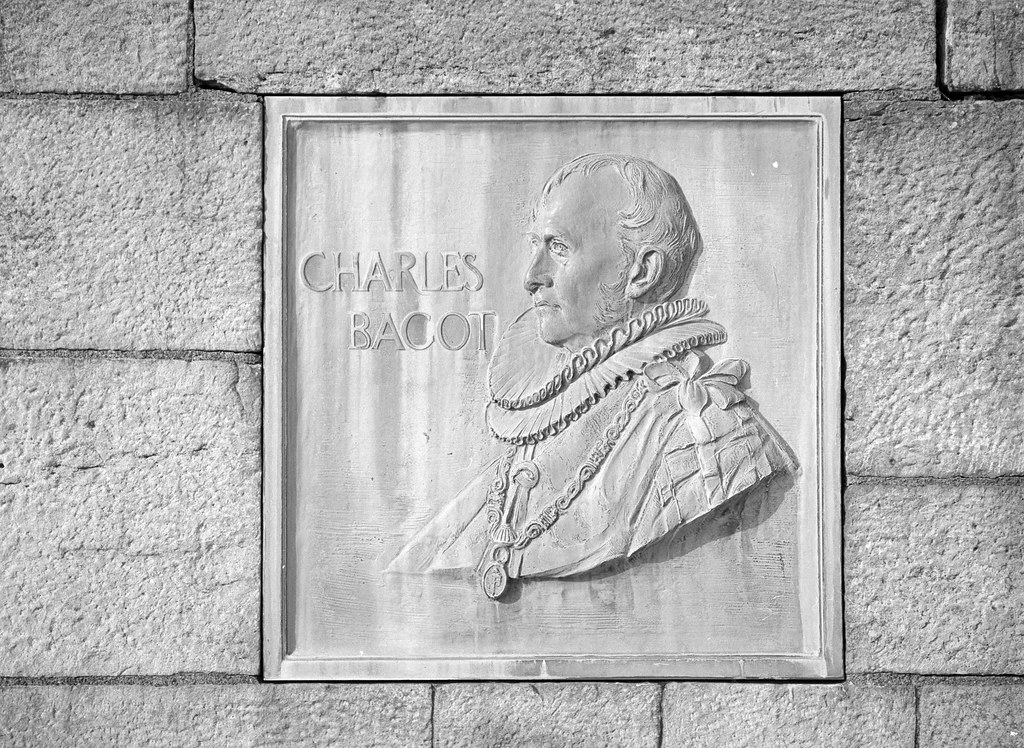

In Post-War British North America, the British authorities took a two-pronged approach to the defences of their North American holdings. The first through a series of upgrades to the defensive forts along the border and the bolstering of the British garrisons, the second would be to prevent another war through a series of negotiated agreements and treaties. The idea would be to shore up the start of better relationships and fill in the gaps left by the Treaty of Gent. If you have read the Treaty of Ghent and understand its context you’ll quickly realise Ghent could not be the final say for normal relations between Great Britain and the United States. The primary purpose of the Treaty of Ghent was to end the War of 1812 and press a giant reset button on the relations between the two countries. And by June of 1815, Charles Baggot arrived in Washington DC as the British Ambassador and John Quincy Adams arrived in London as the Ambassador to the Court of St. James. For Adams, he felt that the mere presence of the Naval Squadrons on the Great Lakes was hampering the resurgence of trade between the nations. Both the United States Navy and Royal Navy were maintaining their naval squadrons and had ships under construction. The largest of them remained the HMS St. Lawerence (104) of the Royal Navy Squadron, but the US Navy had its own ships-of-the-line planned. But the fact remained to maintain the large squadrons cost a lot of money, money both governments did not have as they were coming out of disastrous wars.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

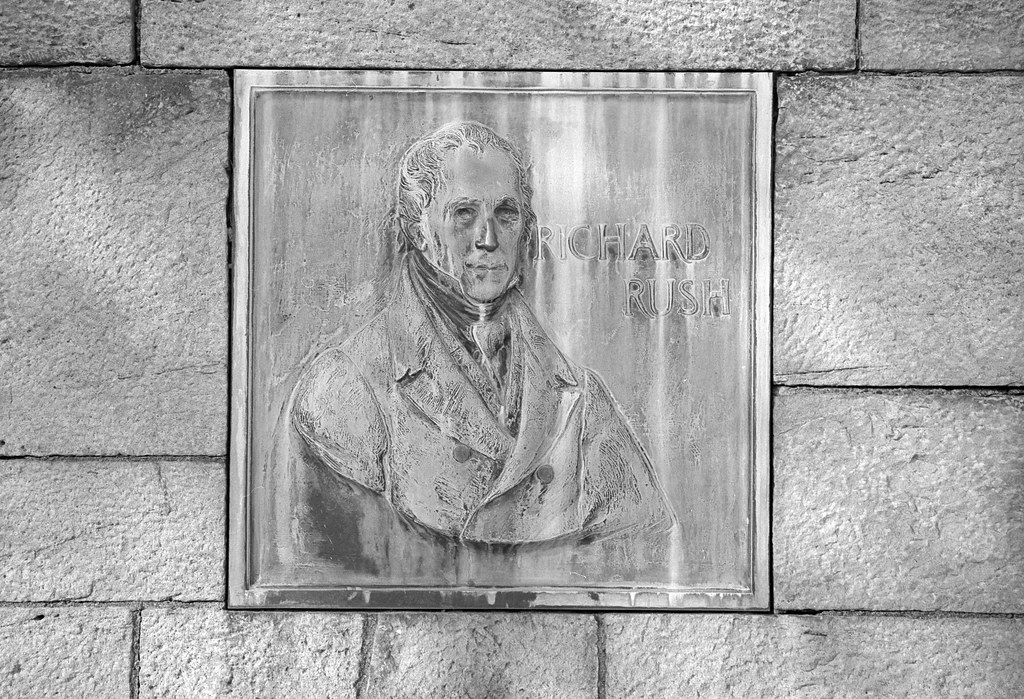

Adams, using his authority as ambassador met with Lord Castlereagh, the Foreign Secretary about negotiating to remove or reduce the naval strength on the internal waterways of British North America. The idea had been brought up before after the American Revolution. Neither side was ready then, but Castlereagh was ready now and sent notice to Charles Baggot to begin an informal discussion with the American Secretary of State regarding options. Baggot opened up talks with James Monroe. However, the talks were never formal, taking place in Washington DC, near where the Columbia Residences are today. When Monroe accepted the nominations for the American Presidency, a replacement, Richard Rush, would continue the talks. Both sides realised that complete disarmament could not happen as questions over sovereignty and piracy demanded some form of defence be present on the Great Lakes. Plus, if the Navies disagreed, they could sell the agreement as a way to cut costs in the era of peace. Throughout the negotiations, the talks never reached the formal level, but after only a few months, both sides agreed that just an exchange of notes made the agreement law. And in April of 1817, both Richard Rush and Charles Baggot signed the agreement and sent the agreement to their respective governments for ratification. The agreement laid out the size and type of ships both sides could field on the great lakes. For the smaller lakes, that is Lake Ontario and Lake Champlain each side could field a single 100-tonne ship mounting an 18-pound gun. For the larger lakes, Lake Erie, Lake Huron, and Lake Superior they could field two ships of the same class. Ironically, both the Royal Navy and the US Navy were already in the process of dismantling their Lake Squadrons. Warships like the St. Lawerence and the HMS Techumseth were stripped of arms, sails, and rigging. The items kept in storage and the hulls kept in Ordinary. For the Royal Navy, they assigned Commodore Robert Barrie to handle the decommissioning of the Great Lake Squadron and construction of the HMS Cockburn (1) which would serve as the first treaty patrol craft. At the Kingston Navy Yards, Barrie had a warehouse constructed specifically to store the ship sails, rigging, and guns for the squadron. The building earned the moniker The Stone Frigate.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tmax 100 @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+50) 12:00 @ 20C

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

The Rush-Baggot Agreement proved that both countries could negotiate in good faith without resorting to violence to resolve issues. After the ratification of the Agreement, both parties began to explore options to close the loop on a few outstanding issues arising from the Treaty of Ghent. Richard Rush joined Albert Galitan travelled to England to open up negotiations with Henry Golburn and Fredrick Robinson to that end. Galitan had previously worked on the Treaty of Ghent and was serving as the American Ambassador to France. Minor matters were quickly wrapped up over ratification timelines and fishing rights off British North American Provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador. But there were more significant items to discuss that proved contentiously. The first being a formal borderline. The frontier had proved difficult since the end of the American Revolution. Between the United States and the Canadas, the rivers and Great Lakes generally acted as the borderline. But once you started going further west past the Mississippi River things got a little more liquid. The idea to use the 49th Parallel came as a compromise, both the Americans and the British would be forced to turn over territory to the other. The British would lose parts of the Red River Colony and Rupert’s Land, while the Americans would shave off parts of the Dakota Territory. The problems began around the Columbia River valley on the west coast. The British maintained control over Vancouver Island, both the British and the Americans claimed the Pacific Northwest, and neither side desired to bisect the resource-rich territory. Both parties agreed to joint administration of the region with the issue revisited in ten years, with the Americans continue to call the area Oregon while the British called it Columbia. The second issue to come up would be the return of property. By this point all the captured territory had been returned to the Americans, the final piece of land being Moose Island on the New Brunswick Border. The property the Americans were referring to was humans, specifically blacks who had fled to Upper Canada or British held territories and received their freedom for service during the War. Slavery at this point remained legal in both the British Empire and the United States, however, in Upper Canada the Act to Reduce Slavery had been in effect since 1796, and despite the colour of their skin, in the eyes of the Empire, these were free men, not property. The issue remained a sticking point, but rather than deal with the issue; they kicked it down the road for an unbiased third party to mediate further discussions. The four men signed the treaty in October 1818.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Portra 160NC @ ASA-160 – Unicolor C-41 Kit

Anniversary Speed Graphic – Schneider-Kreuznach Angulon 1:6,8/90 – Kodak Tri-X Pan @ ASA-320 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:30 @ 20C

Both the Rush-Baggot Agreement and the London Treaty of 1818 were steps forward towards the relationship between Canada, Great Britain, and the United States have today. Slavery ended in the Empire in 1833, and those men who earned their freedom by serving in the British military or through their efforts to escape would never return to the United States as slaves. The border on the east coast between New Brunswick and Maine saw resolution in 1842 after the Aroostook War, and between Oregon and British Columbia in 1846 after nearly sending both Great Britain and the United States to war. These two treaties did not disarm the borders but rather reduced the amount of military force defending them. It would not be until 1871 when Britain and the United States signed the Washington Treaty that the borders completely demilitarised. The Dominion of Canada would be a signatory on the treaty. Throughout the years the Rush-Baggot Agreement continues to be honoured, although both sides can operate warships on the Great Lakes, they are for training purposes only, and both sides notified of the presences of these ships. Additionally, weapons can be installed on ships, but not operated while on the lakes. After the September 11th attacks in 2001, the US Coast Guard requested permission to arm their ships with .50 Calibre Machine Guns, a request the Canadian Government granted as it did not, in a modern context, break the agreement. And while Canadian Coast Guard ships operating on the lakes are unarmed, they reserve the right to arm their ships should the need arise. No memorial to the London Treaty of 1818 exists in Canada, rather the numerous land crossings across Canada are a testament to both the Rush-Baggot, London Treaty, and Washington Treaty today. Both Canadians and Americans can travel between the two nations with relative freedom. The Stone Frigate still operates today as part of the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario, a historical plaque to the Rush-Baggot Agreement is present on the campus. A larger memorial to the agreement complete with the full text is found at Old Fort Niagara in the 1920s. Another memorial sits near the Columbia Residents in Washington DC. You can read the full texts of both the Rush-Baggot Agreement and the London Convention of 1818 online.

1 Comment