All stories have to start somewhere and to understand everything that happened after the Anglo-American War of 1812 one must learn about how the seeds of the struggles that are to come were first sewn. Pre-Confederation History is a bit of a mess, but there is a single touchstone date where everything stems from, and that is 1791. By 1791, the American Revolution was nearly a decade over, and many who still lived in the former colonies swore loyalty to the British Crown. Many did not wish to remain under a republic, and many Americans did not want these Tories in their country. And in the act of Parliament, the Province of Quebec, that is what remained of New France acquired by Great Britain after the French-Indian War, was split into two provinces, Lower Canada and Upper Canada. For his service during the American Revolution, the Colonial Office appointed John Graves Simcoe as the first Lieutenant-Governor. But that was not all that changed in the colonial system in 1791. The Constitution Act would serve as the basis for all colonial governance. The British Parliament had taken a singular grievance of the American Revolution, No Taxation Without Representation, and twisted it into Imperial Interests to create a new form of government for the individual Provinces of the Empire.

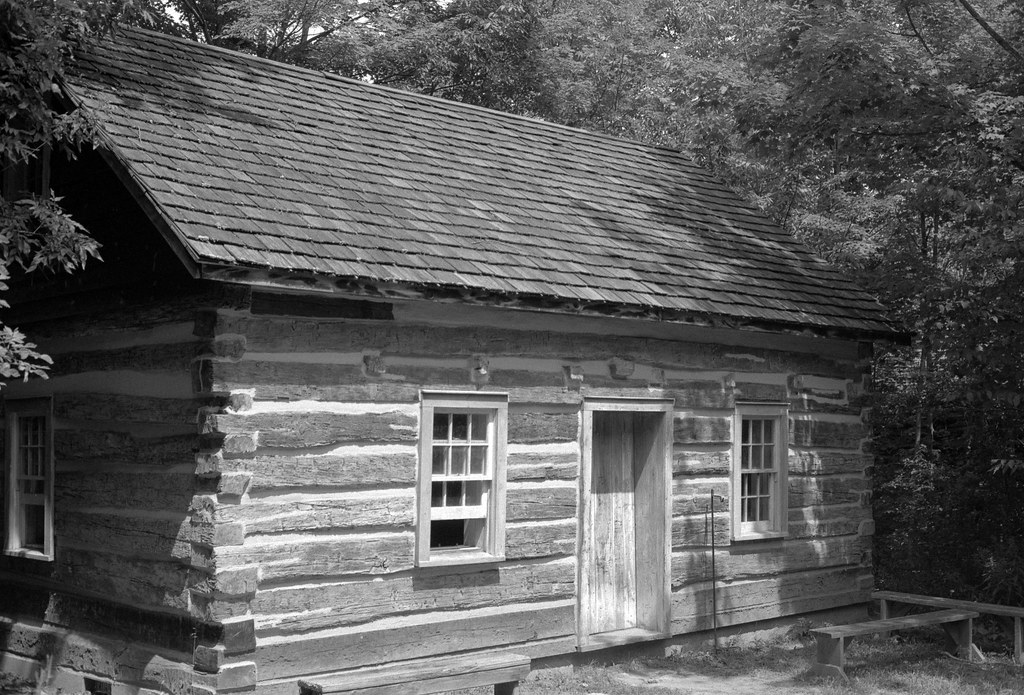

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

The Constitution Act made it appear that autocratic rule that is direct rule by an appointed governor had been replaced with some level of representation. Under the Act, the Governor retained direct control over the Province, and to assist him in ruling he would appoint a small group of men to advise him, this body, known as the Executive Council, had the direct ear of the governor. The Executive could also directly affect how the Province would be run. The next body down would be the Legislative Council, a larger body often with a member representing each district within the Province would be mostly for oversite of the next body down. Much like the Senate today, these members were also appointed or were also members of the Executive Council. The final body within the Parliament was the Legislative Assembly, and it was the only group that saw general election by the civilian population. That is if you were male and owned land you could both run or vote in the elections. Districts had several seats based on population within the Assembly. The Assembly would handle the mundane tasks of the Province, handling schools, infrastructure, and of course collection of taxes. The problem remained is that the Assembly was at the mercy of the two upper bodies and the governor. Any bills passed by the assembly could be vetoed by the Council, Executive, or Governor. These upper bodies could pass laws without consulting the Assembly first. If the assembly did not play well, the Governor could dissolve the body and force elections. The only real power held was the withholding of tax revenue, but even then the governor could pull money from other sources or simple call for new elections. But if everyone was loyal and felt the system worked, there were no real issues of division. The Province, especially Upper Canada, was made up of known loyal families, the United Empire Loyalists. And the entire body, while acting like a real Parliament was not a real Parliament, it got its power from the law, a law passed and held by Parliament in London and the Colonial Office and ultimately the Crown. Any changes passed along from England must be enacted, and if the Governor was not doing a good job, he to could be easily replaced on even a whim. I eluded to one of the biggest issues that came out of the Consitution Act was the slow centralisation of power to a small cadre of men. It all stemmed from vagueness in the language of the Act when it came to cross-appointments. While Sir Guy Carleton, Governor of Lower Canada assured that the Executive and Council remained separate, Simcoe came to a conclusion there were no legal blocks to appointing the same person to both bodies. Simcoe had limited men to work with and wanted to ensure total loyalty. And in the first Parliament, four of the five Executive Members were also members of the Council.

Nikon F5 – AF Nikkor 35mm 1:2D – Adox CMS 20 II @ ASA-20 – Blazinal (1+100) 18:00 @ 20C

The cross appointments ensured a loyal and smooth operation within the Provincial Parliament. It also helped with the passage of a key law in Upper Canada that would also change the course of the Province’s history. In 1793, the invention of the Cotton Gin created a labour issue in the United States. The new Gin streamlined the separation of Cotton Fibres from Cotton Seeds, and with the streamlining there was an increased need for more cotton to be picked. And that job landed on enslaved people, specifically blacks. For them, life, which had already been difficult increased. Pressure to pick more and more each day broke them. And the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, which required escaped slaves to be returned, only made matters worse. Despite Simcoe and several other upper-class members of Upper Canada society owned and used slaves, the passage of the Act to Reduce Slavery in 1796 gave some level of hope. The act remained only local to Upper Canada and did not end slavery in the Province. Rather it made any person who arrived a slave after 1796 would be granted freedom. And any person born into slavery would get their freedom when they turned twenty-five. Any slave who arrived before 1796 would remain a slave until their death. Many in the United States who believed in ending slavery altogether learned of this new law and began to help those who sought freedom escape first to free states and then to Upper Canada. But even for freed slaves life was far from good in Upper Canada, many forced to live in shanty towns outside of the major population centres often taking on menial labour jobs for minimal pay. Life in Upper Canada remained status quo, the vast untamed tracts of land offered those in vast power amounts of wealth. When Simcoe left, future governors would continue to allow the loyalists to rule, and power continued to centralise. And the governors could care less, tax income flowed. And the Colonial Office enjoyed the new world order, they had planned to create a new version of aristocracy for the New World, but with the cadre of men forming their own, the merchant Baron. And the Colonial Office openly supported and made sure all their Governors also encouraged the creation. And the Merchant Barons in return sent their raw materials onto Montreal and England to drive the home economy. Upper Canada remained a rural backwater; roads were little better than tracks through the woods, the few urban centres were little better.

Minolta XE-7 – Minolta MD Rokkor-X 45mm 1:2 – Kodak Panatomic-X @ ASA-32 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. H 9:00 @ 20C

By 1812, Upper Canada’s population had shifted, while Loyalist families still made up the core, immigration had brought several other cultures into the mix, French-Canadian, Irish, Scottish, and even some Americans now occupied the Province. But the power still rested with that initial group of Loyalist who had grown rich and the Governors who allowed the practice to continue. When the United States declared War on Great Britain as part of a wider Napoleonic Conflict in the Summer of 1812, the Governor, Sir Francis Gore, left for England, leaving nominal control to General Isaac Brock. While Brock would not be given the same sweeping powers as a governor, as President of the Executive Council and Commander-In-Chief of the British Army stationed in Upper Canada he had enough power to execute the war. While the vast nature of the Canadas proved a tempting target for invasion, it would be the treatment of American sailors by the Royal Navy that caused the war in the first place. The one thing that the Americans hoped was that Canadians would rise and welcome them as liberators rather than invaders. It would be the same issued that Brock and the Executive feared, thankfully the militia did mobilise on the side of England and were part of Brock’s Army that captured Fort Detroit in the first major action of the war. For his actions Brock earned the title of Saviour of Upper Canada, he also would be made a Knight. Glories and laurels he would not learn about as he would be shot leading a charge to recapture Queenston Heights in October of 1812. It would be Brock’s second-in-command, General Roger Hale Sheaffe, who rallied a force of regulars, Mohawks, and militia retaking the Heights and driving off the American invasion. The colonial elites did not look kindly on the war, the military took control of every commercial aspect of the colony. And while many served as officers in the colonial militia, the Military governors paid little attention to them. The real breaking point would take place during the capture of the Provincial Capital of York, today Toronto, Ontario. The defence of the town proved to be an issue for General Sheaffe, having a small local garrison, a group of Provincial Troops, and the militia was a no-show, having scattered to defend their homes. To make matters worse, an explosion at one of the shore batteries killed and wounded many of Sheaffe’s regulars. Fearing all was lost, Sheaffe ordered the garrison magazine destroyed, and the regulars retreat to Kingston and leaving the militia to negotiate the terms of the surrender, an act that did not sit well with the elites, among them Chief Justice John Beverly Robinson and Reverend John Strachan. The American would go on to capture Newark and was stopped at the Battle of Stoney Creek, and the situation reversed at the Battle of Beaverdams. The war continued in a tit-for-tat manner, with the Americans taking the western reaches after the disastrous defeat at the Battle of the Thames, and in the east, the British won twin victories at Chrystler’s Farm and Chateauguay preventing the Americans from cutting Upper Canada off from Lower Canada. The arrival of General Gordon Drummond marked the return of strong leadership to the British Forces and reinforcements. Justice Robinson got his moment in the limelight when he executed the Bloody Ancaster Assizes against traitors seeking to aid the Americans in the invasion and annexation of Upper Canada, sending seven men to the gallows. And while the Americans again defeated the British in the summer campaign of 1814 taking Fort Erie again, and beating the British at Chippawa, the only open battle of the war. But the British had moved on the American east coast, capturing and holding parts of modern-day Maine, and defeating the Americans and burning Washington, but failed to take Baltimore. But the peace process had already begun the small town of Gent in Belgium. And on Christmas Eve, 1814 the two countries signed a treaty ending the war. And with neither side holding any major sway, the treaty ended the war with honour, and both sides avoided not loosing, but not winning either. The treaty would not prevent the Battle of New Orleans.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Many were not pleased with how the war ended; the British would turn over territory captured, Mackinac Island, Fort Niagara, and Maine. The Americans would return the western reaches. But the war left deep scars and the return of strong anti-american views among the population of Upper Canada. Each side maintained, even expanded their naval squadrons with ships like the HMS St. Lawerence proving British supremacy on the Great Lakes. The post-war era provided a rich environment for the growing power of the colonial elite, who used the actions of the war to continue their efforts to keep Upper Canada, English, Anglican, and a colony of the Empire. And the return of Sir Francis Gore would only aid their cause, as he was more than happy to let the elite have their way because it showed the Colonial Office the loyalty of Upper Canada. But times were changing, and a Scottish reformer had received word that his wife had inherited a plot of land near Queenston, and he booked passage to check the land out.