort Wellington would participate in major engagements and several smaller skirmishes. Troops would first, in February 1813, march across the river in retaliation for American rifle regiment raids against Brockville and smaller settlements. The Battle of Ogdensburg ensured an unofficial understanding between the residents. The larger Battle of Crysler’s Farm would take place in November that year further east near Morrisburg and mark the final major invasion of the St. Lawerence River Valley during the conflict. The fort provided the main base for a locally raised regiment, the Glengarry Regiment of Fencible Light Infantry, during the war. These green jacketed skirmishers would serve across Upper Canada during the war.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Ektar 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Ektar 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

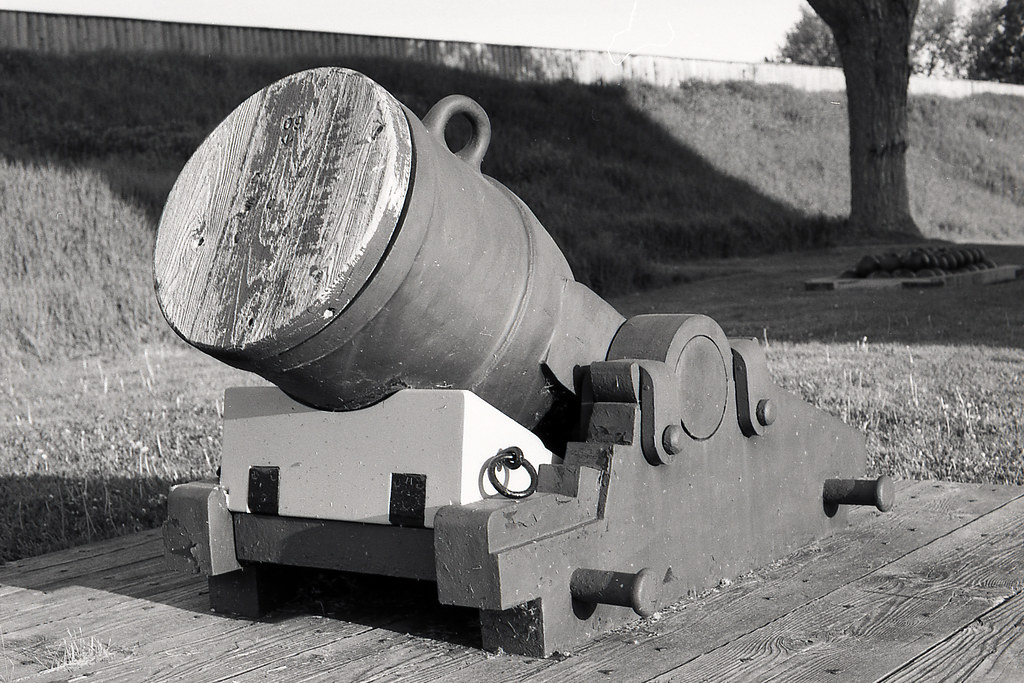

At the end of the war, the fort would slowly fall into disuse; the Treaty of Gent and the Rush-Baggot Agreement of 1818 ensured a level of peace and security along the St. Lawerence River. The British army, however, maintained a presence until 1833. And despite abandoning the post, they never released ownership. The walls and castmates collapsed during this time, and the wooden blockhouse fell into disrepair. The fort’s abandonment was short-lived; political turmoil in Upper Canada spilt over into civil unrest. In 1836, a group of rebels under William Lyon MacKenzie launched an attempt to overthrow British rule and form a new republic. While MacKenzie’s attempts would fail, many Americans would join the cause. The British Army began to re-establish several of its former forts in response. Among them, Fort Wellington. The earthworks were increased in width and lowered slightly in height, the two 24-Pound canons were reinstalled, an additional two 12-pound guns were installed and pointed inland, and a 32-pound carronade was installed over a new stone gate. A pair of 14″ mortars were installed to fire on any river-based attacks. A new rifle gallery or Caponier was established to provide excellent small-arms fire. A three-storey stone blockhouse at the fort’s centre provided additional defence and housing for the garrison. The garrison was made up of a new locally raised unit, the Royal Canadian Rifle Corps. While the fort was never attacked directly during the Upper Canada Rebellion, the rebels did plan to capture the fort and use it as a base for further operations. The attack failed, and the rebels were routed further west at what is known as the Battle the Windmill was among the final engagements of the rebellion. Although by the time the fort was completed in 1839, most of the fighting had ended.

Nikon FM2n – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.8 – Fuji Neopan Acros 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

Nikon FM2n – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.8 – Fuji Neopan Acros 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

The British maintained an armed presence at Fort Wellington until 1863 when it was turned over to the Canadian Militia and several other former British military posts across Canada. During its service under the Canadian Militia, it continued to act as an armed post, mainly used for Training but garrison troops during the Fenian Raids of 1866. But it spent much of the latter part of the 19th century as a training centre or storage facility. When Canada entered World War One in 1914, Fort Wellington again sprang to life. It became a staging depot for troops travelling between Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal as Prescott was home to a terminus and railyard for the Canadian Pacific Railway. The CPR line from Ottawa terminated here and joined the CPR mainline making the fort an ideal spot to recruit, transport, and house troops. Many troops would continue further east and board troopships heading for Europe.

Nikon FM2n – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.8 – Fuji Neopan Acros 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

Nikon FM2n – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.8 – Fuji Neopan Acros 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

On 30 January 1920, Fort Wellington gained National Historic Site status, and three years later declared surplus property by the Department of the Militia. The former fort, now pushing 100 years old, was transferred to Parks Canada (Dominion Parks Branch in ’23). Under Parks Canada, significant repair and archaeological work were conducted on the original fortification. The post’s latrine provides a goldmine of details through the refuse. The latrine provided a unique look at the daily life of the post from the 1840s through the early 20th century. During the 1930s, several buildings were reconstructed or demolished and not replaced, and the site was transformed into a museum.

Nikon FM2n – AI Nikkor 135mm 1:2.8 – Agfa Precisa 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

Nikon FM2n – AI Nikkor 135mm 1:2.8 – Agfa Precisa 100 @ ASA-100 – Processing By: Old School Photo Lab

Today Fort Wellington is shown how it would have been during the post-rebellion era. The site is home to a comprehensive collection of original and reproduction buildings, although the original walls, blockhouse, and artillery pieces. The 24-Pound canons are dated to the War of 1812. Site staff are dressed in period-appropriate garb, with the guard dressed in the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment uniform. The blockhouse houses a museum that displays the entire site history. Located east of the fort is the Battle of the Windmill Site, which is also worth visiting.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Sources:

Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812 Second Edition, Revised and Updated

Gilbert Collins