The sheer amount of aid rendered to the Canadian Rebels and the fact that many raids by the rebels came from the United States again proved that Canada remained open to invasion as it always had before the rebellions and even before the War of 1812. It also showed that the post-war practice of reducing colonial garrisons as a cost-saving measure might not have been the best option indicated in the fact that Bond-Head sent all the regular troops in Upper Canada to shore up Colborne in Lower Canada. While the militia enjoyed many victories in 1837 but these were against poorly armed and lead rebels, it would be the British Army that did most of the heavy lifting in the later conflicts of 1838. But by 1838 the military authorities in London were moving material back to Canada to raise the old garrisons from ruin once again.

Nikon F5 – AF Nikkor 50mm 1:1.4D – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-800 – Ilford Microphen (Stock) 11:00 @ 20C

The first new fortifications against the rebellion went up in early 1838 in Toronto. While Fort York defended the harbour the issue of protecting the northern limits of the city became a significant question. MacKenzie’s march from Montgomery’s Tavern proved that the roads in and out of the city remained open. Funding for the construction of three blockhouses was secured, and construction began in earnest. Two blockhouses were raised to watch the main roads in and out of the city, Yonge Street in the east, in what is now Bud Sugarman Park, and Spadina Avenue in the West where the Daniel’s Building stands today. A third blockhouse guarded the Rosedale Valley at the modern intersection of Bloor and Sherborne. Each blockhouse followed the same pattern of two stories with the top storey at an angle to the first. Each had space and provision to support forty men, drawn initially from the local militia units and later by the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

For Toronto, they had a garrison in the form of Fort York, but for Amherstburg and Prescott sites of significant engagements during the rebellion, their forts had long fallen into ruin in the post-war years. At Amherstburg, reconstruction of Fort Malden began in 1838 with much of the work completed by the men of the 34th (Cumberland) Regiment, the old earthworks were raised up, and wooden buildings were constructed to house both men and supplies. The 1815 barracks saw continued use and the addition of a pair of two storey buildings to accommodate the increased number of troops. The fort would have several redoubts to house enough artillery to repulse any land or water assault. At Prescott, the general layout of Fort Wellington remained the same, a single blockhouse in the centre of tall earthwork walls. The old wooden blockhouse saw demolition and replacement by a three storey stone blockhouse complete with a well inside the structure. The old casemates were filled in to allow for taller walls, the fort’s original pair of twenty-four-pound guns were remounted and placed to watch over the river, supported by a couple of large howitzers. A rifle gallery extended out beyond the walls to give the defenders a better range of small arms fire against any landing invaders. The fort was completed with a stone gatehouse, wooden palisade, cookhouse, latrine, and guardhouse. But the British Army in Canada faced an even bigger threat that came from inside their ranks, desertion. Canada provided a disaffected soldier with plenty of places to run and hide to escape the harsh discipline of army life. And the practice had been prevalent since the early days of the colony, the one thing that the British Army would do is establish veteran units, open to men who had a specific number of years of service and ethical conduct. These regiments often had easy garrison duties and usually got paid more, one of the more famous units, the 10th Royal Veteran Regiment were part of the first British attack of the War. But for Canada, Lord Wellington had something specific in mind. Wellington had seen the potential of green-jacked speciality rifle units during the Napoleonic Wars with the use of the 60th (Royal American) and 95th (The Rifles) Regiments, even in Canada the Glengarry Light Infantry proved their worth in the more skirmishing style battles of the backwoods. The Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment stood up in 1840, clothed in a uniform similar to that of the 5th, 6th, and 7th Battalions of the 60th (Royal American), the unit wore green and carried the famous Pattern 1800 Infantry Rifle, or Baker Rifle in popular terms. Soldiers of good conduct and fifteen years of service could join the new unit. A standard rifleman would earn two shillings a day in pay, double the amount of a private in the British Army at the time. And after twenty-one years of good service would receive a pension and a land grant in Canada. The unit would not use the Baker Rifle for long, receiving the Brunswick Rifle in the mid-1840s. While the Brunswick Rifle used a more reliable ignition system in the form of a percussion cap, the grooved ball proved annoying to load in any quick manner. By the 1850s the Brunswick Rifles were phased out and replaced by Pattern 1853 Enfield rifled muskets. One thing to note about the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment is that they never fought together as a single unit, instead, they were broken up into brigades, companies and detachments and spread across all the British North American Provinces serving alongside British Army regulars and often garrisoned in cities, towns, along the Rideau Canal, and forts.

Modified Anniversary Speed Graphic – Kodak Ektar 203mm f:7.7 – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-400 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:00 @ 20C

The final fort to see construction in Upper Canada took place in Toronto. By the 1840s Fort York no longer could command the entrance into the city’s harbour and as the garrison grew so did the number of buildings at the old garrison and space had become crowded. Captain Thomas Gleeg of the Royal Engineers set about designing a new fort for Toronto. He placed the fort at the site of the old Western Battery, allowing it to defend the harbour better. Six buildings formed a semi-circle, surrounding a central parade square, around the buildings tall walls to house the artillery battery. The construction material was Queenston Limestone to give the new garrison a handsome appearance. Most of the buildings were a single-storey while the officer’s quarters and mess stood at two-storeys at the top of the semi-circle. The other five buildings housed the enlisted men, administration offices, and storage. Tall metal gates controlled access into and out of the fort. By the 1850s the Toronto blockhouses were all forgotten with the Spadina blockhouse demolished in 1854, the Young Blockhouse fell into abandonment, and the Rosedale one converted into a private residence. In 1859 the British Army closed Fort Malden, turning it over to the Province. The Provincial Parliament turned the old fort over to the Toronto Lunatic Asylum who faced increasing overcrowding and needed a new space to house their patients. The old fort provided a pre-built secure structure, and the Malden Lunatic Asylum opened the same year. Many buildings were converted to new uses and many more built, notably a handsome administration and laundry building; much of the work being completed by patients. By the 1860s the presence of the British Army in Canada again saw reduction and both Fort Wellington and New Fort York were turned over to the Provincial Government who used them as training posts for the Active Militia and later the Permanent Force and the North-West Mounted Police. By 1870 the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment stood down for disbandment, and the entire British Garrison departed Canada for good. The Malden Asylum closed in 1875, and the land quickly parcelled out and sold to both private and commercial interests. The buildings were either demolished, moved, or left in place and converted to a different use. New Fort York took on a new name in 1893 to Stanley Barracks after Lord Stanley of Preston, then Governor-General of Canada. Although he is better known for the Hockey Trophy.

Nikon F6 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

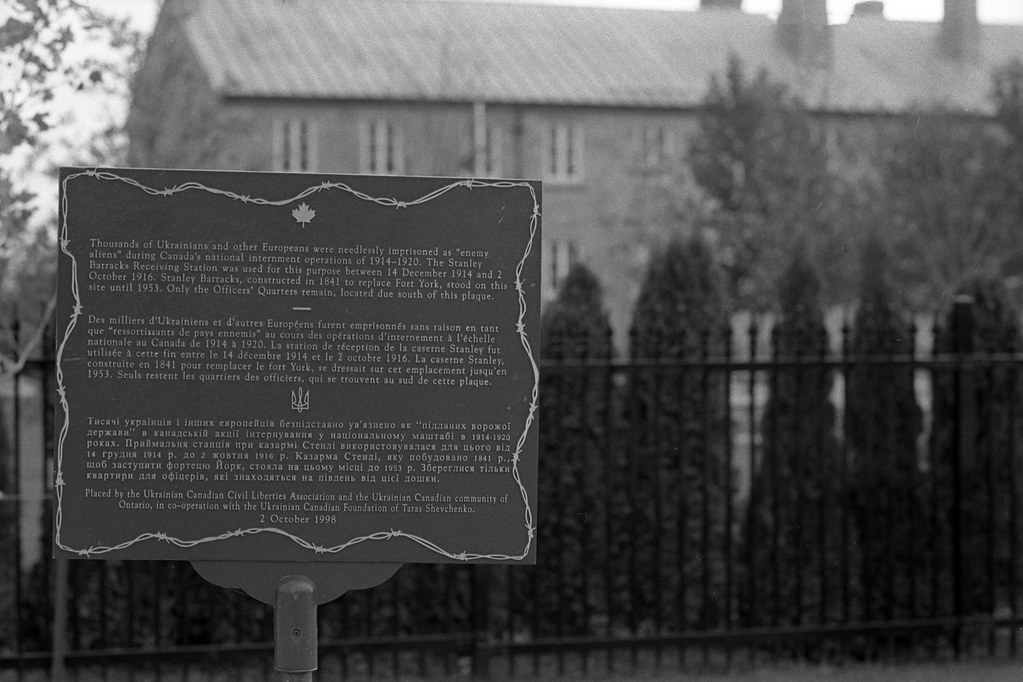

Officially both Stanley Barracks and Fort Wellington were under the control of the Militia Department and saw continued use into the 20th-Century. During the First World War, Fort Wellington provided a staging area for troops heading towards Halifax and the Western Front in Europe. Stanley Barracks provided a far darker purpose as an internment camp for Canadians who were of German, Austrian, Urkanians and others labelled Enemy Aliens by the government, the internment camp operated until 1920 when the last occupants were released. Fort Wellington would be turned over to Parks Canada in 1923 around the same time as Old Fort York became the property of the City of Toronto. These two forts saw extensive renovation and restoration to become public museums. The move gained traction and a way to create jobs during the Great Depression, and by the 1930s many colonial forts saw reconstruction and restoration as museums. Despite the former garrison lands in Amherstburg being now separate properties, the site did not get overlooked. All three levels of government worked together to piece together the area where the fort once stood, through seizure due to back taxes, direct purchase, and a bit of convincing. But by 1946 the property was again whole, and the former site opened as a museum. The only site that did not survive in entirety would be Stanley Barracks, with the expansion of the Canadian National Exhibition in the 1950s all but the Officer’s Quarters were demolished.

Nikon F6 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Thanks to all the preservation work done in the early 20th-Century many of these sites can be visited today. Fort Malden, while it lacks many of the original buildings has preserved several earthwork redoubts and the 1815 barracks. And while most of the military buildings are gone, they are outlined and marked by plaques on site. The asylum laundry stands as it became a private home and now serves as the site museum. Site staff portray members of the 34th (Cumberland) Regiment of Foot from the 1830s era to bring the site alive. In contrast, Fort Wellington remains for the most part original, the earthworks, gate, blockhouse and even the artillery all date to the original construction. Only the wooden outbuildings are modern reconstructions. The site staff portray the site as it would have stood in the 1850s with some employees portraying members of the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment. The Officer’s Quarters of Stanley Barracks stand next to Hotel X and are operated today as a private event space with plaques to mark the historical significance and a memorial to the men, women, and children who were imprisoned there during the First World War. The gates were also saved and are displayed alongside many other remains of historical Toronto buildings at Guildwood Park Only the three Toronto Blockhouses are forgotten, none of the three sites has plaques, although there are (or were) plans to have one at Bud Sugarman Park, however, when I was past there in January I saw none. But you can find both sketches and watercolour paintings of the blockhouses in the Toronto Archives.