There are many figured in our history that changed the course of Canadian History, think Sir John A. MacDonald, William Lyon MacKenzie, Robert Baldwin, Louis LaFontaine. However, all these men owe their contributions to a single person, Robert Gourlay. Gourlay’s presence in Upper Canada would ignite the spark of reform here in Upper Canada. Upper Canada in the early 19th-Century was a vast rural backwater. Urban centres were few and far between cities that we know today were little more than muddy villages in the middle of the vast forest. The undeveloped nature of the Province gave those in control, the colonial elite, access to wealth through the sale and collection of raw materials. Materials to sell on the docks of Montreal and sent home to England to drive the home economy. Resources were the centre of the provincial economy; the few mills processed the raw materials, sawmills made lumber from timber and grist mills ground wheat into flour. The smaller farmers grew enough to support themselves or the sell locally as the roads were little more than mud tracks, even the major highways. The War of 1812 had also left many in the Colonial Elite with a strong Anti-American Slant, and they petitioned Francis Gore, the Lieutenant-Governor to create several laws to prevent Americans from purchasing land in Upper Canada. It was into this environment that Robert Gourlay arrived in 1817; his wife had inherited some land near Queenston.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Distagon 50mm 1:4 – Rollei RPX 25 @ ASA-25 – Blazinal (1+50) 11:00 @ 20C

Robert Gourlay was born on the 22nd of March 1778 in Craigrothie, Scotland. While not born to the gentry, his father did own several farms in their home parish. Gourlay attended both St. Andrews University and the University of Edinburgh, earning an Arts degree from St. Andrews and an Agriculture Degree from Edinburgh. His father put his son to work in managing one of his farms until 1809, after which Gourlay leased and managed a farm of his own. Not only did Gourlay manage farms he also investigated land use and the conditions of the poor farmers in Great Britain. He reported the dire circumstances of the working poor in the country, many little better than indentured servants to the men who owned the land. He presented a radical plan to give these poor a better living wage to improve their condition, and he also suggested that any man who could read and write given the right to vote for their representative in the House of Commons. While both ideas fell flat in the House of Lords, they would sit and grow as an idea throughout the remainder of the early 19th-Century. In 1817, Gourlay would leave Scotland for America. From the United States, he would arrive in Upper Canada in 1818. Gourlay would learn quickly that the situation in Upper Canada reminded him of that which he had left in Scotland and England. In addition to the stranglehold on immigration, the land use in Canada was aimed to only line the pockets of those in the elite, the merchant barons. The land in Upper Canada fell into two major categories; the first was crown land, that land which was owned by the Crown of England and was given to those who did a service for the greater Empire and given as a reward. The second, the Clergy Reserve fell under the ownership of the Anglican Church, and in the mind of Reverand John Strachan was for keeping Upper Canada out of the clutches of the Roman Catholics and other Protestant denominations. The placement of the Clergy Reserve made any town layout look strange, and made it difficult to plan any significant farm, mill, or road. And the Colonial Elite often owed their membership in the inner circle to Strachan, so no one dared challenge the Bishop of York.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

Gourlay, while he had failed to make any dent in the establishment in England, but he felt in the Provincial environment he could affect some level of reform. And in talking to the local population, he knew the disenfranchisement with the establishment and desired some level of reform. In 1818 the only way to get information out to a large population was through newspapers. Newspapers had been around British North America since the establishment of the early colonies. Gourlay used these newspapers to send out questionnaires to any who would read and respond. Gourlay began to receive responses, right under the noses of the Provincial leaders. But it would be Reverand Strachan who would be the first to raise the alarm. While many of the questions were innocent enough, the final question raised many eyebrows at York. It asked for what they felt was holding back the improvement of their district, town, or Province. The Executive worked hard to prevent the questionnaires from getting back to Gourlay. But by this point, Gourlay had escalated his cause and was speaking publicly on the subject of better land use. He encouraged that the population petition the government through their representative in the Legislative Assembly or the Lieutenant-Governor directly or go directly to the Colonial Office. The elites tried to silence Gourlay, first by having thugs assault him, and when that failed had him charged with Liable. The overinflated charge failed to stick. It wasn’t until Reverend Strachan brought the case of Gourlay to the attention of his former pupil and Attorney General of the Province, John Beverly Robinson. Robinson found the actions alarming and recommended that the executive change tactics and have Gourlay charged with sedition under the 1804 Alien Sedition Act. Governor Maitland who wanted to maintain loyalty and calm in the province agreed and had Gourlay arrested. Despite the fact, the law was to prevent foreign (American) influence in Upper Canada, and not for use against a subject of the Crown. Maitland only wished to avoid open rebellion. Robison made quick work of the case against Gourlay, and while they desired to have him imprisoned, maybe even hanged, they could do neither. The only choice they had was banishment and Gourlay gladly accepted exile.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-400 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:00 @ 20C

Despite being removed from the Province, Gourlay first went to the United States again to sell his land use surveys in the American Midwest, but when that fell flat, he returned to Scotland. There he penned a report and published it in 1822. A Statistical Account of Upper Canada never proved to be a best seller, but it caught the attention of enough people to move towards some level of land reform in Upper Canada. One of the men who would back this was John Galt, who incorporated a colonization corporation under the name the Canada Company in 1827. But Gourlay’s trials in Upper Canada sent him on a downward spiral, and he spent several years in a Mental Hospital. Even from the hospital, he continued to write for all his causes. And many in England began to listen, the Reform Act in 1832 granted all who were literate a vote for their representative in the House of Commons and 1834 new Poor Laws granted a living wage to all. Sadly these changes never trickled down to Upper Canada. But thanks to Gourlay’s actions, the reform movement had taken hold despite the efforts of the elite to crush those who felt the same as Gourlay. The Society for Constitutional Reform began to grow in both membership and influence, and in 1836 they managed to pass a bill to remove the banishment from Gourlay. However, Gourlay did not look kindly on MacKenzie’s radical brand of reform and denounced his fellow Scotsman and his rebellion. But it wouldn’t be until 1842 that his arrest was deemed illegal and they offered a small pension to Gourlay. Gourlay refused, claiming to be a creditor of the government. Gourlay would return to Canada in 1856, purchasing a small plot of land near Mount Elgin and run for the Legislative Assembly. He would lose his run for Parliament and return to Scotland in 1858. He would retire in Edinburgh and pass away on the 1st of August, 1863.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-400 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:00 @ 20C

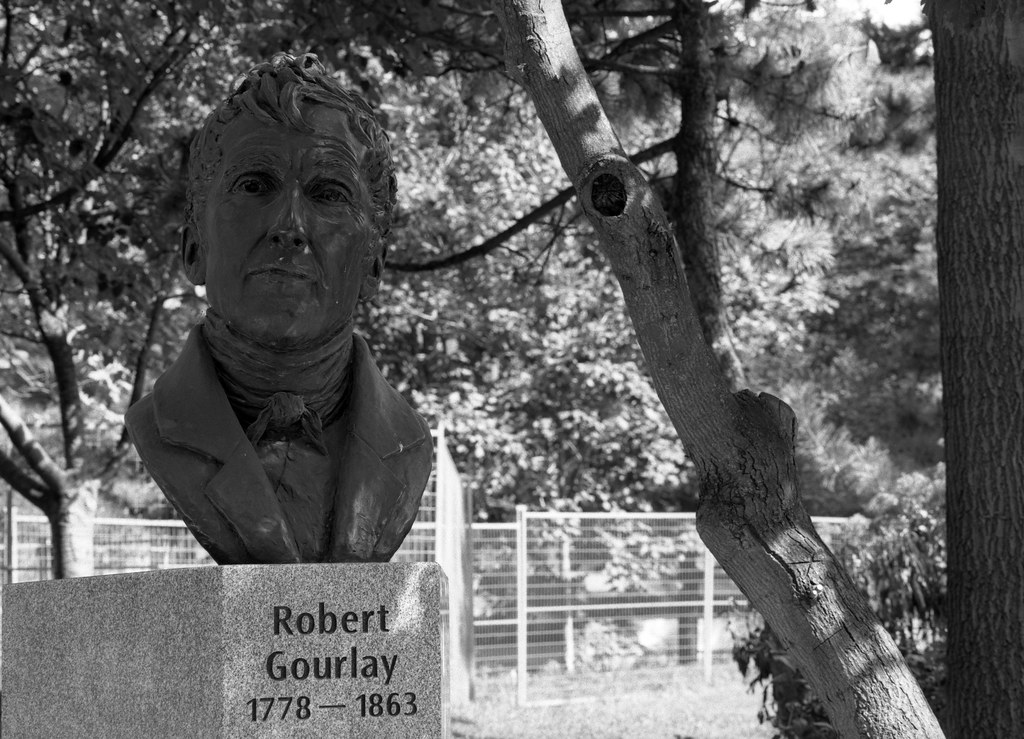

Today, there is little in Ontario to remember Gourlay. A historical plaque marks the area where he attempted to purchase land before his run-in with the Colonial Elite in 1817, and would eventually purchase in 1856. A bust of Gourlay with a list of his three accomplishments can be found in St. James’ Park in downtown Toronto. The Clergy Reserve would be ended in the 1850s thanks to the efforts of William Lyon MacKenzie’s second involvement in Canadian politics. The Canada Company would prove to be the greatest single push in colonial expansion since the founding of Upper Canada. And while Gourlay is not widely known or remembered in Canada, his efforts to secure a vote for all, a living wage for all, and better land use in Upper Canada are tribute enough.