While one of the least known engagements during the War of 1812, the siege of Prarie du Chien, was part of the drama that happened during the entire span of the war and sealed British dominance in the northwest until the signing of the Treaty of Gent that ended the way. The battle was the only one fought on the soil of what would become the state of Wisconsin. Two hundred years ago the small fur trading post of Prarie du Chien was a part of the Illinois Territory. Founded by the French in the late 1600s, turned over to British control following the French-Indian War of the mid-1700s and became a part of the new United States of America until the Treaty of Paris in 1783. While officially the post and the small population of fewer than one hundred people were American citizens the post was British in all but name, and the population was mostly French.

The Mississippi River as it stands today near the battlesite

Intrepid – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 (Orange) – Kodak TMax 100 – FA-1027 (1+14) 9:30 @ 20C

But the United States did see the value in the small settlement, but the start of the War of 1812 saw their energies focused elsewhere. But when William Clark (of Lewis & Clark Fame) became governor of the Missouri Territory in 1813 he started to see a problem with a very pro-British settlement to his north. Should the British decide to enforce their influence at Prarie du Chien there would be little to stop them from sailing south on the Mississippi and capturing St. Louis and gaining an even bigger foothold. Governor Clark became annoyed as the far-flung outpost received little support from Washington. Using his authority he spoke with two local leaders, Fredrick Yeizer and John Sullivan both captains in the local militia. Together they raised a volunteer force of 150 men on a sixty-day enlistment. The volunteer army gained strength by the arrival of 61 men of the 7th US Infantry under the command of Brevet Major Zachary Taylor (who would become President of the United States). Though destined for Fort Clark, Governor Clark presented his case, and Major Taylor agreed to head north to establish a garrison at Prarie du Chien. Three gunboats would provide transport north. Just as the expedition was to start, Taylor was recalled to Kentucky to attend a family member who was ill, in his place Lieutenant Joseph Perkins, who was in St. Louis recruiting for the 24th US Infantry was installed as the commander of the regulars. The expedition departed St. Louis on the 1st of May, with Governor Clark joining them a few days up-river. The flotilla saw minor action along the route but landed without resistance by early June. Using a local warehouse of the Mackinac Trading Company, Clark realized they would have to work fast as his volunteer force was already half-way through their enlistment period. Soon a wooden palisade fort with a pair of blockhouses rose on a mound to the north of the village proper. Governor Clark named the post, Fort Shelby, after Governor Isaac Shelby, the governor of his native territory of Kentucky. With the post’s construction well in hand, Governor Clark returned to St. Louis with much fanfare upon his return. But in the North Perkins realized that if he didn’t have the post done soon, he would lose a majority of his force. But by the 19th, the post was nearly complete.

A reconstruction of a blockhouse that would have stood over Fort Shelby and later the first Fort Crawford.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Photographer’s Formulary Developer 23 (stock) 6:00 @ 20C

The local population was not too pleased with the arrival of the Americans and three days later two men showed up at Mackinac Island with news for the commandant of the post, Lieutenant-Colonel Robert McDouall. McDouall was disturbed at the news of the American garrison and was even more troubled with natives brought rumors of violence against their tribes at the hands of the Americans at Prarie du Chien. These rumors reached McDouall as the native allies cried out for revenge. The main reason that McDouall was concerned was for the extensive fur trade network, and without Prarie du Chien it would be difficult to maintain the supply lines. McDouall had his problems with a limited force and word of an American attack against Mackinac, but he could not ignore his allies. Giving local militia captain a field promotion to Lieutenant-Colonel, William McKay, would take a force from his unit, the Michigan Fencibles along with local traders that formed a group called the Mississippi Volunteers, a single 3-pound field gun with a Royal Artillery crew was attached to McKay’s force as well. The local tribes provided warriors from the Sioux and Winnebago tribes commanded by two captains from the British Indian Department Thomas Anderson and Joseph Rolette. Departing on the 28th of June, McKay would gather more militia and native troops at Green Bay. When McKay’s force landed at Prarie du Chien on the 17th of July it numbered 650 troops. For Perkins he only saw his numbers drop as a majority of his volunteer force left with Captain Sullivan, Captain Yeizer was willing to stay with forty volunteers to man the gunboat Governor Clark. But the sudden arrival of McKay gave the American garrison a start when Captain Anderson approached Lieutenant Perkins, who was out on a ride with the order of surrender. The garrison refused the surrender order promising to fight to the last man.

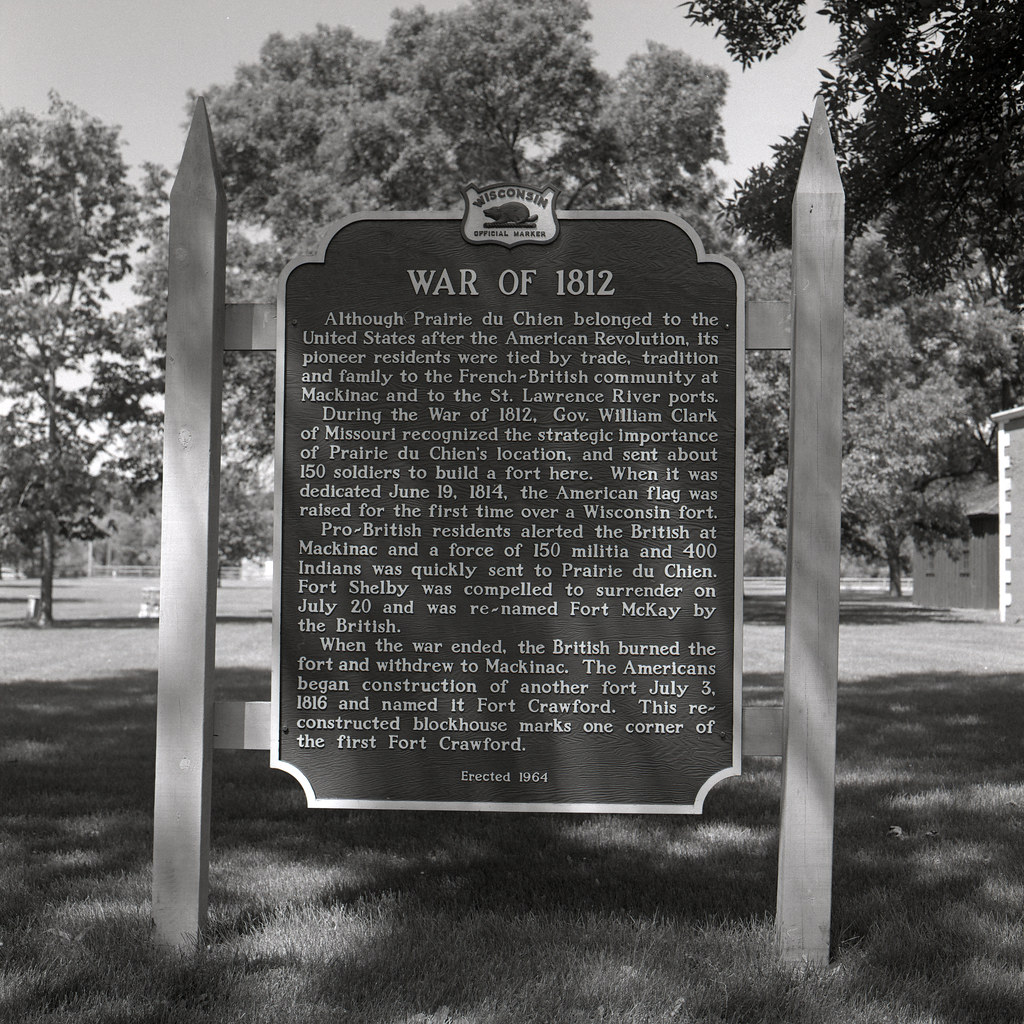

The historic plaque on site outlining the battle.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Photographer’s Formulary Developer 23 (stock) 6:00 @ 20C

McKay realizing that his biggest threat was the gunboat on the river ordered his lone artillery piece to fire on it first. The Royal Artillery crew worked fast, moving the gun around to give the crew aboard the gunboat the impression they were under attack by multiple guns and after a few hours had taken massive damage. Rather than risk the boat and the crew Captain Yeizer cut his moorings and headed south. The fort’s garrison watched in dismay, trying to call them back, as most of their supplies and ammunition were aboard the gunboat still. Both sides managed to fight to a stalemate, with both McKay and Perkins running low on ammunition, McKay going as far as to collect the American round shots and fire them back, of course, neither side realized this of the other. Inside the fort was another story, the well had run dry, and in an attempt to deepen it, the whole thing had collapsed. And while McKay was preparing heated shots to set Fort Shelby on fire, Lieutenant Perkins raises the white flag of truce, after two days of solid resistance. Both Perkins and McKay agree to delay a formal surrender for fear of retaliation against the Americans by the native warriors in light of the rumors. McKay would use his Michigan Fencibles to guard both the American prisoners and the native troops before the formal surrender the next day and then has the Americans escorted down-river without any incident. With a British flag flying over the fort, now named Fort McKay the northwest was firmly in British hands. The Americans would twice send a force to attempt to retake Prarie du Chien both would be stopped first at the Rock Island Rapids and again at the Battle of Credit Island. The British maintained the post at Prairie du Chien throughout the remainder of the war, destroying it in 1815 when they marched out to conform to the terms of the Treaty of Gent.

Probably not the original well from the battle, but I figured it would be good to have a photo of one anyways.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Photographer’s Formulary Developer 23 (stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Today you can still visit the site of the battle, and while the town has moved over to the mainland, the battle site is open to the public as part of the Historic Villa Louis, a historic home built in the 1840s after the American Army abandoned the site completely for a mainland fort in 1832. But visitors can see the footings from the 1816 American fort (Fort Crawford) and a rebuilt blockhouse. The site also hosts a reenactment of the siege in July.

A special thanks to the volunteers at Villa Louis for helping me out and letting me freely wander the site for photographic purposes.

Written with files from:

Berton, Pierre. Flames across the Border, 1813-1814. Markham, Ont.: Penguin, 1988. Print.

Ferguson, Gillum. Illinois in the War of 1812. Champaign, IL.: University of Illinois Press, 2012. Print.

Collins, Gilbert. Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print.

Web: villalouis.wisconsinhistory.org/About/History.aspx