One of the most iconic and controversial campaigns of the Anglo-American War of 1812 are the British operations in the Chesapeake Bay region of the United States during the late summer and fall of 1814. This action was a true invasion; it was an attempt to force the US to sue for peace but on British terms, but it was more than that, it was revenge. It was the action that took the war to President Madison doorstep.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 (TMX) @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+25) 6:00 @ 20C

Just as the war in North America started because of the war in Europe, so to the invasion of the American east coast was linked to the end of that war. Napoleon had in October 1813, lost the Battle of Leipzig and as a result, the allied nations had chased the French Emporer back to Paris and by the spring of 1814 Napoleon had abdicated ending the War of the Sixth Coalition. With Napoleon established as the king of the small island nation of Elba, Great Britain could turn their attention to the War in North America. Since March of 1813, the Royal Navy had established a blockade on the eastern seaboard and squadrons were raiding all along the coastline with little respect for American property. By 1814 several thousand British regular troops were beginning to arrive in the Canadas. A majority of these forces were put under General George Prevost’s command at Quebec City to affect an invasion of upstate New York which ultimately ended in disaster at the Battle of Plattsburg. A second group arrived in Halifax and under the command of General John Sherbrook successfully invaded what is today eastern Maine holding it under British control. The third and finally group acted on their own under one of Field Marshall Arthur Wellesley’s ( Lord Wellington) top commander, Major General Robert Ross. Ross’s army was attached to a squadron of 24 warships under Rear Admiral George Cockburn and consisted of 4,500 British Regulars. And these weren’t colonial troops; these men were battle-hardened in the fields of Europe. When word of Napoleon’s defeat reached Washington DC, the American capital, the government was not too concerned. Both the President and Secretary of War, John Armstrong, did not think that the British would attack the capital city. Washington DC offered little of strategic value; Armstrong was sure that the British would attack the larger port city of Baltimore and ordered that General Samuel Smith increases the defenses around the harbour city. Armstrong did create the 10th Military District to defend Washington DC but offered little help or support to the District’s commander, General William H Winder.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 (TMX) @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+25) 6:00 @ 20C

Winder and Armstrong did not see eye-to-eye. Armstrong would go out of his way to show his annoyance to Winder’s appointment to the district command, even blocking his attempts to call up the militia. Armstrong felt that the militia could be called up quickly to surprise any potential British invasion or attack. While Winder did inspect the region, he did little to shore up the defenses around the capital, either through his lack of desire, or lack of support from the government. The British, on the other hand, were in a much better position. Cockburn having been raiding along the coast for the better part of a year had a strong knowledge of the region and had even captured Tangier Island, a small island just outside of the Chesapeake Bay off the coast of Virginia. The island was to act as a staging ground for the British forces. Cockburn wished to launch a direct assault on Washington DC; Ross urged caution. He did not feel comfortable attacking without cavalry and artillery support, and there was the question of the small American naval force under Commodore Joshua Barney and his Chesapeake Bay Flotilla. The flotilla was the only thing keeping the British out of the bay, giving Winder a bit more time, and even though he could outnumber the British, at least on paper, he was commanding a mostly militia army that was both under trained and under equipped.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 (TMX) @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+25) 6:00 @ 20C

While the two British commanders worked well together, they still had not agreed on a target, but they did agree it was time to make a move on the American mainland. Cockburn would take a small number of ships with his flagship, HM Frigate Menelaus (38) in the lead headed for Baltimore to throw off the Americans while another group of bomb and rocket ships made a successful raid against Alexandria, Virginia. Ross landed his troops on the 19th of August at Benedict, Maryland and began his march north. By the time he reached Nottingham, it was enough to scare Commodore Barney. Barney would order the flotilla scuttled and his men marched towards Bladensburg. At Bladensburg, Winder had ordered Brigadier General Tobias Stansbury to establish a defensive line at Bladensburg while he took a body of troops to occupy Long Old Fields (today the town is known as Forestville, Maryland). Winder was hoping to stop the British at Upper Malborough. Winder’s army engaged the British vanguard on the 22nd and gave Winder pause enough to pull back as Ross occupied Upper Malborough. From there, the British could strike at either Baltimore or Washington DC. At Bladensburg, Stansbury had established a strong defensive line controlling all roads leading into and out of the village and held the high ground. By the 23rd Ross had been convinced to attack Washington DC at the urging of Cockburn and the personal plea from General Prevost to avenge the wanton destruction of the village of Port Dover. Ross had two routes to choose from, if they went south, they would need to find a way to ford the Anacostia River or head north through Bladensburg which had a bridge across the river. On the 24th Ross first headed south then swung north. Winder though in a strong position to attack the British opted to retreat across the river destroying the bridge in the process out of fear of a night assault.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 (TMX) @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+25) 6:00 @ 20C

At Bladensburg, news reached General Stansbury that Winder had abandoned Long Old Fields and the British were on the move. Stansbury, despite holding a strong position retreated across the river leaving the Bridge intact and reorganizing the men into three defensive lines. At Washington, it became apparent that the British were moving towards the capital and in a rush began to remove as much as they could from the government buildings in a mass exodus. Ross would be facing close to 5,000 American troops at Bladensburg, but only 1,000 of them were regulars a mix of US Infantry, US Dragoons, US Navy Sailors, and Marines. The remainder local Virginia and Maryland militia units supported by Artillery. Ross, on the other hand, had a mix of veteran troops from the Royal Marines, 4th, 21st, 44th, and 85th Regiments supported by Royal Marine Artillery and Rocket troops. As the British took the field, it became painfully clear that Stansbury in retreat across the river had been a tactical error. Had the American general stood his ground he would have made the British pay for every advance and engage them in dirty street fighting in the village. Ross’s officers would mock the appearance of the farmer’s army that they now faced across the river.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 (TMX) @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+25) 6:00 @ 20C

Seeing the bridge intact, Colonel William Thorton of the 85th Regiment along with other light troops took the lead and made to cross the bridge. The American artillery on the opposite bank did little to stop them. The light troops in skirmish order, spread out rather than tightly packed lines, made it difficult to hit them with solid round shot and the Americans lacked canister shot. Thorton’s steady advanced forced the American gunners and militia into a retreat. Winder upon seeing this made an attempt to drive off Thorton’s light brigade, only to have his flank turned by the 44th that had forded the river. With the reinforcements Thorton’s brigade pushed in against the American’s second line only to be repulsed, Thorton himself wounded in action. The 44th moved up and drove back the line. Winder in a panic ordered a general retreat. The militia fled in terror, and the word did not reach Barney and his sailors and Marines entrenched on a hill that made up the third and final line. Barney’s men held on the longest, taking the combined effort of the 4th and 44th to break through. The battle had turned into a route and Winder lost complete control over his men. The British would mock them calling it the Bladensburg Races as the militia fled towards Washington.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 (TMX) @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+25) 6:00 @ 20C

The city already in general panic was not comforted by the sight of their militia fleeing in the streets. The action had cost the British, with 64 dead and 185 wounded. Many troops simply collapsed under the summer heat. The Americans counted only ten dead, four wounded, but the British had taken over 100 prisoners. They also carried off the field some American artillery pieces and the colours of two units, the 1st Hartford Light Dragoons, and the James City Light Infantry. Ross would wait, knowing that there was no way the Americans could secure the way to the capital. Washington was almost a ghost town, only a handful of people remained, most of the government had fled to Maryland or Virginia in the face of possible capture or death.

Pacemaker Crown Graphic – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 – Adox CHS100II @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+25) 5:00 @ 20C

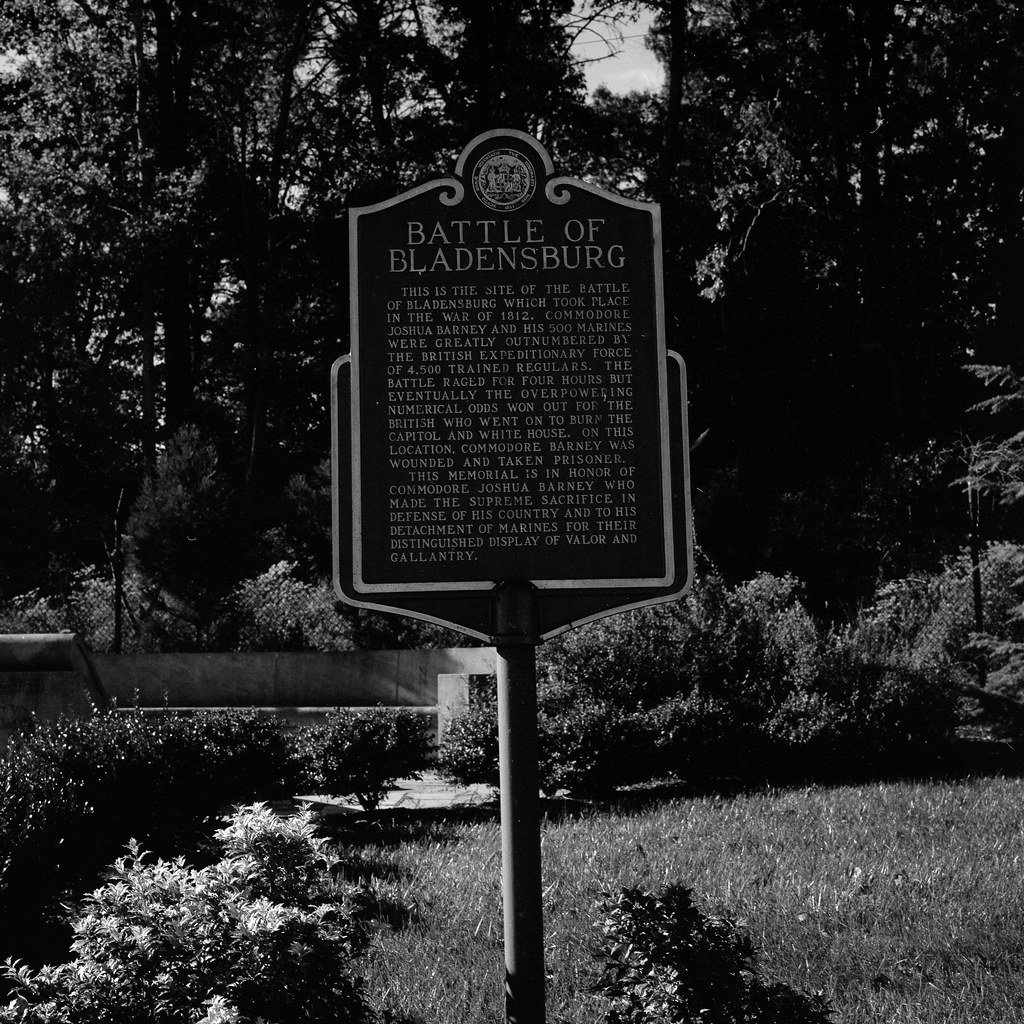

Like many battlefields from the War of 1812, there is not much left of Bladensburg. The expansion and urbanization of the area have rendered the field all but covered up. The old Bladensburg Bridge although sketched by Lossing in the mid-19th century was replaced in the 20th-Century by the new US-1 bridge that now spans the river. The Bladensburg Waterfront Park has a visitor’s centre relating to the battle that featured artifacts from the battle on display.

Written with Files from:

Collins, Gilbert. Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print

Hickey, Donald R. Don’t Give up the Ship!: Myths of the War of 1812. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2006. Print.

Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1989. Print.

Lossing, Benson John. The Pictorial Field-book of the War of 1812 Volume 2. Gretna, LA: Pelican Pub., 2003. Print.

Berton, Pierre. Flames across the Border, 1813-1814. Markham, Ont.: Penguin, 1988. Print.

McCavitt, John, and Christopher T. George. The Man Who Captured Washington: Major General Robert Ross and the War of 1812. Norman: U of Oklahoma, 2016. Print.