There’s too much confusion; I can’t get no relief…

When it comes to photography, there is a lot of information out there, cameras, formats, film types, developer types, processes. There’s a lot, and it’s all rather complicated because some of the information dates back over 100 years. So today I’m going to do a little bit of a breakdown and hopefully clear up some of the confusion I’ve seen online as of late.

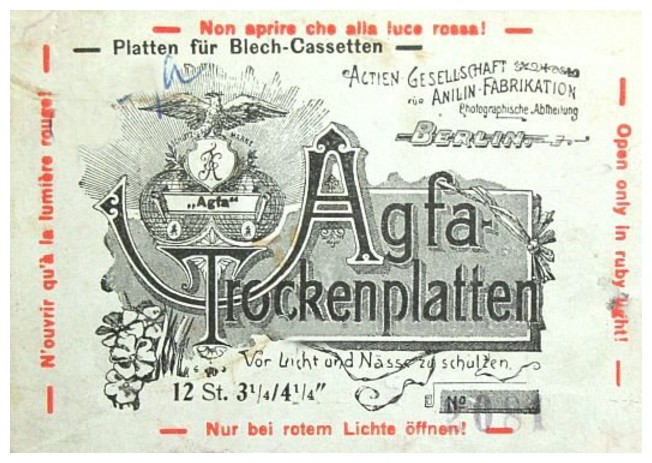

Plates

Before flexible films, there were plates. We’re talking Glass here that is sensitised and used to capture images. These plates did not conform to the standard sizes we’re used to today. And some of the cameras are still around and are used by those who continue the practice of that original photographic process, Daguerreotype. Usually, the camera is referred to as what plate size it takes. A Whole Plate or Full Plate is 6.5×8.5 inches. Half Plate is 4.25×5.5 inches, and so on down the line, the smallest plate is a Sixteenth Plate clocking in at 1.375×1.625 inches. These sizes indicate the total size of the plate, including the area that could be covered by any frame or mount the photograph, is displayed in. And while the use of the old “Plate” system has fallen into general disuse, several people are bringing back the use of dry plates in more common sizes, sizes in line with flexible sheet films. If you are interested in shooting plates, check out Jason Lane’s site, Pictographica for lots of tips, tricks, and technical details. The invention of flexible film in 1881 and its commercial success with Eastman Kodak spawned a whole new set of sizes and numbers.

unbekannt, okänd, onknown – Public domain

Flexible Films – Sheet Film

Since I started with Plates I might as well keep it big to start with, large format sheet film shares little in the general sizes with the old Photographic Plates, but like plates, sheet film is measured and indicated in inches. While many don’t consider the size in the ‘large format’ domain, for the sake of classifications, I’ll include them here, clocking in at the smallest size we have 2.25×3.25 inches along with 3.25×4.25 inches, generally these were used in the Century or Baby Graphic cameras and aren’t readily available new, but you can cut down larger sheets. For most large format starts with 4×5 inches sheets most people referred to these as Four By Five (4×5), some go 5×4, but it doesn’t matter in the end. Next up is 5×7 and 8×10. But you can get these films even bigger, anything bigger is usually classified as Ultra-Large Format going up from 11×14, not to mention stranger sizes in 7×17 and so on. While 4×5, 5×7, and 8×10 are fairly easy to get your hands on, the ultra-large formats you need to put in special orders with Ilford and Kodak.

Flexible Films – Roll Film

Okay so the first couple sections were easy, but here’s where things start to get rather messy. Flexible roll film has been around since 1881 that’s almost 140 years! So there has been a lot of different numbers and sizes to toy around with. Eastman Kodak would be the one who started assigning numbers to these roll film formats starting back in 1895 with the 101 format. These early formats are what we today consider “Medium Format” so let’s start there.

Roll Films – Medium Format

In general, terms what we consider medium format today is a bit nebulous as there is so much out there starting with the original 101 Format released by Kodak in 1895. Unlike plates and sheet film, the measurements on roll film are usually by the size of the image exposed onto the film, not the physical measurements of the film itself, edge to edge. And this is determined by the camera, but more on that later. Most people will speak measurements in centimetres or inches, rarely is the image size delivered in millimetres (but it has been). Kodak released ten early iterations of medium format films, with formats starting at 101 and ending with 119 (for my purposes today). The image size that was exposed onto 101 formats measured 3.5×3.5 inches. And even in these early releases, there were two types, roll film and film for roll holders. The largest image size of these early formats were 7×5 inches, and yes they did come that big. All these early formats were released between 1895 and 1900 and where discontinued between 1924 and 1984. 101 Format continued production until 1956 and 116 would be the last of these early formats to be discontinued in 1984. In 1901 Kodak released a new format, 120, the next in the numerical sequence started with 101. The first use for 120 film would be for snapshot photography and designed for use in the Kodak Brownie No. 2. The physical size of the film is approximately 62mm in width, with the image size being determined by the camera, the popular sizes include 6×4.5cm referred to as ‘645’, 6x6cm, 6x7cm, 6x8cm, 6x9cm and even larger. The 6cm constant allows for the 1mm rebate on either side of the frame. Kodak would continue to release more roll films throughout the rest of that first decade of the 20th Century. With formats following the numerical sequence with 121 in 1902 up to 126 in 1906. A popular format 122 produced an image size of 3.25×5.5 inches and became known as ‘postcard’ format. Save for 120, the last of these were discontinued in 1971 with 122 being the final one to go. In 1912 Kodak introduced the 127 format, a smaller version of their 120 but continuing along with the numerical sequence. 127 had the physical dimensions of 46mm in width, most cameras producing a 4x4cm image, but you also had cameras producing a 4x3cm or 4x6cm. 128 and 129 format saw release that same year, and there was even a 130 format released in 1916. Even today, you still see 127 film produced.

There are, of course, exceptions to the rule and Kodak being the Apple of the day, decided that it didn’t like having all these competing cameras and films out in the market. So they decided to release some of their old formats but on a new spool. You can tell these because they take the same final two numbers, but instead of the 1, they have a 6. Kodak released only two of these formats with 616 being released in 1931 and 620 in 1932. Physically the film is the same size at 116 and 120; respectively the spool is just thinner. The other exception to the rule is 220 film. In a nutshell, 220 film is the same as 120 film only double the length and does not have any backing paper, and mostly used in magazine type cameras that have automatic film advance, no red window.

Roll Films – Minature Format

First off, yes, Minature format, these are roll films that are smaller than Medium Format roll films. This is the format that supplanted medium format as the film for the snapshot amateur shooter, although a great many professionals began to use the format as well. The dimensions are generally measured in millimetres. It originally got its start in the motion picture field when Edison sliced the standard 70mm format in half, resulting in two 35mm width strip, add in the perforations on either edge, you get a frame width of 24mm. In 1934 Kodak assigned the digits 135 to the format, skipping ahead several numbers in the sequence, and the only time the format came close to matching the physical dimensions. 135 film came in pre-rolled, daylight loading cassettes that were loaded into the camera, attached to a takeup spool, then rewound into the original cartridge. These days we tend to refer to the format as 35mm as 135 has fallen into disuse, but is still the official format name. Most 135 cameras produce images with a length of 36mm and a width of 24mm, in the digital world this is called full-frame. However half-frame cameras produce a 18x24mm image, doubling the number of exposures on a single roll. After 135 the format numbers started to go a little squirrely and included some reuses of old numbers.

The first format to reuse an old number is 126. The original 126 format came out as a ‘medium format’ roll film in 1906 with production ceasing in 1949 and produced a 4.25×6.5 inch image, the new 126 better known as Instamatic came out in 1963. Widthwise, Instamatic is 35mm, same as 135 film, but lacked the sprocket holes, having only one per frame. Kodak intended to use 126 to show that the images were 26x26mm. Now Kodak came close with a full-frame being 28mm square and the final image being 26.5mm square. Again you see the format being close to the physical size. One of the strangest formats for the miniature category is 828. Released in 1935 it is standard 135 film without the sprockets at all and came on a spool similar to medium format film complete with backing paper. It has the same 35mm width, most cameras produced a 24x36mm image but operated like a red-window box camera. 828 format continued production until 1995 and 126 until 2008. The final format that can be classified here is APS or the Advanced Photo System which got the official format number of 240. The physical stock size is 24mm in width, again the number matches the dimension and saw release in 1996 with production ceasing in 2011. There is a lot to be said about APS, but this is not the entry for that. You might want to listen to the Negative Positives Podcast to get your APS fix.

Roll Films – Sub-Minature Format

Yes, there is something smaller, and there’s a good chance you have used one of these cameras at least once. The most notable of the sub-mini formats is 110. Again another re-introduction of a format number by Kodak. The original 110 is a medium format roll film that saw production from 1898 to 1929 producing a large 4×5 inch image. The modern 110 saw the introduction in 1972 as a smaller version of the Instamatic film and became known as Pocket Instamatic. The film came in a small drop in cartridges like its larger cousin, physically the film is 16mm in width and produced 13x17mm images. But that wasn’t all from Kodak; they had Disc film from 1982 to 1999 which used a round(ish) sheet of film in a cartridge that rotating producing fifteen 10x8mm images. Minox ‘spy’ cameras used 9.5mm film loaded up into cartridges producing 8x11mm images. And finally, the HIT format producing 14x14mm images.

Okay, so now that you’ve hopefully digested all that, you’re probably wondering what brought this post on? Well, recently a group of us film bloggers have noticed a trend that 120 film is being listed as 120mm film. A great many images are being posted on Instagram using the tag #120mmfilm. It’s also crept into descriptions of cameras and being used on commercial sales sites. Surprisingly some films have the 120mm measurement; there are 1898’s 113 (90×120mm) and 114 (120x90mm) formats. And while generally, I won’t correct the average person who calls it 120mm film, it has to be known that 120 is simply a number assigned by Kodak to the film stock because it was the next number in the sequence. I also would not do it public, that’s what direct messages are for, no public shaming here. So if you’re offering the film up for sale on a commercial site or are a business promoting your film processing, please call it 120 or simply Medium Format.

If you want to check out more of the Crusade of 120not120mm check out these other articles.

120not120mm.com

Emulsive – Rants: There’s no such thing as 120mm film

35mmc – There’s no such thing at 120mm film

Austerity Photo – It’s not 120mm Film, But it hasn’t always been 120 either

Japan Camera Hunter – 120 Not 120mm Film

Mike Eckman Dot Com – Five things that are 120mm and one thing that isn’t.

I purchased an old camera and it had film inside. I rolled it back sealed it and now I don’t know where to develop. Any help will be appreciated. Verichrome V123-6 and the spool is 4.5 inches

I would recommend sending it to Film Rescue International. They can do all sorts of older formats.