Despite the setbacks of the rebellion, the reform movement was ready to move on. The radicals were out of reach, imprisoned, dead, or in exile (with the penalty of death if they should return), the moderates were now returning to the political arena many who had never run for public office before. And while Durham’s report had spoken favourable of Responsible Government and many reformers like Robert Baldwin, Louis La Fontaine, and Francis Hincks had spoken in detail to Durham. The trouble remained that even moderate reformers were still viewed through the lens of rebellion by the Colonial Office. And they aimed to use the Act of Union as a punishment on the French-Canadians by forcing total assimilation with the English language, culture, and religion. What they did not count on was French-Canadians using the union to further their own goals and secure French-Canadian Culture as being unique and different but still loyal to the Crown. The trouble would be the new model for the Provincial Parliament, while similar to the 1791 Consitution, the act changed a few things on how the Parliament operated. First, they aimed to have a limited form of cabinet rule where the Governor appointed members to his executive to work on his behalf in the Assembly. Second, the assembly would be split into two equal sections the first represented Canada East (Lower Canada) the second Canada West (Upper Canada) for a bill to pass it must be given a majority vote in both groups. To establish the new United Province, Sir Charles Poulett Thompson arrived in Canada in 1840 to take on the role of Governor-General for British North American and Lieutenant-Governor for Canada. Thompson, or Lord Sydenham, had no liberal leanings and worked under orders to assimilate French-Canada, resist responsible government and reform of any kind.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

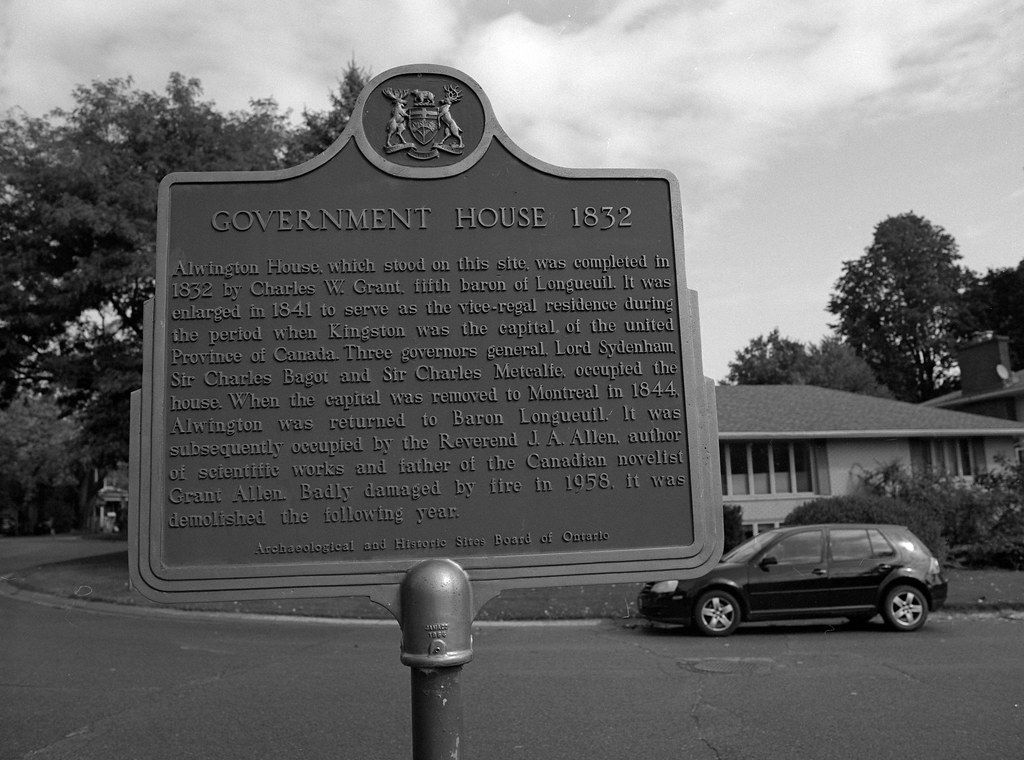

For Thompson the key to ensuring total assimilation he must send a clear message right off the start and did so with the selection of Kingston as the new capital city rather than the traditional choices of either Toronto or Quebec City. Kingston, located in the heart of Canada West, it was Anglican, Tory, and an Orange Order stronghold. As a city, Kingston was a military town home to the most extensive Naval base and garrison in Canada West but lacked any modern conveniences. No dedicated sewage or sanitation services and there were no buildings suitable to house a Parliament. Instead, the government annexed the local general hospital and converted it to government offices. Even the Governor’s residence, Alwington House, was borrowed from its owner. Lord Sydenham took his role as a suppressor of reform seriously and began to redraw electoral districts, specifically in Canada East to reduce the voting power of French-Canadians and reduce the possibility of French-Canadians being elected to the Assembly. In Canada West, Sydenham took a different approach, offering positions in the new government to men like Baldwin and Hincks. To Baldwin, he proposed the post of Attorney General and Hincks Inspector General. But two things happened that Sydenham did not consider. First, so enshrined in the idea of Responsible Government was Baldwin he would not accept the position unless he was first elected to the assembly. But the real question would be which district and seat would he run in, 2nd York was closed to him due to a strong Tory presence and the Orange Order. Taking his chances he ran in two districts, 4th York a traditionally reformed district and Hastings, winning the election in both districts. Hincks, who had won in Oxford approached Baldwin and David Wilson (of the Children of Peace) with an idea. Hincks having run a newspaper to spread the word of Responsible Government had come across an essay by a French-Canadian Reformer, Louis-Hypolite La Fontaine. La Fontaine faced severe threats in his home district of Terrebonne in Canada East, with that he wrote an impassioned plea to the voters titled An Address to the Electors of Terrabonne, Hincks proposed that La Fontaine be invited to run for a seat in Canada West. Baldwin quickly agreed, recognising the basis of responsible government in La Fontaine’s address and gave up his position in 4th York allowing La Fontaine to run with the backing of the Children of Peace, Baldwin and La Fontaine, he took the election. In the meantime, Sydenham had been moving to form a party of his own, a middle party made up of moderate conservatives and reformers who did not so much believe in responsible government but rather reasonable government. And while Sydenham did have a majority, it became clear that he would have no choice but to include both reformers and French-Canadians in the executive to form a government. Baldwin demanded that La Fontaine be involved in the Executive, going so far to threaten resignation. Begrudgingly Sydenham agreed and extended an invitation to La Fontaine and the role of Attorney General of Canada East. Sydenham’s poor health combined with the terrible conditions in Kingston saw him die on the 19th of September 1841, forcing yet another round of elections.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-400 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:00 @ 20C

The first elections in 1841 had proved one thing, that English Reformers and French Reformers worked well together and they were stronger. Both La Fontaine and Baldwin showed themselves leaders in the movement. Each man was far from their centres of support and found support in each other. Kingston did not sit well with either man for different reasons, for Baldwin, the Orange Order did their best to make his life difficult, and the language barrier proved difficult for La Fontaine, yet together they propped each other up, showing a level of unity not seen between French and English Canadians. The arrival of Sir Charles Baggot marked another round of elections. Like Sydenham, Baggot had no love for the reform movement, but he could no longer touch La Fontaine who sat securely in 4th York. Instead, he sent the Orange Order after Baldwin in Hastings. He had no desire to form a middle party; he wanted strictly loyal Tories to take the election and control the Assembly. Instead of losing a vital member of the movement, La Fontaine arranged for Baldwin to run (unopposed) in Canada East. Despite his best efforts, Baggot had to give control of the government to the Reformers, and while Baldwin and La Fontaine retained their positions as Attorney Generals but Baggot also would be forced to provide them with additional titles as Premiere. As Baggot’s health began to fail, he left the two reformers in near total control of the government. While still a small victory for the reform movement, the two men began to work on building a foundation. Baggot did remain elusive towards the idea of total responsible government but generally gave the men a free hand. Baldwin and La Fontaine set about building stronger municipal governments and providing funding for separate schools for minorities, in Canada West a French and Roman Catholic system and in Canada East an English System. What they did not realise is that their time remained short as word of Baggot’s allowance of reformers and French-Canadians did not sit well in London and the Colonial Office had already moved to replace Baggot. But before he could receive the news, he also died on the 19th of May 1843. Sir Charles Metcalfe had no intention of giving any space for the reform movement, but he wasn’t about to play his card just yet. Baldwin would advise the members of the Executive to not bad mouth the new governor Baldwin reached out to Metcalfe and offered to show the new governor how responsible could work and work well. Metcalfe did not like Baldwin from the start, and when Baldwin presented an idea to put an end to electoral violence through the suppression of the Orange Order and similar secret societies. The move angered the Orange Order, which is precisely what Metcalfe had hoped when he refused to act and wanted the Executive to create a formal bill. The Orange Order proceeded to protest outside the Parliament and even Baldwin’s private Toronto home terrorising his family by burning both Baldwin and Hincks in effigy. When the bill passed the Legislative Assembly, Metcalfe delayed. Everything came to a head, Baldwin resigned out of principle, and La Fontaine followed out of his alliance to Baldwin, the rest of the reformers in the executive did the same all but a single Tory member. And they didn’t just resign from the executive. They resigned from their appointed positions and the Legislative Assembly. Under the constitution, Metcalfe had to call elections, but instead, he suspended the assembly, used his power and governor to appoint an executive of his own and rule directly.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Knowing they would face a fight in any future election, Baldwin who was ready to drop out of politics altogether but convinced to stay by Francis Hincks made a point to reorganise the reform movement into the Reform Association. The idea was to cement the concept of responsible government under a Canadian model that could be easily understood and spoken about to all. While Reform candidates spoke on responsible government, Sir Alan MacNab managed to gather the hard-line conservatives and few Family Compact allies into a cohesive Conservative Party to challenge the reformers. Metcalfe took a different strategy and countered the reformers call for a government responsible to the electors, but since Canada was still a Province of the Empire, the government had to be responsible to the Crown. And to prove his point he remained in Kingston, laying the cornerstone to a grand Parliament Building. The plans had been in the works since 1841 under the direction of noted architect George Browne, who designed a building that occupied a full city block and designed in the neoclassical style. When elections were finally called in 1844, Baldwin wished to run in Canada West, but could not hope to run in either Hastings or 2nd York. La Fontaine resigned from 4th York and returned to Canada East, and in a grand ceremony, the men launched their campaign from Sharon. The reformers now faced an even bigger battle as Metcalfe had also gerrymandered the districts to reduce the power of reform voters and French-Canadians. The conservatives would win a majority thanks to the combination of redistricting and electoral violence. Sir Allan waited to be appointed Premiere by Metcalfe, but Metcalfe had no love of the Family Compact either and turned again to Henry Draper to take on the Premiership.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Metcalfe quickly learned that both La Fontaine and Baldwin returned to the Assembly and took any chance they could to speak on Responsible Government turning the minds of a great many moderate conservatives. Each man spoke well and made their points understood. And Metcalfe knew he could not hope to assimilate the French-Canadians into the English culture fully. He even signed a bill that granted amnesty to several rebels still imprisoned, just as Lord Sydenham granted pardons to both Samuel Chandler and Benjamin Waite. But Metcalfe’s health soon took a turn as his cancer forced his return to England. For his efforts in resisting the move to responsible government, he was awarded a peerage as a Baron. He would die on the 5th of September 1846. The Conservative Government would move the capital to Montreal a far more civilised city in Canada and much better suited for a more multicultural viewpoint, and Montreal had both an extensive French and large English Populations and the recently vacated St. Anne’s Market Building proved a valuable building to house Parliament. Much to the annoyance of Kingston, they were shouldered with the full cost of their grand City Hall when it was completed in November of 1844. And while they gained a few steps forward, they had taken a few steps backwards. But the reform association would soldier forward. But the goal of Responsible Government at least now was within their grasp.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Today Kingston is a thriving city with a rich heritage in both history and architecture. And it is littered with reminders of its small role as the provincial capital. Most notable is the Kingston City Hall, while the council did make use of the building they needed to rent out sections to various groups including the police department to pay for the structure. However, by the 1950s, the 100-year old building needed severe restoration. Efforted ended in 1973, and today the building stands at one of George Browne’s premiere works. The building is still used today at the City Hall and can be toured by the public. The Kingston General Hospital would return to its former life operating as a charity hospital by the Female Benevolence Society, and today the building remains a part of the Kingston General Hospital known as Watkin’s Wing. Plaques on the exterior of the building outline the history of the site. Alwington House returned to being a private residence, the house burned in 1958 and would be demolished a year later. The area became known as Alwington Place and grew into a wealthy neighbourhood, in 1968 Arthur Davis purchased the plot where the house once stood and built a new home, leaving the foundation of the old house as a retaining wall around the new home. A historical plaque stands nearby outlining the history of the area. Each of the three early governors are remembered in Canada, with Sir Charles Thompson (Lord Sydenham) providing the original name for Owen Sound (Sydenham) along with a street in Kingston and Simcoe, both Sir Charles Baggot and Sir Charles Metcalfe giving names to two Kingston streets. The idea of any electoral violence and gerrymandering is near unheard of in Canada. Many countries even democratic ones still face a lot of interference in their elections both within by those who want to hold onto power by any means at their disposal and without by those who wish to people in power to will be friendly towards them or turn a blind eye to their actions elsewhere. And those influences are still felt even in Canada.