The Battle of Stoney Creek is recognized by many as one of the engagements that saved Upper Canada. And they would be right, by the end of May 1813 the British Army having been defeated at the Battle of Fort George retreated from the Niagara frontier and established a new defensive post at Burlington Heights, fortifying a small farm that commanded a view of Burlington Bay. A network of Blockhouses and earthworks to hopefully hold any further American aggression before they could reach further into Upper Canada.

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

The American Commander, General Henry Dearborn was a cautious commander. Rather than follow the recommendations of his more fiery commanders he chose to consolidate and secure his beachhead at the former British Garrison at Fort George. But in early June he was ready to make his move, deploying two divisions under General William H. Winder and General John Chandler. By the 4th of June, the two Generals had made camp at the Gage Farm, their headquarters in the Gage Farmhouse, today a part of Stoney Creek, Ontario. Their combined divisions numbering 3,400 troops. Both Winder and Chandler were hoping to have the element of surprise on their side as they approached the army of General Vincent at Burlington Heights. What they didn’t count on was a released prisoner of war.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Rollei RPX 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 7:00 @ 20C

Isaac Corman, a local boy, and cousin of famed American General, William Henry Harrison, and recently released Prisoner of War had been given his parole to return home on the condition he did not share anything regarding the American camp or the sentry password. True to his word he did not tell anyone, save his curious cousin, Billy Green, who after spotting the approaching American armies had made his way to his cousin’s home. Corman, thinking of a way around his promise passed this information along to Green who promptly rode to Burlington Heights to warn the British army there. Vincent, wanting to confirm this information sent the former protege of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, Lieutenant James FitzGibbon to scout out the American position. Using a disguise, FitzGibbon posed as a butter peddler and wandered through the American camp making careful notes of each unit and where they were located.

Pacemaker Crown Graphic – Schneider-Krueznack Symmar-S 1:5.6/210 – Kodak Plus-X Pan @ ASA-125 – Kodak Microdol-X (Stock) 8:00 @ 20C

On the night of the 5th of June, 1813 a small force of 700 troops left Burlington Heights under the command of Colonel John Harvey with General Vincent coming along marched on the Gage Farm under the cover of darkness. With flints removed and silence enforced they were able to dispose of several sentry posts along the way without raising any alarm. It seemed that the darkness was on their side. What they did not realize was the American’s had realized the tactical error in their camp layout and moved the whole camp of the 25th US Infantry back. When Harvey’s troops burst from the woods, they found only cooking fires and started camp followers. With the alarm raised, the Americans were quick to react to the surprise attack. The two sides began to engage blindly in the early morning light. Harvey knew that he was easily outnumbered but encouraged his troops to keep fighting. Despite many attempts, the British could not break through, and when the American artillery on the high ground opened fire, it would take a miracle to turn this fight around.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 (400TX) @ ASA-320 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. E 9:30 @ 20C

The miracle would come in the form of a pair of tactical blunders by Chandler and Winder. Fearing the collapse of their flank, the 5th US Infantry were moved away from the center; this critical error exposed the artillery. The gap was large enough for the 49th to charge. With a shout, Major Plenderleath lead his men up the hill chasing off or killing the American gunners. Despite this, the battle soon turned into a furball; the American generals were taken prisoners after thinking themselves among friendly troops. General Vincent fearing all was lost rode off in a hurry getting himself lost in the woods. Command of the shattered remains of the American army fell to a single Dragoon officer who charged his men in, on what he thought were British troops and smashed into the remains of an American infantry regiment. Both sides quickly retreated fearing the other would soon rally.

Sony a6000 – SMC Pentax A 1:4 200mm

The Americans would fall back to Forty Mile Creek, where despite reinforcements would again be forced back by a combined attack by British Army and Naval Elements a few days later. General Vincent would be found the next day when the British occupied the Gage Farm. The general managed to lose his hat, sword, and coat for some reason that he never revealed. The Battle of Stoney Creek would stand as the furthest into Upper Canada any American Army would march during the war. While the importance of the battle would be shadowed by the engagements later that year at Chrystler’s Farm and Chateauguay, it would stand as one of the key battles that preserved Upper Canada from total occupation and mark the turning point of the American offensive of 1813.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 (CPol) – Kodak Tri-X 400 (400TX) @ ASA-320 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. E 9:30 @ 20C

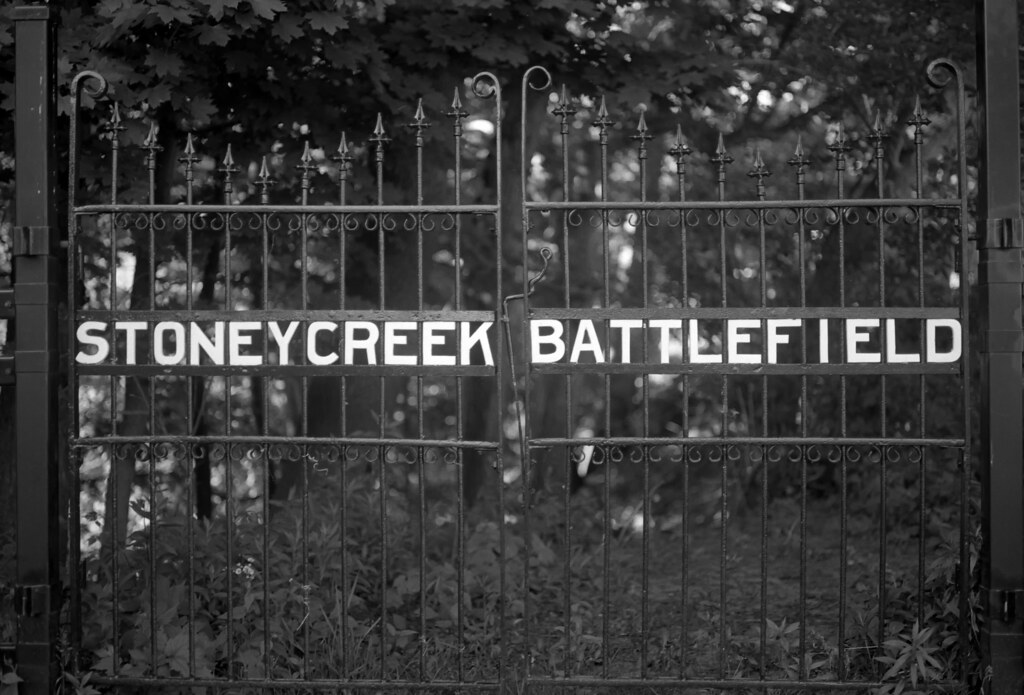

Today the site of the original battle is pretty much lost, a modern parking lot and medical clinic occupy the site. But there are several small 19th-Century monuments that mark the site of the American artillery battery and a grave to commemorate the American soldiers that died during the battle as well as the British. The Gage Farmhouse is open to the public and sits in the shadow of the much larger 1913 monument that was opened on the 100th Anniversary of the Battle. Today the site is known as Battlefield House and hosts an annual reenactment, one of the oldest War of 1812 reenactments in North America, on the first weekend of June.

With Files from:

Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812 Second Edition by Gilbert Collins – 2006 The Dundurn Group Publishers

Collins, Gilbert. Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print

Hickey, Donald R. Don’t Give up the Ship!: Myths of the War of 1812. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2006. Print.

Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1989. Print.

Elliott, James, and Nicko Elliott. Strange Fatality: The Battle of Stoney Creek, 1813. Montréal: Robin Brass Studio, 2009. Print.