During the British invasion and subsequent occupation of what is today eastern Maine, there were several forts involved in the action. While many have unique histories, there isn’t much to give each one their blog entry. So I’ve decided, for the sake of you readers, to combine them all into a single post. In the interests of geography, I’ll be moving from east to west if you want to follow along with the route on a map.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

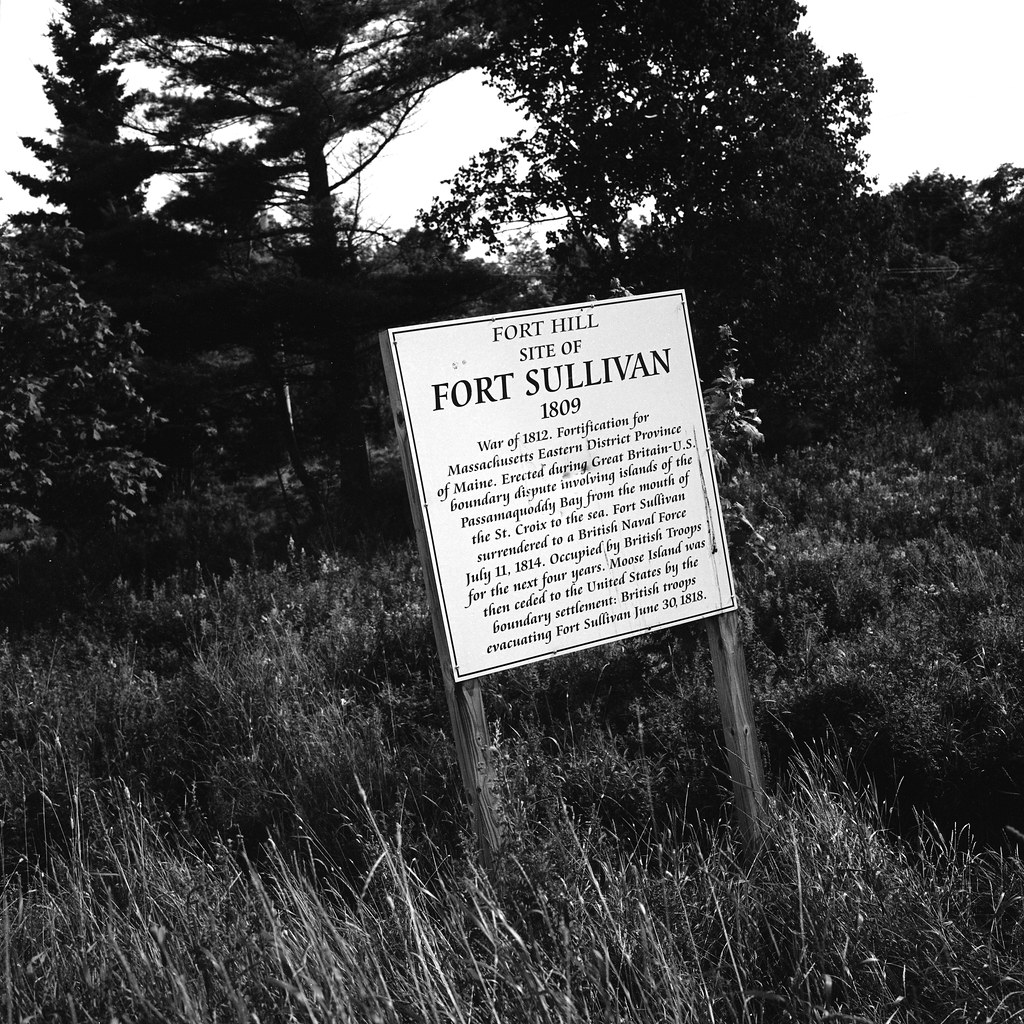

Even before the war started, the contest over Moose Island remained a sticking point in Anglo-American relations from the American Revolution. The island’s only main village Eastport, Maine, near the New Brunswick/Maine border. Fearing British encroachment, the US Army established Fort Sullivan in 1808. A single four gun circular battery with a powder magazine, blockhouse, and barracks. The island remained in the care of Major Perley Putnam and a small garrison of men from the 40th US Infantry. When the British showed up in the fall of 1814, Major Putnam surrendered without a fight. The British renamed the fort after the governor of Nova Scotia, John Coape Sherbrooke and left 800 regulars to prevent any American attempt at retaking the fort. When the war ended with the Treaty of Gent in 1815, the issue with the border remained unsettled, even though the treaty stipulated that every return to how it was before the war, the border wasn’t settled before the war. As a result, Moose Island and Fort Sherbrooke remained in British hands until 1818, when the American army returned the fort reverted to Fort Sullivan, and the garrison would stay at the fort until 1873. The post remained intact until 1880 when the locals began to remove items for constructing other town buildings, today there is little left. A sign marks the location of the fort and a cannon from the war now sits in front of Shead High School, that sits next to the fort site. The powder magazine should still be there; I was unable to locate the ruins. The only real part of the fort that remains standing today is the 1808 barracks, a wooden frame building that now houses the town’s museum and Historical Society and is located on Washington Street.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Next along the route is Fort O’Brien in the Town of Machiasport, Maine. One of the oldest forts on the list, the post, was built in 1775 as Fort Machias by two officers in the Continental Army, Captain Jeremiah O’Brien, and Major Benjamin Foster. Established in response to a possible attack following the capture by American forces of the HM Schooner Margaretta. The British attack was swift and in 1777 chased off the defenders, but the British did not stick around, and the fort was reoccupied by 1781 under the name Fort O’Brien. With the end of the Revolution, the fort was abandoned and fell into disrepair. When border disputes in the early 19th century threatened to boil over the old post was rebuilt a stone and earth bastion mounted four guns. The fort never saw action during the British invasion of 1814 but was the final American post that was destroyed by the British after they had established the occupation. The British simply took the guns and demolished the position rather than commit the troops to occupy it. The American army would rebuild the post for the third time during the American Civil War mounting three 32-pound cannons along with a pair of rifled 24-pound guns. Due to the position the fort never saw action and was abandoned in 1865. Today a single brass Napoleon gun from the civil war is mounted on the earthworks; the powder magazine is still there as an overgrown mound. The site is designated a state park and sits behind Fort O’Brien School.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

A fascinating fort on my journey was Fort George in Castine, Maine as it has the richest history of all the forts. Established in 1779 as the primary British post in the colony of New Ireland. Major General Francis McLean would hold out against a great American Siege in the later days of the American Revolutionary War. Fort George is also the largest fort visited, sitting on a ridge above the village of Castine, with a clear view of the Penobscot River. The American force of 45 ships and 200 infantry failed to dislodge General McLean and were compelled to flee upriver and burn their ships. The debacle known as the Penobscot Expedition would be a low point during the Revolution. One of my favourite authors, Bernard Cornwall, wrote a wonderful novel The Fort about the failed American expedition and is well worth the read or listen. The massive earthen walls would remain above the town, and when General Sherbrooke arrived in 1814, he would order the post rebuilt when he reestablished New Ireland. The 200 square-foot Fort would mount some 60 guns, and the British surrounded the town with a ring of smaller forts and artillery batteries. When the war ended the garrison marched out in 1815 with much fanfare from the townsfolk. The American Army would occupy the old British fort until 1819 when Fort Knox was completed further up the river. Today you can still see the massive earth walls as well as the ruins of a casemate and powder magazine. A small marker in one of the bastion identifies the site, and a lone cannon from the British occupation is just by the parking lot. The interior of the fort has a baseball diamond.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

The final fort that I visited was Fort Madison, also located in Castine, Maine. Established in 1808 during the border tensions between the United States and British North America the simple earthen bastion mounted four 24-pound cannons, a blockhouse, and brick magazine. It would be the only fort to engage the British during the invasion in the fall of 1814, the garrison commander; Lieutenant Andrew Lewis would fire a single volley from the heavy guns before beating a retreat. The British would operate the post as Fort Castine during the occupation. At the end of the war, the British destroyed Fort Castine along with the rest of their fortifications when they retreated in 1815. The American army would operate the post until 1819 before moving all operations north to Fort Knox. During the American Civil War, the site was rebuilt and manned by local volunteer troops who operated the site, calling it Fort United States. The Civil War-era earthworks still stand, and the site is a city park, an 1812 era cannon is located at the site as well.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

While not much to look at, in reality, none of them having anything beyond some old cannons, earthworks, and maybe an information sign they still make up a strange and relatively unknown part of the War of 1812 and themselves weaved into the fabric of the tale. I do highly recommend visiting at least Castine, Maine as they have a thriving historical society that loves to share their town’s history with any who are interested.

Special Thanks to the Castine Historical Society for helping me on my journey and providing additional information and location details!

Written with Files From:

Collins, Gilbert. Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print.

Young, George F. W. The British Capture & Occupation of Downeast Maine, 1814-1815/1818. Print.

Web: castine.me.us/welcome/history/history-of-castine/