If there is a singular piece of infrastructure that changed the course of an entire region of Ontario that piece is the Welland Canal. Today the massive ship channel that serves as an extension of the St. Lawerence Seaway has humble beginnings. Before the construction of any canal, the only way to move supplies between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie was using the Niagara River. The river proved to be a difficult route for the British. The first being proximity to the American guns at Fort Niagara the second being the wonder of Niagara Falls. It resulted in long portages often starting at Queenston. The other waterways across the Penisula were not suitable for ship traffic either as they featured rapids and other navigation hazards. During the post-war era, the British Army investigated making a canal out of the Grand River, but nothing came from that. However, in the post-war years, many prisoners returned to Upper Canada. Among them, William Hamilton Merritt. Merritt, born on the 3rd of July 1793, his family would be among those United Empire Loyalists who fled the United States. Merritt served in a militia Dragoon Unit and was taken prisoner during the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. His time in prison gave him time to think over his idea to build a channel to bypass the Niagara River. When he returned, more pressing matters arose, such as the need to make money. After settling in Queenston first, he returned to St. Catherines after purchasing a plot of land on the Twelve Mile Creek with a rundown sawmill and a salt spring. From his parcel of land, Merritt operated a small general store, making use of the salt spring and a brewery he constructed. These provided enough income to being rebuilding the sawmill. The trouble with the mill was that the creek did not provide sufficient water to drive the machines. Merritt came up with an idea to dig a channel to divert water from the Welland River. The trouble came from the Niagara Escarpment.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Rather than seek out additional help from fellow business owners to back a project that only supported his own business, he returned to his old idea of a shipping channel across the Penisula. It was that idea that he presented to a group of business owners in St. Catherines. In a meeting on the 4th of July 1818 not only did he get his neighbours to sign a petition and offer up startup capital, but they also advised him to take the appeal to the Provincial Government and get them to sign onto the project. The death of King George III in 1820 delayed the hearing of the project, and it wouldn’t be until 1824 until the Parliament heard Merritt’s proposal. But the men of the Family Compact had managed to consolidate their power, and the canal offered something that the Military proposal on the Rideau Waterway did not, a way to move their goods and gain better access to the American markets. And in the final act of the 8th Parliament of Upper Canada, they created the Welland Canal Corporation on the 19th of January 1824. Merritt would get to work, using the capital already raised, he courted more investment from the elites of Upper Canada, England and even America. With the opening of the Erie Canal connecting Buffalo to New York. Merritt visited the canal to get an idea for his own and managed to hire Alfred Barrett, an engineer who worked on the Erie project for his own.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Between Merritt and Barrett they plotted the route the new canal project would take, like all canals of the era they were planning on making a series of rivers across the peninsula navigable. Ships would enter the canal at the Twelve Mile Creek on Lake Ontario; a natural harbour made it a perfect spot. The problem remained in climbing the Niagara Escarpment. The DeCews, presented the idea of an incline railway to bring ships up and down at DeCrew’s Falls; however, both men realised such a system would cost far too much. A set of flight locks would carry ships up and down the escarpment, and join the Welland River at the top. Ships would continue to follow the Welland River and exit onto the Niagara River at the village of Chippawa. Much to the dismay of the DeCews, the planned route cut their mill off from Twelve Mile Creek as they needed to divert the waterway through St. Catherines. The locks were to be constructed out of wood to save money and speed up construction. And on the 24th of November 1824, the men in charge gathered at the crest of the Escarpment and held a grand ceremony to start the construction with a ceremonial earth turning ceremony. The bold act started a five-year countdown to completion as laid out in the company charter. The promise of work brought hundreds; thousands of men employed in digging out locks and expanding the creeks. The work was backbreaking and unsafe by modern standards. But communities sprung up around the locks sites, as workers brought their families. On Lake Ontario Port Dalhousie grew, other communities of Allanburg, Merriton, Port Robinson, Welland, and Thorold started at rough work camps.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Accidents did happen, and hundreds of men lost their lives on the project. The largest by far happened at Port Robinson and revealed a flaw in the design. A series of collapses killed many and showed that the Welland River did not have the water level to support the large channel needed to bring the ships from the flight locks to the Welland River. The collapse threatened to end the whole project. Instead of letting the project end, incomplete and with nothing to show, they moved fast and dug a feeder channel to bring water in from the Grand River. It did the trick, and exactly five years to the day, the 30th November 1829 the first ship sailed the channel. A schooner by the name of Anne & Jane, and a grand affair it was as it travelled smoothly from Port Dalhousie to Chippawa before going onto Buffalo. The new canal operated on a system of 37-locks. But it did far more than provide a way to move across the Niagara Penisula it also provided waterpower to businesses which sprung up in the work camps which had become communities in their own right. And the Welland Canal was more than happy to sell the water power to any who could afford it. But it soon became clear that the exit at Chippawa would prove to be a navigational hazard. The proximity to the Falls and the need to still travel the Niagara River proved challenging to get ships both in and out of the Welland Canal. Initially, the corporation planned to dig out and expand the feeder canal and place the exit to Lake Erie at Port Maitland. It would be the natural deep harbour at the settlement of Gravely Bay that proved to be the perfect terminus for the Canal.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta AF Zoom 35-70mm 1:4 – Kosmo Mono 100 @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+50) 7:30 @ 20C

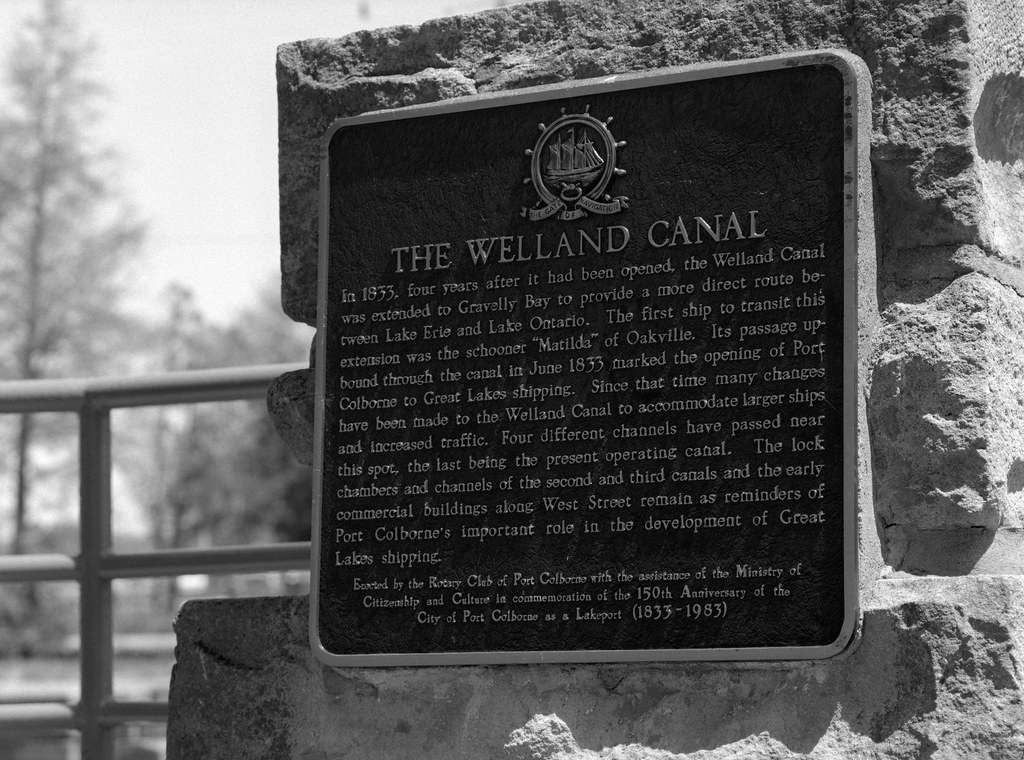

Despite a Collora epidemic sweeping the province work commenced in 1831 to dig out a new channel to connect the Canal at Port Robinson to the new terminus at Gravely Bay. The work proved just as backbreaking as between Port Robinson and Gravely Bay cut directly through the Wainfleet Swamp, giving rise to Malaria among the workers. And in 1833 the Canal reopened with the new Terminus at Gravely Bay. As the village’s prominence grew, they would rename themselves Port Colborne in honour of the Province’s Lieutenant-Governor. Merritt’s success in building the canal gained enough popularity that he ran as a Tory in the 1832 elections, winning his seat. His involvement also earned him a spot on William Lyon MacKenzie’s blacklist as a member of the Family Compact. While connected to the cadre of elites he was never a formal member of the group. The canal brought prosperity and rapid settlement of the area; port cities would become centres for shipbuilding and hospitality industries. Mills purchased water power from the corporation and became centres of communities as well. As the years went on, the canal’s infrastructure began to suffer, the wooden structures, doors, and workings were slowly falling apart being in a state of constant damp. And by 1836 the Welland Canal Corporation and the Upper Canada Parliament began to discuss a government takeover of the canal to gain income to repair or rebuild the locks. The Upper Canada Rebellion delayed the acquisition until 1841. For Merritt, he continued to serve on the Legislative Assembly in Upper Canada and the United Provinces of Canada. In his role, he supported free trade and even assisted in the construction of the first bridge over the Niagara River to carry the Great Western Railroad into New York in 1857. In 1860 he was elected to the Legislative Council. He would pass away aboard a ship docked at Cornwall on the 5th of July 1862 and is buried today at Victoria Lawn Cemetary in St. Catherines, Ontario.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Today much of the First Canal was swept away and upgraded when the Second Canal was construction in 1841. The Second Canal followed much of the original route, and many of the first locks were demolished, dredged and reconstructed out of limestone. These locks still exist today and can be seen in many parks and trails through St. Catherines and the other communities. The original entrance is now underwater just off the beach at Port Dalhousie. A small stretch of the original canal and the Twelve Mile Creek a can be seen near Welland Vale Island, the site of Merritt’s mill, although the site is unmarked and occupied today by Biolyse Pharma. Although there are several historical plaques that mark key spots on the canal, such as Lock Six in Confederation Gardens, the start of the Canal at Allanburg, and the historic exit at Port Colborne. While rare, recent archaeological excavations have uncovered remains of wooden locks from the first canal. The communities that owe their existence to the canal are thriving today though once independent are now part of larger towns and cities in the area. Communities like Merritton and Merrittville take their name from William Hamilton Merritt. In St. Catherines a statue to Merritt stands at the intersection of St. Paul West and McGuire, overlooking part of the original canal. Merritt also lends his name to a Public School and Library in St. Catherines, the School standing on land that once was part of the Third Canal. In the region around the Canal, the legacy and history of the Canal are well-liked and maintained by a passionate group of people, spearheaded by the Welland Canal Advocate. The WCA hosts hikes through the historical sections of the Canal throughout the year, and their next hike takes place on the 27th of April, you can find the details on their webpage. But the greatest legacy of the First Canal is the current Fourth Canal which remains today a key part of the St. Lawerence Seaway and the trade it carries across the entire Great Lakes waterway and to the world as a whole.

1 Comment