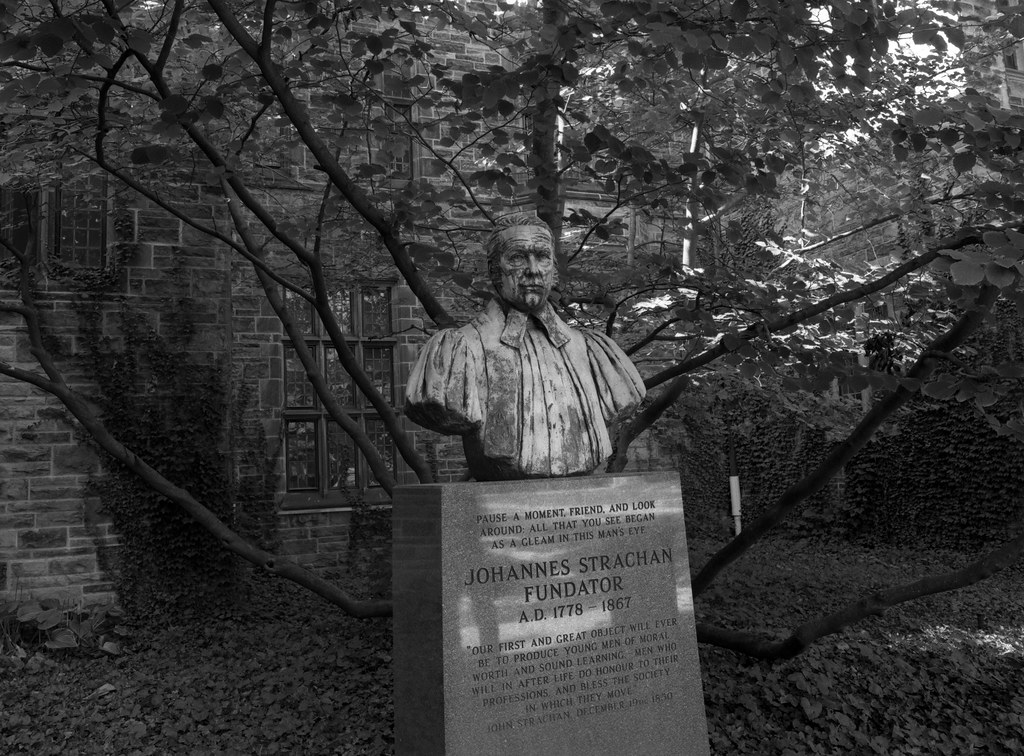

If there is a single figure in the lead up to the Upper Canada Rebellion, the opposite of William Lyon MacKenzie, a Tory among Tories, that figure is Sir John Beverly Robinson. There is no better example of a loyalist and the perfect man to head up the Family Compact and pull the strings of the Provincial Government for many years. While having no love of power, he was a man of strict ideals, and for that, he took the role seriously and refused to allow anyone to deviate from his moral compass. John’s family’s legacy traced back to the Robinsons who were among the first families in Virginia. His father Christopher fought with the Queen’s Rangers during the American Revolution before the regiment left the colonies, evacuated to New Brunswick. There Christopher met and married Easter, the daughter of a well known Anglican Priest. The two would marry in 1784 and moved to Berthier in Lower Canada. They had their second son there, John Beverly on the 26th of July 1791. With Christopher studying to become a lawyer the family moved to Kingston in Upper Canada, but the death of Christopher in 1798 saw John’s mother relocate to York (Toronto) to live with his older brother, Peter, who was also studying to take up law. John, however, remained in Kingston in the care of Reverand John Stuart. Reverend Stuart, being a close friend of his father and executor of his estate enrolled John in the school of John Strachan. And when Strachan saw ordination as an Anglican priest and sent to Cornwall, John followed. Reverend Strachan would befriend the young man, opening his home to him while he studied under him at Cornwall.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

Robinson would leave Cornwall and with the backing of both Stuart and Strachan study law under the Provincial Solicitor General, D’Arcy Boulton. John proved an apt pupil, he read, studied hard, and socialised easily. He would take in debates in the Provincial Legislature and significantly improve his standing among the upper class of Provincial society. His high-standing and connections with Boulton and Strachan gained him a place in a small circle of students favoured by the Chief Justice for Upper Canada, William Drummer Powell. John was a part of the inner circle, and with these connections he volunteered for a place in the flank company of the York Militia, being commissioned an Officer in the Provincial Militia. When war broke out in 1812, John was among those units who marched with General Sir Issac Brock to reinforce the western frontier participating in the siege and capture of Detroit. And when Brock achieved victory returned to the Niagara region. Now a captain and in nominal command of his company, John would march under Colonel John MacDonnell in the second wave of British troops attempting to recapture the heights and then join in the final assault under General Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe. Being in the militia, John’s company would escort the American prisoners back to York. It was here he learned that the Americans had captured D’Arcy Boulton and that he was now the Acting Attorney General for Upper Canada. A position not usually granted on a twenty-one-year-old law student had yet to be called to the Bar. But John had the right connections with Powell and Strachan. Despite his role, he stood up with the York Militia during the American invasion in April 1814 and became part of the group of officers with the aid of Reverand Strachan to negotiate the town’s surrender. As Attorney General, he handled many day-to-day cases, but his biggest contribution to the war was in prosecuting the Ancaster Assizes of 1814. In total nineteen men were tried through the spring and summer of 1814, fourteen were found guilty, and eight men were hanged at Burlington Heights for Treason. At the end of the war, Boulton returned from prison resumed his role as Attorney General with Robinson taking the Solicitor General posting.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

At the urging of Reverend Strachan and with the permission of Lieutenant-Governor Francis Gore, Robinson took a leave of absence and returned to England to complete his legal studies and be called to the English Bar as a lawyer. With the aid of Strachan, Robinson had many high-level contacts within the British aristocracy. When he arrived he met with Lord Bathurst, Secretary of War and the Colonies, the Solicitor General for the United Kingdom and William Merry, Undersecretary of War. At Merry’s home, he met one Emma Walker, whom he married on the 5th of June 1815. He would use his spare times to travel around England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, but with his leave having been extended three times already, he would return home to Upper Canada. When he returned in 1818, his mentor D’Arcy Boulton saw a promotion to Chief Justice, and Robinson took on the Attorney General post, a job he took seriously which also allowed him to pursue his private practice. It would be at the urging of Reverend Strachan that Robinson turned his attention to Scottish reformer Robert Gourlay. Gourlay’s questionnaire raised the alarm among the province’s elites and most wanted him gone, an earlier liable suit failed, and with the urging of Strachan and the governor, Sir Peregrine Maitland, Robinson raised a case against Gourlay under the 1804 Alien Sedition Act. The case succeeded and Gourlay banished from Upper Canada. The case gave Robinson a name among the Provincial Leaders, his personal beliefs, ideas, and ideals made him a centre point for the Conservative elites, and in 1820 with the backing of Strachan and Maitland, he ran for a seat in the Legislative Assembly winning a seat in his home district of York. In the assembly, he among other conservatives petitioned for expansion of the province but strictly controlled allowing only British immigrants, and continuing the policy of keeping Americans at bay. He had no love for the American style of government and often defended the position going back to England to advise Lord Bathurst on the situation in Canada. While serving in the Assembly, he would get the appointment to the Legislative Council giving him more power and influence. His position as Attorney General, Legislative Assembly Member, and Legislative Councillor made him the perfect patriarch to gather like minding men together in a loyalist club, or rather Family Compact.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

Robinson and other members of the Compact and their allies quickly found themselves in the crosshairs of the fast-growing Reform Movement, while many desired change within the rule of law and the Constitution, others desired more radical change. These radicals found their leader in William Lyon MacKenzie. Robinson had a great dislike of MacKenzie, privately referring to him as vermin. The two ideologies clashed in the Assembly, and his role as Speaker of the House, Robinson often had to mediate between the two. His legalistic approach, use of the Consitution, allowed him to get legislation through the Assembly even with a deep divide. His appointment to Chief Justice and the arrival of Sir John Colborne as the new governor saw a brief dip in his influence. A report called into question the placement of members of the judiciary in political roles and recommended that they either resign from their judiciary roles or their political roles. This did not sit well with Robinson, and while his influence in England was strong, it was not strong enough. He would remain in his role a Legislative Councillor but could only advise on legal matters. But if there was one thing that Robinson was pleased about, it was his freedom from Colonial Politics. He did maintain his placement at the centre of the Compact and could still exert some influence on Provincial Matters through his friends and allies. As MacKenzie’s influence grew and his crusade for radical reform turned towards an American Republic, it would be Robinson who penned the response to the Colonial Office, providing a much closer friendship with Governor Colborne. Colborne’s replacement, Sir Francis Bond-Head proved a much closer ally of Robinson and Robinson would be more than happy to provide advice to the ill-suited governor. When the threat of rebellion grew, both Robinson and Bond-Head downplayed MacKenzie’s threat to the public to provide an air of calm hoping to defuse the situation. And when the alarm rang out, Robinson stood up to be counted among the militia, but on the 7th of December 1837, he would sit in his home, Beverly House, which stood at John and Richmond Streets in Toronto penning his account of the rebellion. Bond-Head was even willing to push to have Robinson knighted for his part in the Rebellion, an honour Robinson turned down. When Bond-Head was recalled, his replacement worked closely with Robinson, who had the task of presiding over the trails of those connected to the Rebellion. Some 900 prisoners were waiting for trail and while a majority were released without charge bonded to keep the peace. Robinson took the same care as he had in the Assembly in the courtroom, each man brought forward judged against the law, and with two separate pieces of legislation and the ear of the Lieutenant-Governor, Robinson executed justice with a clear conscious. He reserved the death penalty only for the leaders of the rebellion, notably Peter Matthews and Samuel Lount, and their American co-conspirators.

Robinson had this Regency Style Cottage Built as a personal retreat, hunting lodge, and office space in his role as Executor of Land Sales in the Toronto Township in 1828.

Pacemaker Crown Graphic – Schneider-Kreuznach Symmar-S 1:5.6/210 – Kodak Tri-X 320 @ ASA-320 – Kodak D-76 (Stock) 9:00 @ 20C

While Sir George Arthur often saw eye-to-eye with Robinson, the Governor General, Sir John Lambton did not. Robinson did not like the liberal, who often desired more merciful punishments for those connected to the rebellion in hopes that they would not be made martyrs to the cause. Illness forced Robinson to return to England for medical treatment in the middle of 1838, and while there he took the chance to again speak to his many contacts in the circles of power. He was displeased with the portrayal of the Family Compact in Lambton’s final report on the rebellion, although pleased that the blame did not land on him and his allies. While he agreed in principle with the Union of Upper and Lower Canada, he felt that the French-Canadians would have undue influence on Upper Canada, he had worked hard to help shape the province into the ideal haven for the Loyalists and their families. But the power base both in Canada and England had changed, and Robison would be politely asked to leave in 1840. But England was not ready for vast reaching reform, and many of the new governors sought help from the Conservative backbone, and Robinson would maintain he role as Chief Justice for Canada West in the new United Province. But Robinson realised his influence in Canada had come to an end, his friends and allies were gone, or changed sides. Now an outsider in the political game, he continued to serve on the Queen’s Bench and his private practice. Outside of that, he worked closely with the Anglican Church, his other friend Bishop Strachan approached him with an idea to charter a new university following the secularisation of King’s College in 1847. When responsible government arrived in Canada in 1849, Sir James Bruce again approached Robinson about a title, this time Robinson agreed. Bruce originally planned to recommend Robinson be made a Companion in the Order of Bath, but a snide comment from Robinson saw the title changed to 1st Baronet of Toronto. When Strachan established Trinity College University, Robinson accepted the role of Chancellor in 1852. With age and ill-health closing in and an attack of gout in 1861 Robinson resigned as Chief Justice but did not retire, instead of taking an appointment in the Court of Error and Appeal. He would again face an attack of gout in early 1863 and retire for good. He would not survive the year, taking communion from Bishop Strachan on the 28th of January 1863, he would die on the 31st.

Intrepid Camera 4×5 – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 – Kodak Plus-X (PXE) @ ASA-64 – Blazinal (1+100) 10:00 @ 20C

Despite his connection to the Rebellion and the Family Compact, Sir John Beverly Robinson is remembered well in legal circles. As Canada’s longest serving Chief Justice, his judgements and cases are still today studied by law students and legal historians. He was a man made from how he was raised and who raised him, a strong believer of the union of church and state and the school system. He felt that only the church could offer guidance and a strong moral compass to guide schooling and good government. He believed in a system where one’s connections would allow for their advancement in society. He disliked power, taking on the political role only because he believed it was what he was raised for and that it was his duty as a subject of the crown. And while his bias towards the rule of law and the constitution is clear, he felt that was the only way to be a fair non-biased judge. And still, today is held in high esteem. While today there is nothing overt to remember Sir John Beverley Robinson, his grand home in Toronto which one sat at John and Richmond’s street was demolished in 1911 to make room for the new Methodist Church headquarters, which today still stands as the Bell Media Building at 299 Queen Street West in Toronto. Although the Toronto Public Library has several images of the exterior and interior of the house. His other home, built in 1828 still stands as the Robinson-Adamson Home, better known as The Grange in Mississauga it saw extensive restoration from 1978-81 and today is home to Heritage Mississauga. But Robinson’s greatest contribution was to the legal system in Upper Canada, and the Law Society of Upper Canada still stands at their original headquarters at Osgoode Hall which still stands today in Toronto, and there’s a good chance many of Robinson’s cases, and papers are stored in the extensive library found there. While many could cast Robinson into the role of a villain in the troubles of 1837-8. We have to throw an unbiased eye on him as he did as a judge, he was only human, and fairly judged what was happening under the rule of law at the time, for good or for ill, he must be remembered for both the good and the bad he did in the greater story of Canadian history.

2 Comments