When it comes to the names of the Fathers of Confederation, those men who attended the conferences at Charlottetown and Quebec, most Canadians can only list a handful, or just one. That name is Sir John A. MacDonald. And while MacDonald certainly made a name for himself in his roll in what could almost be seen as bullying the other Provinces into Confederation, we often will overshadow the man who could almost be considered the architect of Confederation, George Brown. The eldest son of six, born to Peter and Marianne Brown on the 29th of November 1819 in Clackmannan, Scotland. George grew up among the well-to-do of Scotland’s cities and attended the prestigious High School and Southern Academy in Edinburgh. When he graduated, he joined his father in business and was welcomed into the social circles of the commercially successful. Many of his future political ideals were learned from his father. As an evangelical Presbyterian, he believed in civil and religious liberty, as well as laissez-faire economics. That is the view that economies and businesses function best when there is no interference by the government. Peter also instilled a strong belief in reform politics. But when Peter was involved in the loss of public funds in which he was found not-guilty but being unable to make up the payments due to an economic slump the Brown’s immigrated to the United States. In New York City Peter and George were moderately successful in running a dry goods store, but Peter’s attention was soon drawn to the newspaper industry. He began to write for a few British papers in the city aimed at ex-patriots before establishing along with his son The British Chronical in 1842. The Chronical provided greater coverage of political and religious news weekly. George would come to cover the political aspect of the paper and began to prefer the struggle for reform in Canada and often travelled to Kingston speaking with several key figures in the reform movement. In 1843 during the Great Disruption that saw the evangelical pastors in the Church of Scotland split and form the Free Presbyterian Church, Peter and George wrote extensively in support of the Free Church. When the Candian branch of the Free church learned this, they provided means for George and his father to emigrate to Canada.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

The Browns would settle in Toronto that same year and with the aid of the Free Church establish a new paper, the Toronto Banner which wrote in support of the Free Church. But George no longer wished to write on the religious matter and desired to pursue political news. When the Reform Society learned that George had relocated to Canada, they provided him with £250 (that’s approximately $51,000 Canadian today) of startup capital to establish a Reform friendly newspaper in Canada West. The Toronto Globe made its debut on the 5th of March 1844, Brown used the paper to promote the idea of responsible government, constitutional reform, supported reform candidates in the election, and encouraged the abolition of slavery. As a member of the Free Church, Brown despised the practice and would go on to form the Canadian Anti-Slavery Society in 1850 to provide aid for those who escaped to Canada and promote the removal of the practice across Canada and the United States. There was a dark side to Brown; he disliked the Roman Catholic Church and was not too trusting of French-Canadians. Often his anti-Catholic writings would go on to encourage and inflame attitudes leading to violent riots like the ones in Montreal in 1853. While Brown had no thought of running for public office, he did head up a Royal Commission in 1849 to investigate the treatment of prisoners in the Kingston Penitentiary. The report found rampant abuse and lead to the dismissal of the warden and earned Brown an enemy in the form of John A. MacDonald, a Kingston Conservative. MacDonald would not be the only one he’d have to face, William Lyon MacKenzie would use Brown’s anti-catholic stance to defeat Brown in the election. But Brown would win his seat, siding with the radical reform party, Clear Grits. Brown would be a perfect fit with the Grits, as many of his personal political views aligned with theirs. Such as the annexation of Rupert’s Land, secularisation of the Clergy Reserves, small government, and representation by population. By 1857 Brown had become the leader of the Grits and in 1858 when the Grits and their Canada East Counterparts took a majority of the seats was appointed as Premiere. His government lasted four days before falling in a confidence vote. Brown would go on to serve as chair of an all-party committee to investigate a way to prevent future deadlocks. And while his first solution did not pass, he wasn’t about to give up. Instead, he decided to go to England, having health issues and needing to regroup. While there he met and married Anne Nelson in 1862. The next year he returned to Canada, and just in time as in 1864, he would accept the offer of an alliance from John A MacDonald to form a grand collation to prevent the government from falling again. But his alliance had a cost, MacDonald and Cartier must seek a wider union of all the provinces in British North America, and Brown knew exactly where to look.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

At Charlottetown, George Brown would be in his element. He had been working on a grand constitution that would see the creation of a new nation that would be self-governing, semi-autonomous without cutting ties with the British Empire. He spoke at the conference for two days in public and met privately with several other delegates, including Henry Pope of Prince Edward Island to sell his idea. Pope would go on to be an ardent supporter of Confederation and even left the provincial government of the island when they refused to pass the resolution. At Quebec, Brown would side with George Cartier to ensure that Canada East and Canada West would be separate provinces in the new Confederation as they both felt each had undue influence on the other. He would gain his idea of representation by population as a way to assign the number of seats in the House of Commons. But his idea of an elected Senate laid out the same way did not fly. And when the Quebec Resolutions were adopted, it would be Brown who presented them before the Colonial Office at the end of 1864. But his participation in the Coalition ended in 1865 over an internal dispute over leadership. But even though he ceased to be a part of the government, he did not stop his support of Confederation, speaking at length in favour of the move during the debates over adopting the resolution. Brown would not be present at the London Conference. During the first federal election, in 1867, he ran for a seat in the House of Commons as well as running for a seat in the Ontario Legislature. In Ontario as leader of the Liberal Party (the name adopted by the Clear Grits in 1867), he would have been Premiere. However, he lost both elections and decided to retire from politics.

Contax G2 – Carl Zeiss Biogon 2,8/28 T* – Kodak Kodachrome 64 @ ASA-64 – Processing By: Dwayne’s Photo

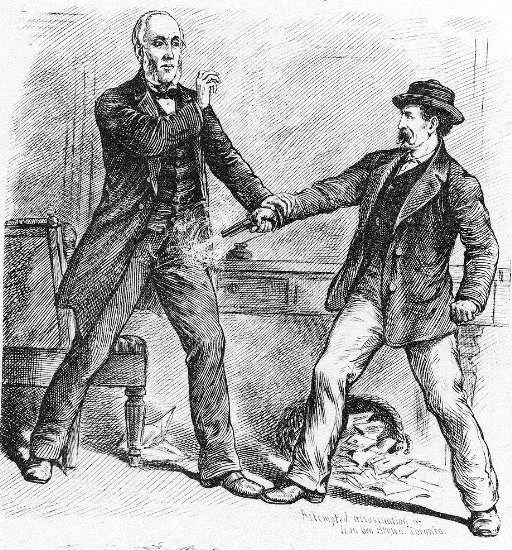

And while he retired officially from politics, he didn’t stray too far from them either. He provided much-needed support for members of both the Ontario Legislature and the Federal Government. He also spent his time with his newspaper and expanding his cattle farm at Bow Park near Brantford. In 1874 he would be appointed at a Senator by his former right-hand-man now Canada’s second Prime Minister, Alexander MacKenzie. The same year he began construction of a grand home, Lambton Lodge, in Toronto. On the 25th of March, 1880, a dismissed foreman, George Bennett, stormed into Brown’s office at the Globe. Bennett intending to kill Brown aimed his gun, the two struggled, and the gun discharged into Brown’s leg. Bennett would be arrested the same day on the charge of attempted murder. As Brown languished at home, an infection would turn the wound gangrenous and on the 9th of May 1880 Brown would slip into a coma and die. Bennett would be charged with murder and during his defence pleaded he would not have done such a thing, but he had been drinking at the time. Bennett would be hanged for his crime. Brown’s remains are buried at the Toronto Necropolis.

Julien, Henri, 1852-1908 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

For the amount of work he did for Confederation, Brown received the little accolade in his day having left government by the time Confederation had been completed. And even still today there is little to remember him and his role in the whole plan, being overshadowed, like the other fathers of Confederation by Sir John A MacDonald. That being said, Brown is still pointed to as the progenitor of the modern Liberal parties in Ontario and the Federal Government, and both still use the term ‘grits’ as a nickname. A statue of Brown stands in front of the Ontario Legislature in Toronto. Lambton’s Lodge would go on to house the Coulson family until 1916 and then become offices of the Canadian Institute for the Blind until 1951. By that point, the lodge was in desperate need of restoration, and after being named a historic site in 1974, Ontario Heritage Trust stepped in and began the work. In 1989 it reopened at the George Brown House and served as an event space, and has a collection of some 2,000 books that once belonged to Brown. Bow Park in Brantford still operates today but as a Seed Farm, and his newspaper The Globe, absorbed the Mail and Empire in 1936 to become the Globe & Mail which still operates today. Toronto’s’ George Brown College is named for the elder statesman. And while Brown never had any major scandals in his pocket, his distaste of the Roman Catholic can be seen as bigotted and his view of French-Canadian as racist. His model of representation by population has grown these days into a major split in Canadian unity as in Federal elections are often decided in Ontario leaving voters out in Alberta and Saskatchewan with a distaste of the west. And yet, without Brown, like MacDonald, there would never be Canada as it stands today.