When it comes to photographing sites connected with the naval actions of the war, it can be complicated. Most of the actions take place out on open water, and many don’t have much to photograph especially in the way of ships as many are long gone. Only one ship from the era exists in its original form while another is a rebuild of the historic ship. But if you know where to look there is plenty of things to photograph when it comes to the capture of the Chesapeake. By the summer of 1813, the spirits of the Royal Navy on the North American station was sinking as were their ships. They had lost all of their last major actions off the coast to the US Navy. But one man, Captain Philip Broke aimed to change the luck of his mighty Royal Navy. And he would at a fateful meeting on the 1st of June, 1813.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

The US Frigate Chesapeake (50) was not exactly a favored ship in the American Navy and many sailors and officers in the service considered her unlucky. The Chesapeake, of course, is the same ship that was at the center of the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair in 1807 that nearly lead to war and was a critical factor in the American declaration of war in 1812. The frigate’s cruise in the spring of 1813 had met with some success it left her captain, Samuel Evans in a bad health, to preserve himself and the sight in his one remaining good eye, he requested relief of his command. When she sailed into Boston Harbor, the matter of the crew also came to a head. For many the arrival in Boston marked the end of their enlistments and the ones who were left were disgruntled over the matter of their share of the prize money. Even Captain James Lawrence, freshly promoted off his successful capture and destruction of the HM Brig Peacock (18). Lawrence was none too keen on taking command of the Chesapeake hoping instead for the famous US Frigate Constitution (52). But the letter from the Secretary of the Navy was not a request but an order. Lawrence’s first order was to pay out the prize money to the crew; the second was to bring over able-bodied seamen from the Constitution to bring his numbers up.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 – Blazinal 1+25 6:00 @ 20C

The HM Frigate Shannon (52) was a different ship entirely. The crew had been working together as a unit since before the start of the war. Her captain, Philip Broke, had gone to great lengths in ensuring that his crew remains intact even going as far as burning prize vessels. Broke prided himself on the fine art of naval gunnery. Using his funds, he equipped the Shannon’s guns with sights and the use of powder and ammunition for live gunnery practice, gun crews who hit their targets would be rewarded. The practice of live gun practice was largely abandoned by the Royal Navy following the Battle of Trafalgar, but the number of ship-to-ship actions on the North American station caused the Admiralty in London to reinstate the practice on the North American station. Broke also would present the crew with hypothetical situations to the crew and ask how they would go about defending the ship as well as plenty of practice with small arms. The one disadvantage that Broke had was that his ship had been on patrol for fifty-six days.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

For Broke it wasn’t just his honor at stake but that of the whole Royal Navy. He sat just off Boston Harbor waiting for a chance to engage an American ship. The US Frigate President (55) had managed to slip past in the fog making it out to open water. The Constitution would be laid up for months. Only the Chesapeake remained, and Broke was of the mind that Lawrence would remain in the safety of the harbor until the Shannon’s supplies had run out. So Broke decided to force an action, penning a challenge directly to Lawrence to a ship-to-ship duel, under any condition that Lawrence wished, sending a paroled prisoner to deliver the challenge directly to Captain Lawrence, a challenge that never reached the captain. Lawrence had no intention of waiting out the Royal Navy. To inspire the crew on 1 June 1813 under full sail and flying three American flags as well as Lawrence’s personal battle flag, a white ensign emblazoned with the phrase “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights” a matter both important to Lawrence and the Chesapeake. All the messenger could do is watch as the frigate sailed out.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

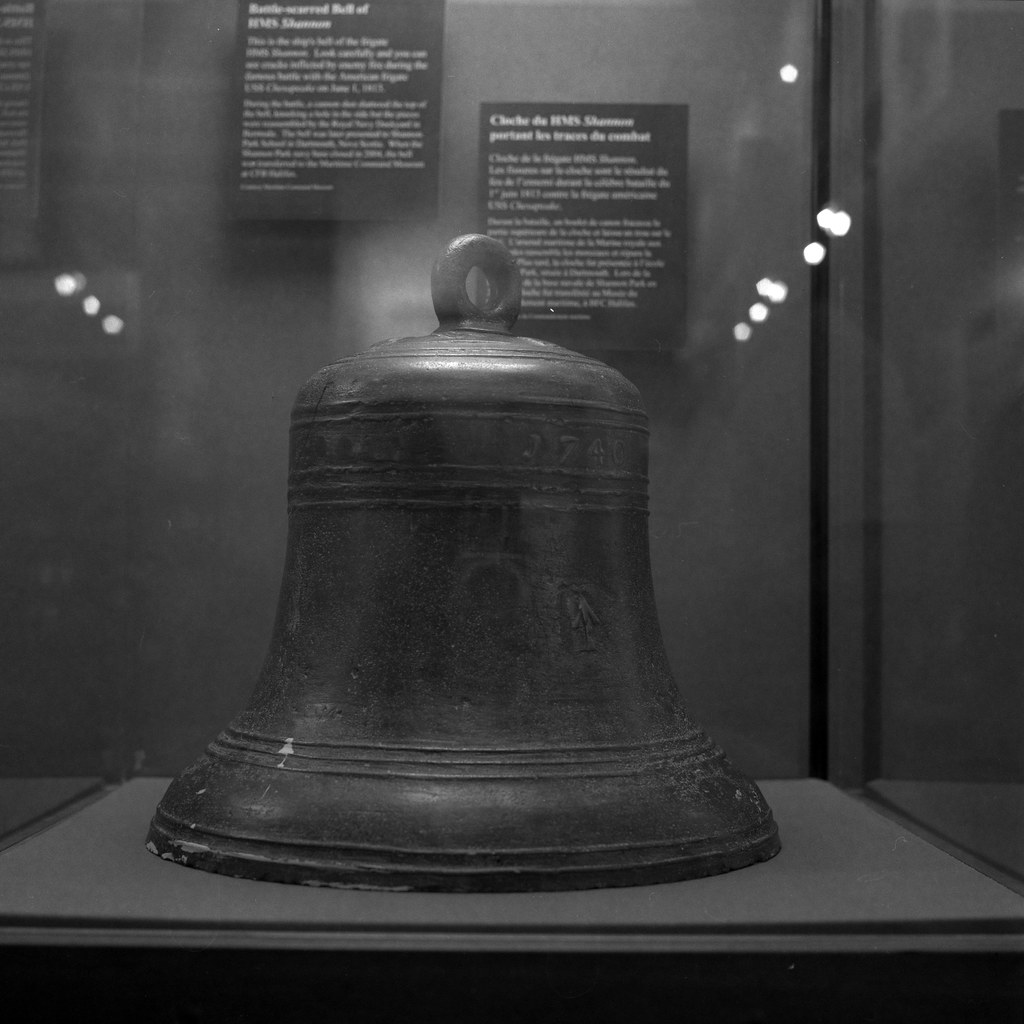

The two ships were almost of the equal match in size, guns, and men. So when the two ships met, thirty-seven kilometers off the Boston light between Cape Anne and Cape Cod the two ships spotted each other. A sailor aboard the Shannon was taken by the three flags flying from the American frigate he requested to Broke if they (as in the Shannon) could have three ensigns as well. Broke just replied that they had always been an unassuming ship. And to the Americans, the Shannon would be an easy target as the long patrol had left the ship weather worn and shabby. The two ships took little time bearing down on the other and Lawrence, despite having the weather in his favor, refused to rake fire across the bow of the Shannon. Broke spoke to his gun crews; he didn’t want to destroy the enemy frigate; he wanted it as a prize. Don’t throw away a shot; he warned, their aim wasn’t to de-mast the ship but to kill the crew. It was the Shannon who scored the first hit sending iron though the forward gun decks were shattering both ship and crew. As the Chesapeake was moving faster, the British gun crews worked in deadly fashion firing shot-after-shot as the enemy sailed past. Despite the havoc being caused, Lawrence’s men responded in kind. While they suffered, as many American ships did, with poor powder, the underpowered shot would hit the water or bounce off the Shannon. But some hits were scored, taking out some of the enemy 12-pounders as well as damaging the rigging. Lawrence, realizing that if he kept up the speed, he would soon pass the British ship and ordered a short turn into the wind, a maneuver known as a pilot’s luff, to cut his speed. As the Chesapeake started her turn, her quarter deck was exposed to fire from the Shannon’s guns mounted on her quarter deck. Officer and crew fell to deadly fire; the helmsman perished as the ship’s wheel was shot away. In response, the Chesapeake, shot away the ship’s bell as well as destroying the bow chasers in the forecastle along with three crewmen. But with no way to maneuver the Chesapeake found herself trapped against the Shannon.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Both captains made the call for boarding parties. Lawrence was the only officer remaining above decks and the bugler he had requested to sound the call for boarding parties had hidden himself away out of fear. Soon even Lawrence fell, shot by a British sharp-shooter. Coming from below decks to answer the call, Lieutenant Cox found the captain wounded. As the wounded captain went below to the ship’s surgeon his order to the crew was “Don’t Give Up the Ship!” By comparison, the British were well organized, Broke taking the lead charged across to the enemy ship with the first party. The main decks by this point were deserted, most of the officers and the crew had taken refuge below deck. A pair of lieutenants took up the charge and poured out onto the main deck of the ship, nearly forcing the British back. It was the timely arrival of fresh men from the Shannon that saw the tide turn. Upon the tops, British and American sharpshooters had been exchanging sniper fire both with each other and the men below. A royal marine took a small party across the rigging and stormed the American tops killing the men there. A timely gust of wind separated the two ships, leaving Broke a small party of fifty sailors and Marines. While the numbers were not in his favor, most the Americans had given up. The only source of resistance was from the forecastle. Three sailors would jump Broke, the captain killing one before the second knocked him to the deck, a blow from the third opened up Broke’s head. Seeing their captain fall the remaining British stormed the forecastle, bayonetting the sailor before he could make the killing blow. With most of the Americans trapped below, a single shot echoed out killing a Marine. As the angered British began to fire indiscriminately into the trapped Sailors, a quick thinking officer prevented the massacre by threating death on the next man who fired a shot. The action had, according to the official report, taken a short fifteen minutes resulting in seventy-one dead, and one hundred and fifty-five wounded between the two ships. The Shannon quickly organized a prize crew, locking up the Americans in their restrants and keeping the rest at bay by pointing a pair of 18-pound cannon loaded with grapeshot at them through holes cut through the deck. The two ships sailed into Halifax harbor with much fanfare on the 6th of June, 1813.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-200 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 8:30 @ 20C

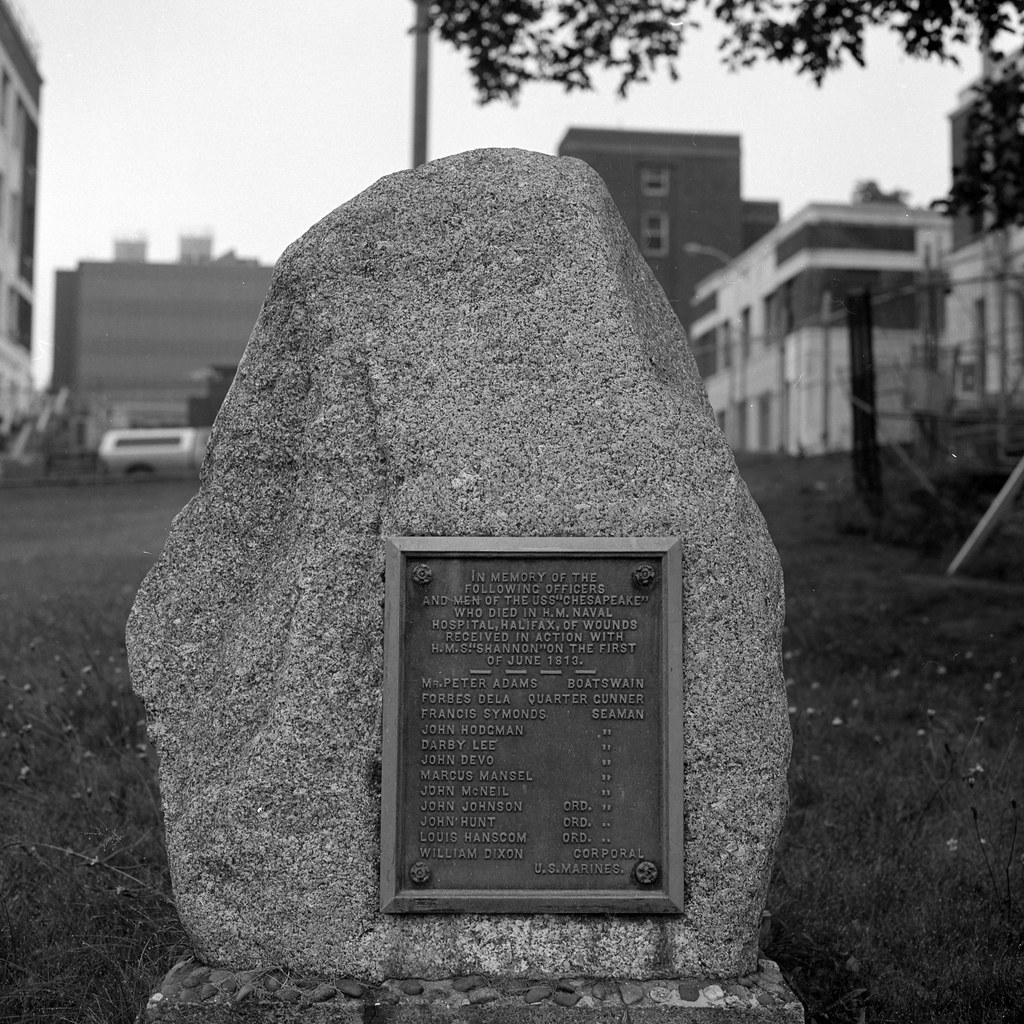

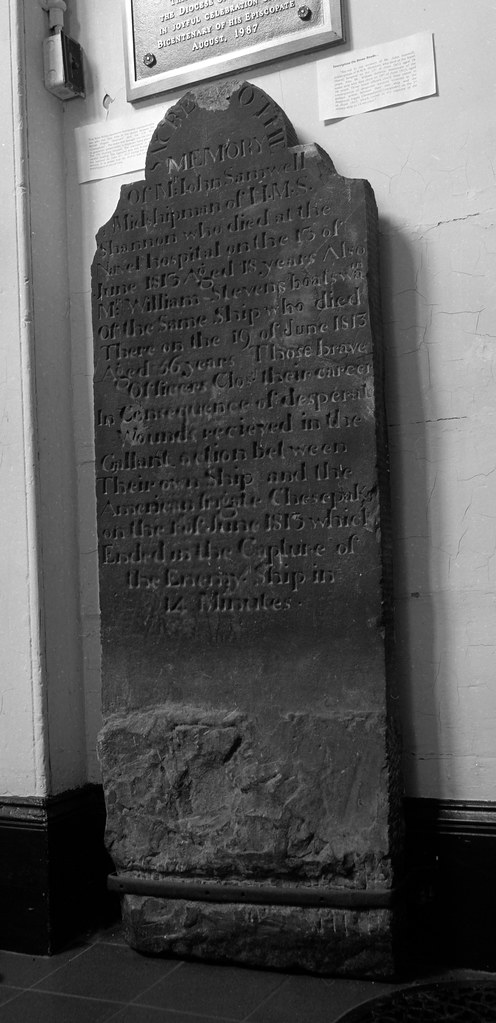

Captain James Lawrence would pass away on the 4th of June, 1813, complaining the whole way over the fact that the crew had surrendered. He was laid to rest with full honors at HM Dockyard Halifax (his body would later be moved to the Trinity Church Cemetary in New York City). The dead from both crews were laid to rest at the dockyard as well. The American prisoners were transferred to Dartmoor Prison in Portsmouth, England aboard the repaired HM Frigate Chesapeake (50). Captain Philip Broke would be named a hero and carried the title “Broke of the Shannon” but he would never command again, his head wound plaguing him the rest of his days. Lieutenant Provo Wallis would command the Shannon on her journey back to Halifax and earn a promotion to Commander and would eventually become Admiral of the Fleet and the longest serving member of the Royal Navy a record still held today. The Chesapeake despite the change in flag would retain her bad luck and was sold for timber in 1819; the Shannon would continue to serve until 1859 until she was broken up. Despite this, there is still plenty to see here in Canada from the Action.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

The Shannon’s Bell and pieces from the Chesapeake were saved by the Royal Navy and ended up in the collection of the Naval Museum of Halifax and are currently on loan to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. A gun from each ship was also saved and now sit outside Province House in Halifax, Nova Scotia, although when I was there, they had been removed for restoration. The dead from both ships still lay in the old Royal Navy Burying Ground on Canadian Forces Base Halifax (Stadacona), if you ask nicely you may even be allowed to visit. The timbers from the Chesapeake were turned into a mill that still stands in Wickham, England. And the sister ship of the Shannon the HM Frigate Trincomalee (52) is restored as a museum ship in Hartlepool, England. The capture is also represented in two pieces of fiction, Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers discussing the court martial of Lieutenant Cox and in Patrick O’Brien’s The Fortune of War, where Captain Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin are present on the Shannon during the action as Captain Aubrey is cousin to Captain Broke.

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Special Thanks to Richard Sanderson, Director of the Naval Museum of Halifax and the men and women of CFB Halifax for assistance in writing this piece and granting me permission to photograph on the base. As well as Melissa Bellefeuille for showing me the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

Written with Files from:

Hickey, Donald R. Don’t Give up the Ship!: Myths of the War of 1812. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2006. Print.

Pullen, H. F. The Shannon and the Chesapeake. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1970. Print.

Lossing, Benson John. The Pictorial Field-book of the War of 1812 Volume 2. Gretna, LA: Pelican Pub., 2003. Print.

Web: www.eighteentwelve.ca/?q=eng/Topic/24

Web: www.1812privateers.org/NAVAL/shannon.html

Web: museum.novascotia.ca/resources/nova-scotia-and-war-1812/hms-shannon-and-uss-chesapeake