The Welland Canal had brought expansion and growth to the Niagara Region, along the canal work camps flourished into settlements, villages, and towns. But the canal remained under private control, and to maintain the wooden infrastructure they needed income from ship traffic and the fees paid to transit the canal. The trouble with the wooden structures is that they were getting old and starting to fall apart and by the start of the troubles of 1837 many of the locks could no longer function. And with the canal at standstill ships could not transit therefore no money would come to the canal, so the locks remained closed. The Corporation approached the government in 1836 to purchase a majority in the corporation which would give the canal a fresh infusion of capital needed to repair or even rebuild the canal locks. The problem facing the government is that they were nearly bankrupt and the province was sliding towards rebellion. The government decided to wait until everything stabilised.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Rollei Superpan 200 @ ASA-200 – Blazinal (1+100) 60:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

For the government the union of the two provinces into a single province had some level of financial gain, the surplus in Lower Canada cancelled the debt of Upper Canada with funds to spare. The new Parliament began negotiations to make the purchase a majority share and bring both the Canal and the Canal corporation under government control. Government engineers began to plan the canal’s reconstruction and expansion. Since the construction of the original canal, the size of ships that now travelled on the great lakes had increased thanks to the improved navigation along the St. Lawerence River. Each lock would need to be made deeper and broader, and a minor change to the route as well as the entrance lock at Port Dalhousie was required. These changes required a new channel dug past Merritt’s mill, cutting it off from the canal for good. The locks would get an upgrade; the new locks were constructed from Queenston limestone on the walls with heavy wooden doors and iron infrastructure. Exactly how the locks on the Rideau Canal had been constructed. At Port Dalhousie, the original entrance to the canal extended out into the lake, the new entrance would be constructed further inland. This move allowed expansion of the town’s natural harbour, so ships did not have to enter the canal before tying up and staying in the town.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Construction would kick off in 1842; the new canal took on two nicknames, the Government Canal or the Stone Canal. Hundreds of workers flooded the region, many employed in the demolition of the old canal locks and dig them out. Stonemasons from Scotland cut and fitted the walls. Work also undertook the widening of the feeder canal to the point where they could send ships onto Lake Erie either through Port Colborne or through Port Maitland. Additionally, a turning basin and lock in Welland opened up access to the Welland River allowing growth in Wellandport and Port Davidson. By 1845 the new canal opened to little fanfare, but the effects of the new canal began to manifest quickly.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

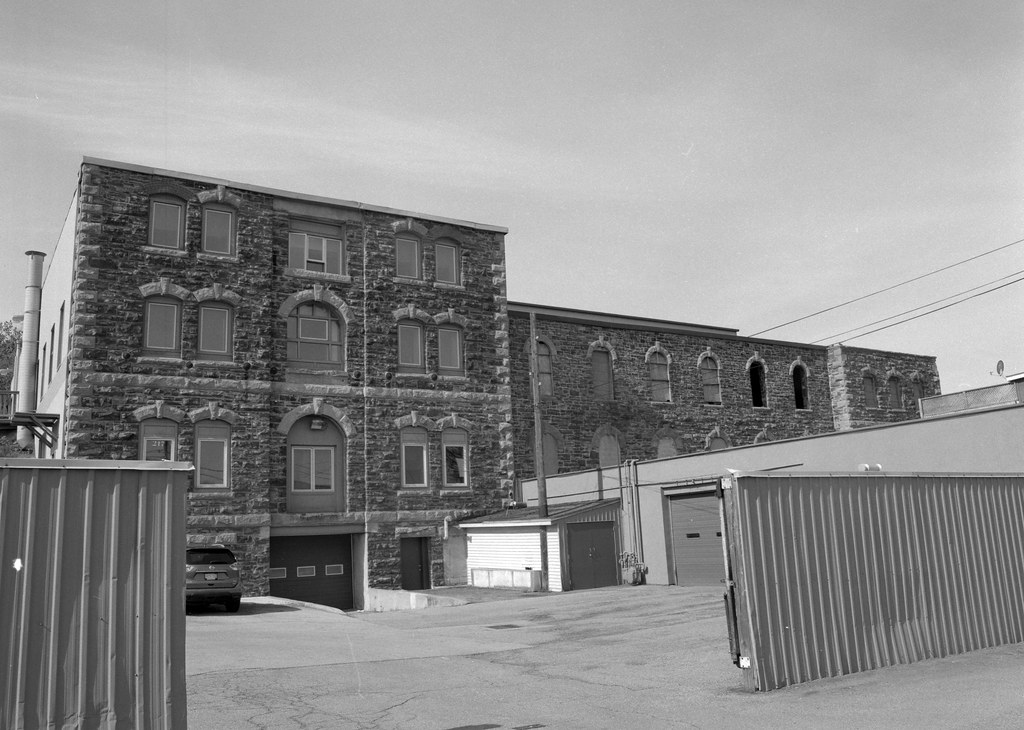

The improved canal brought a second wave of growth into the region as the industrial revolution arrived. New mills sprung up along the route, and new communities grew up around these mills. One of the first, the Welland Mill began construction in 1846 and formed the core of the village of Thorold. Founded by Jacob Keefer, the mill soon became the largest flour producer in Canada West, with enough storage to keep 70,000 bushels of wheat and 5,000 barrels of flour. Merritton turned into a new manufacturing centre with the 1857 construction of the Lybster Cotton Mill followed by the 1866 Beaver Cotton Mill. Paper manufacturing would soon follow in 1867 with the construction of the Riordan Paper Mill. This boom all thanks to the improved transport and power options provided by the second canal.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Manufacturing and Milling was not the only business to take off from the new Canal. At the different port towns booms in the hospitality industry fuelled by the need for hotels, taverns, and public houses to provide rooms and entertainment for not only the crews of the ships transiting the canal but passengers were travelling along the canal which did not want to stay aboard the cramped quarters on the vessel. Shipyards sprang up as well, initially to conduct repairs on the ships travelling across the canals and then the construction of new ships designed to travel the canal and the great lakes. The most famous of these was the Muir Brothers. Alexander Muir, a respected a retired ship captain himself established his floating dry dock at Port Dalhousie in 1850 and convinced his brothers to join the firm. By 1855 the brother’s launched their first ship, the Ayr. By 1866 the brothers operated a pair of floating drydocks and even had a fixed drydock. The Muir brothers became well known for their quality of work and ships. More and more shipyards and drydocks began to spring up along the length of the canal.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamyia-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Rollei Superpan 200 @ ASA-200 – Blazinal (1+100) 60:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamyia-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Rollei Superpan 200 @ ASA-200 – Blazinal (1+100) 60:00 @ 20C

The construction of the third canal in 1872 did not spell the end to the second canal, many businesses that had sprung up along the banks relied on the power and transportation provided by the second canal. Thankfully another route change allowed the second canal to continue operating well into the first decade of the 20th century. When the Beaver Cotton Mill burned down, it was rebuilt in the same location in 1881. In St. Catherines Canada Hair Cloth opened in 1890, and Maple Leaf Rubber opened in 1900 in Port Dalhousie. Alexander Muir passed away in 1910. However, his drydock continued operating under his family. The last ship transited the canal in 1915 when both the second and third canals were decommissioned, and the fourth canal opened. The Welland Mill, now under Maple Leaf Flour ceased operation in 1926. The Muir family sold it’s business to the Port Weller Drydock in 1953 and ceased operation in 1968. The Lybster Cotton Mill would be transformed into a paper mill and cease operations in 2002 as a Domtar Plant. Both the Lybster and Beaver Mills were restored through the early 2000s, with the industrial lands cleaned up and transformed. By 2001 the Beaver Mill reopened as a Keg Steakhouse while Lybster became a boutique hotel and Italian restaurant. The Welland Mill was also saved from demolition and in 2007 opened as a mixed commercial and residential building.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamyia-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Rollei Superpan 200 @ ASA-200 – Blazinal (1+100) 60:00 @ 20C

Today you can explore almost the entire length of the second Welland Canal. Through much of the canal water even still flows through the canal valley and the deep cut. The stone lock walls have removed the wooden doors are still intact. Other areas the canal cut has been filled in to allow for the reclamation of land in towns like Thorold. However, even in Thorold and Port Robinson, the top sections of the locks are visible. The entrance locks at Port Dalhousie, Port Colborne, and Port Maitland are all still visible. In Port Dalhousie, the lock is now an outdoor stage. Surprisingly much of the industry along the canal remains intact as well, and as I mentioned many are restored to new use, you can still see Maple Leaf Rubber, Muir Brothers Drydock Canada Hair Cloth, Lybster Mill, Welland Mill, Beaver Mill, and Riordan Mill. The best way to learn more about and explore the historical canals is to attend the Welland Canal Advocate hikes that run every month. The WCA is a dedicated group of men and women who seek to preserve and teach about the canals, and I had to honour of attending one of their hikes back in May, which was worth the drive to get out there.