In photography’s history, critical technologies reshaped photography, from the earliest processes with plates and harsh chemicals to flexible films, interchangeable lenses, and folders to SLRs. One of the most significant changes is the introduction of microprocessors into cameras. This led to the creation of affordable cameras with auto-exposure functionality and the right ecosystem for creating autofocus cameras. While Minolta did not invent autofocus, they were the first to get an entire ground-up autofocus system SLR with a new look and feel compared to previous SLRs to market and meet with commercial success. The 7000 AF is a camera born of the era. While still a functional camera, it does pale compared to the cameras that came with constant improvements spurred forward by the 7000 and the pioneering spirit of all the other camera manufacturers who jumped on the AF bandwagon.

Camera Specifications

Manufacturer: Minolta

Model: Maxxum 7000

Alternate Names: α-7000, 7000 AF

Type: Single Lens Reflex

Format: 135 (35mm), 24x36mm

Lens: Interchangable, Minolta A-Mount

Shutter: Focal Plane Shutter, 30s – 1/2000s + Bulb

Meter: Centre Weighted TTL SPD, EV -1 ~ EV20 @ ASA-100, ASA-25 – ASA-6400

Autofocus: TTL Phase Detection, EV2 ~ EV19 @ ASA-100

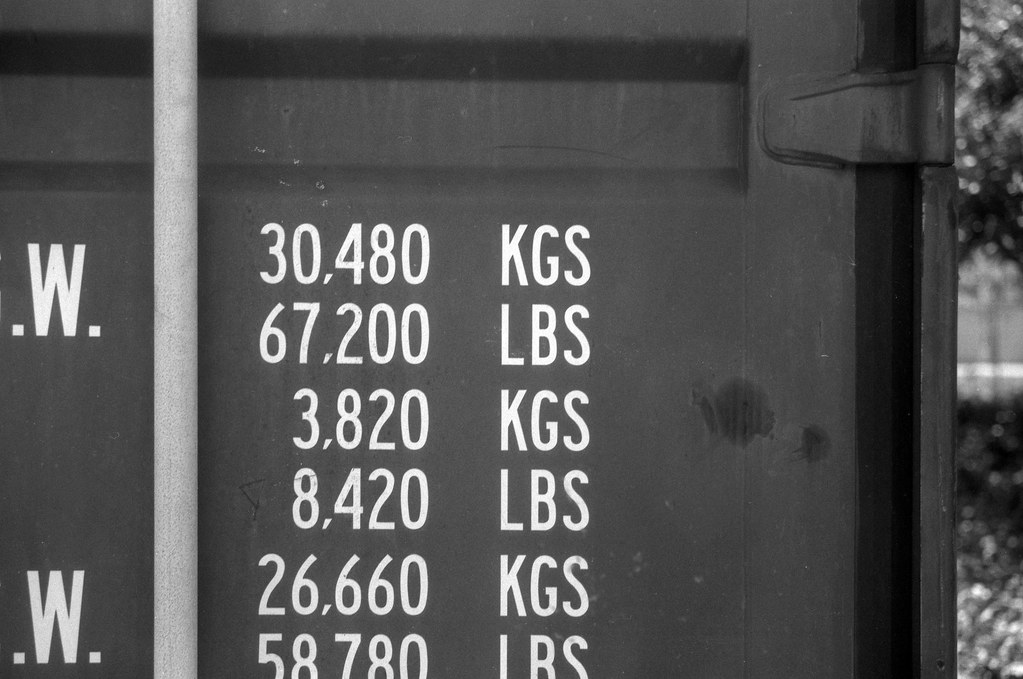

Dimensions (WxHxD): 143x92x60mm

Weight: 601g w/o lens or batteries

Power Source: 4x AAA Batteries

Year of Manufacture: 1985-1988

Background

Minolta’s corporate history started in 1929, initially producing cameras in Japan using German lenses and shutters. Based solely on either roll film or plate formats, the name “Minolta” was used as a trade name for cameras starting in 1933 or 1934, depending on who you ask. The use of 35mm film began after the Second World War. SLRs started to be produced in 1958, with the SR-2 being the first camera using the SR-Mount for lenses. The SR-7, released in 1962, featured a body-mounted CdS coupled exposure meter. Four years later, an open aperture TTL meter-equipped SLR, the SR-T 101, hit the market. The 1970s brought some exciting changes to Minolta, notably the technology-sharing agreement with Copal and Leitz to coordinate and share camera and optics technology for the betterment of all three. The agreement brought about the X-Series of cameras. While Minolta had been working on the X-1 in the previous decade, it wasn’t until 1973 that the X-1 first hit the market. The X-1 was rapidly followed by several SLRs built using shared technology. The first was the XE, known as the XE-7 in North America. It featured Minolta’s first integrated auto-exposure system using the SR-Mount, allowing photographers to set the aperture, and the camera would select the shutter speed or Aperture Priority metering. The XD followed the XE a few years later, introducing aperture and shutter priority auto-exposure modes. The X-Series also featured more consumer oriented SLRs, the XG line that offered up more automation. But the real jewel of this era is 1981s X-700, the first Minolta SLR to feature full auto-exposure or program mode.

Believe it or not, the development of autofocus technologies started in the 1960s in almost parallel development in North American Honeywell and Europe, Leitz. Yes, Leitz, the company famous for sticking to manual focus even well into the autofocus era. Interestingly enough, Honeywell and Leitz were working on the same basic principle for measuring distance using the coincidence rangefinder. The idea is to use a set of lenses, mirrors, and prisms to align two images to determine the distance. While easy to do with an eye, the electronic method was still elusive. Leitz patients for an autofocus system started to be filed in the mid-1960s, but the introduction of charged coupled devices or CCDs in 1969 helped get the ball rolling on a working prototype. Nikon hit the market first with a dedicated autofocus lens in 1971; designed around the F-Mount, this 80mm f/2.8 six-pound monster contained the focusing system and motor system so that it could be mounted on any F-Mount camera. Leitz would demonstrate a camera-based autofocus system at 1976’s Photokina, using a heavily modified Leicaflex SL2, which had been rebranded the CK-2 using their Correfot autofocus system. The prototype CK-2 proved a monster of a camera with the entire CCD/LED autofocus system mounted externally to the camera with a motor to adjust the lens focus. But Honeywell’s Visitronic system arrived in 1977, licensed for use in Konica’s C35AF point-and-shoot camera. Oddly enough, if you look at the Honeywell and Leitz systems, both worked similarly despite being developed separately. Leitz would take another stab at an autofocus SLR in 1978 with a modified Leicaflex R4. While far more streamlined than the original Correfot, it still required six AA batteries and was not integral to the camera. In the end, Leitz would sell the entire system to Minolta, who had started to take an interest in developing an autofocus SLR after Nikon, Canon, Ricoh and Pentax all started autofocus developments.

With the autofocus system out of the way, Minolta could focus on developing the camera body itself. While companies like Canon, Nikon, and Pentax used their existing lens mounts, Minolta’s SR-Mount would be a limiting factor. It also helped that Minolta’s chief of research & development, Icharo Yoshima, insisted that the new autofocus system would be brand new from the ground up. The engineers took the basic three-lug bayonet system and specs of the SR-Mount and made the new A-Mount slightly bigger to include electronic contacts. Yoshima also insisted they could not release one camera and one lens; it had to be a complete system. To help keep the cost of these new lenses low, the focusing motor would be placed in the camera body with a mechanical link to drive the focusing helical in the lens. While manual focus was still possible, the lens design indicated that the camera was natively an autofocus system with manual focusing only as a last resort. Also gone were any physical controls; all things were done through menus, screens and buttons. The Maxxum 7000 hit the market in 1985 with great fanfare. The original price for the camera in 1985 was 329 USD with the 50mm f/1.7 lens or 399.95 USD with the 35-70mm f/4 lens. That’s a cost of 931.66 USD (1251.97 CAD) or 1,132.58 USD (1521.97 CAD) in 2023. Minolta also released a set of twelve lenses ranging from 24mm to 300mm, most being prime lenses and five zoom lenses. Aimed at the advanced consumer market, the 7000 proved an almost instant success. But without controversy, the crossed ‘x’ logo on the North American Maxxum cameras would cause Minolta to get hit with a lawsuit from Exxon. The results forced Minolta to remove the crossed ‘x’ logo from camera bodies and lenses for future iterations. The 7000 was then joined by the consumer-level 5000 and the radically different pro-level 9000 models. Sales of the Maxxum 7000 proved popular enough that after production ended in 1988, a second-generation 7000i replaced the camera.

Impressions

The design of the 7000 is a radical one and is a product of the early 1980s; it looks like some of the first VCRs released: hard angles, lots of screens and buttons everywhere. I can imagine the photographers of the day looking at the 7000 and passing it off as a children’s toy. There aren’t even command dials or buttons with up and down arrows. I can see why Minolta would provide some physical controls to the professional 9000 camera to appease the pro-photographers who were used to that interface style. Even if you’re used to modern cameras, the 7000 will undoubtedly make you think twice. With all that being said, the camera itself isn’t bad-looking; the buttons are well placed, with everything you need in easy reach. The screens provided more than enough information both on the top screen and the one in the viewfinder. But it’s the reliance on these screens and buttons that are also the camera’s biggest weakness. The early LCDs tended to bleed, resulting in information being hidden and making it hard, if not impossible, to use. You also have issues with the membranes behind the buttons degrading and losing the ability to contact the electronic interface on the printed circuits or the buttons breaking. The grips can also crack and break away. On the plus side, the camera does take AAA batteries, making it easy to get replacements anywhere in the world.

Experience

The 7000 is a decent camera in the usability department. Despite the hard lines, it is comfortable in your hand and is lightweight thanks to almost all plastic construction. The one thing I had to get used to was the number of buttons on the camera. Now, as someone who had used either later hybrid cameras or was entirely reliant on physical controls, the 7000 strikes a nice balance. There is not much in the way of menus, so almost every function is tied to buttons on the camera body. The main controls are easily reached, and plenty of information is on the top plate screen and the viewfinder. It is evident from the overall design of the camera and lenses that this is designed for automatic operation, especially regarding focusing. The autofocus on the camera is decent, although it is slow. As a first-generation autofocus, it is okay. The autofocus speed and accuracy are decent when working with slow-moving or stationary subjects. The problem comes when you start to have faster subjects. The 7000 did struggle when I was photographing a War of 1812 reenactment, which may sound slow, but the tactical battles can move quickly. I would rate the speed of the autofocus of the 7000 as the same as the Nikon F4. The metering is decent despite only having a centre-weighted meter, which strikes me as odd given the power of Minolta metering in their older SR-Mount SLRs. In some mixed lighting conditions, the 7000 tended to over-expose. The shutter is okay. There’s some feedback on the shutter release, but it can unintentionally trip if you aren’t careful. Overall, the 7000 is a fun camera to use, and I can see why Minolta went with the mid-level offering first; it offers up enough controls to allow a photographer to grow and learn different styles and techniques quickly and sold the idea of autofocus to the wider photographic community.

Optics

When it comes to optics, what makes the 7000 stand out is that it can take almost every Minolta A-Mount lens produced. The first thing you must watch out for is the modern lenses designed for crop sensor digital bodies or those with SSM technology, a lens-side autofocus motor. The crop sensor lenses will work, but you might run into vignetting at your corners, and the SSM lenses won’t autofocus but will work. And that’s the biggest issue with the Maxxum line: they are dedicated autofocus cameras with manual focus being a secondary thought. That said, there is a tonne of excellent lenses available. The obvious choices are the early generation lenses; they’re stand-up optics, and many are based on the SR-Mount lens formulas or some formulas provided to Minolta by Leitz. The primary kit lens is a good starter lens; 35-70mm f/4 is a stand-up option, or the 50mm f/1.7 if you’re more into prime lenses. These lenses will either come with a camera or can be purchased at an affordable price. You’ll pay more for a crossed-X version, but leave those to the collectors unless you have a crossed-X Maxxum. The “beer can” 70-210mm f/4 matches the 35-70, has excellent optical qualities, and is an affordable telephoto zoom. You can pick up a 28mm f/2.8 from there, and the 100mm f/2.8 MACRO makes for a good three-lens kit. But my choice would be, instead of the 50/1.7, to go for the 50mm f/1.4, which is a sharper lens overall. And if you need that extra reach, the 300mm f/2.8 APO is a legendary lens. But watch out for added front weight; the 7000 is a small body, and some lenses can make the camera front heavy.

The Lowdown

If you’re looking for a camera with historical significance to photographic technology, then the Maxxum 7000 is your choice. They’re getting on in years, so finding someone to repair them is almost impossible, thanks to the amount of electronics in the camera itself. The 7000 is a good camera; it’s an old and first-generation camera so that it could be better. If you are looking at purchasing one, getting one with the crossed-X logo is tempting, but these carry an extra fee. If you want to use the camera, leave those cameras to the collectors and focus on the post-law suit cameras. On the used market, the 7000 is affordable, with almost all examples going for well under 100$. Even with a lens, you can find them for under 50$. But buyers should beware; the cameras may not be in functional shape. In my case, it went up in smoke. But if there’s one thing I take from my time with the 7000, it was a vehicle to get me into the beautiful A-Mount that has yielded two of my favourite SLRs, the Maxxum 9 and 600si Classic!

Further Reading

Don’t just take my word on the Maxxum 7000; you can check out the reviews by other awesome camera reviewers!

Mike Eckman – Minolta Maxxum 7000 Review

Kosmo Foto – Minolta Maxxum 7000 Review

Down the Road – Minolta Maxxum 7000

Silvergrain Classics – Minolta 7000, a Plastic Fantastic Camera that Shocked the World

Ken Rockwell – Minolta Maxxum 7000: World’s First Autofocus SLR

Camera Legend – Minolta Maxxum 7000 Review

Vintage Photo – Minolta Maxxum 7000 Review

Film Photography Hub – The Minolta Maxxum 7000 – An Iconic Camera that drips with 80s Aesthetics

Aperture Preview – Minolta Maxxum 7000

6 Comments