If you ever get the chance to visit Quebec City, take the opportunity. Not only is it one of the most beautiful cities in Canada, but it also intersects with many of the significant events that would go one to shape Canada throughout history. From the establishment of the first French settlement in what would become Canada, to the fall of French Rule on the Plains of Abraham in 1759. The Quebec Conference of 1866 to the other Quebec Conferences at the climax of the Second World War that planned out the invasion of fortress Europe. While often overlooked or merged with the Charlottetown Conference, Quebec would form the framework out of the foundation. I see it as a far more critical conference in the drive towards confederation, and many of the ideas founded by these men still are enshrined today in the Canadian government. The purpose of a second conference came out of the first, and this time the Canadians agreed to play host in their acting capital of Quebec City. After the Montreal riots, the provincial capital had hopped around again from Montreal to Toronto to Quebec City all while the Parliament buildings continued construction in Ottawa on old Barracks Hill. Ottawa had been chosen as the final capital back in 1857 and suggested by George Cartier. Time would not be on the Canadians side as they had plenty to do before the conference opened. Chief among them was creating a ‘facebook’ a deck of thirty-three calling cards that had a photograph but the name and position of each of the delegates. Where Charlottetown had been the sales pitch, Quebec was banked at being the working lunch.

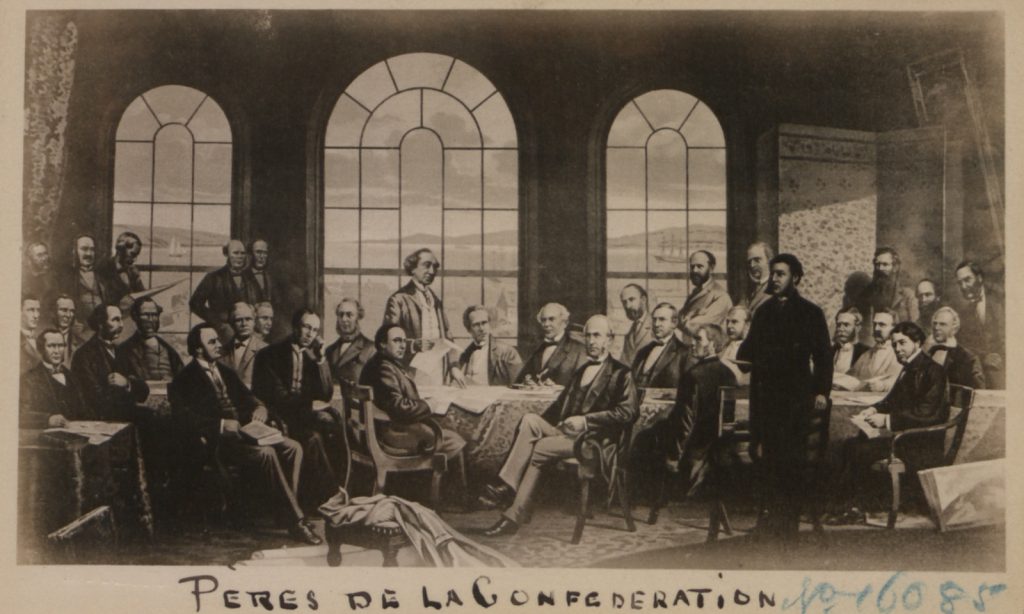

Joseph L. Pinsonneault [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The Conference opened on the 10th of October 1864 with most of the work being conducted at Chateau Haldimand the 1786 castle which served as both a hotel for the delegates and the seat of the Provincial Government. In addition to the representatives from Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. Newfoundland volunteered to send a pair of observers. As they had not attended Charlottetown, they opted to observe the conference instead and from there chose to join the union. The first hurdle to be overcome would be the style of the union. MacDonald favoured the idea of a pure legislative union, where Canada would be a country governed by a single Federal Government. MacDonald’s reasons were clear. He defended the position by looking to the ongoing American Civil War, stating that the war was a result of a weak central government. And while the model would have worked if there had been a single culture in the union, most of the others feared that the Anglican English culture would steamroller their culture. Men like Cartier, Tupper (Nova Scotia), and Tilley (New Brunswick) feared the loss of culture. Even George Brown thought that such a move would see too much influence from the Roman Catholic French culture. On the opposite side was a federation where there was a single weak or nonexistence central government with all the power resting with the Provincial governments. That would not fly either. A compromise would have to be reached in a Federal Union where power would be distributed fairly or shared. At the top remained the British Parliament which maintained control over changes to the Constitution and Foreign Policy for Canada. The Federal Government would deal with trade, good government, law, order, and currency. The Provincial Government handled municipalities, transportation (roads and canals), education and culture. Shared items such as taxation and immigration would be shared between the Federal and Provincial governments. Further to help ease tensions, the Province of Canada would be split along historical lines. Canada East reclaiming the historical title of Quebec. Canada West took the name of Ontario. The name coming from two indigenous sources skanadario the Iroquoian word meaning “beautiful water” or ontarí:io from the Wyandott meaning Great Lake.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Rather than reinvent the wheel, the government structure used the Westminster Model found in the British Parliament, and enshrining the tenants of Responsible Government of the Baldwinite model. An elected assembly, the House of Commons and the country divided up into electoral districts or ridings. And each province assigned the number of ridings based on population. George Brown championed the representation by population. Of course, this meant that the larger the population, the more influence they had in the House of Commons. Which meant that Ontario and Quebec held the most significant sway as they were the most populous of the Provinces. While not everyone agreed, it seemed the best model to avoid any potential deadlock, and since it was a single house, only a single majority would need to be reached. The party that received the highest number of seats would form the government, the leader of the party would be the head of government titled the Prime Minister and they would choose their cabinet from the elected officials. An upper house would also be created, in Britain, this was the House of Lords, but since Canada had no nobility, the title of Senate was chosen. Again Brown championed the idea of having an elected Senate with the representation by population model applied. Thankfully this was not agreed to, MacDonald would defend the idea that the Senate would be a sober second thought, free from the machinations of democracy. An elected Senate would be responsible to the people who had elected them. The senate was to be a check against Democracy run amuck. Senators would be appointed, and a fixed number of seats per province granted to allow for equality. And finally, there was the Crown through their vice-regal representative, the Governor-General. The Provincial governments would be consolidated to a single elected Legislative Assembly (or Provincial Parliament) headed by a Premiere and their cabinet. Gone was any legislative council, and a vice-regal representative in a Lieutenant-Governor would be appointed as the Crown’s representative.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta AF Zoom 35-70mm 1:4 – Rollei RPX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. H 18:00 @ 20C

With the two major questions out of the way, the delegates sat down to discuss smaller items. The seat of government was quickly agreed upon being in Ottawa for the same reasons it was chosen for the Provincial Capital. It sat nearly in the centre of the Union, it was tactically sound and easily defensible, and any future inter-continental railway would run right through the city. Also since the new Parliament buildings were under construction, the needed expansions could be made to support a House of Commons and Senate Chamber, originally intended to be the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council chambers. It was also agreed to construct an intercontinental railway and promises to begin expanding the union out into Rupert’s Land and eventually to British Columbia. Thomas D’Arcy McGee ensured that religious minorities had the right to a separate education system, such as the Roman Catholics in Ontario. Finally, the whole matter would be codified into seventy-two individual resolutions. These Quebec Resolutions would form the backbone of a new Canadian Constitution. And it was something new, in the past Imperial Constitutions such as the 1791 Act, the 1840 Union Act, and even granting responsible government had all been done to further imperial interests. The Quebec Resolutions gave allowances for both local interest and self-determination and maintaining imperial ties and interests. It did not seek to assimilate; it respected the culture, language and religion of all who came under the union. It showed strength in compromise, unity, and diversity. The Fathers of Confederation were rightfully pleased, and it was George Brown who took the agreed to resolutions to London after the conference ended some fourteen days later. The office agreed as did Parliament, and a draft bill was drawn up and prepared. But they still needed to pass a vote in the Provincial Parliaments, and the separation of the Canadas also required to be sorted out. But now the pathway was clear.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Portra 160 @ ASA-160 – Processing By: Burlington Camera

It is amazing at how much was achieved in those fourteen days. And while not all agreed that the time was long enough, and true there were more questions yet to be answered. You can’t help but be amazed at the achievement. Near entire independence, achieved not through violence but measured discussion and compromise. An Imperial government was willing to move with the times and willing to accept a plan. And while in 1864 there were still things that needed to be done but today we at the end of history know that they succeeded. The shadows of the Quebec Conference still come up today. With the ongoing fight between some provincial governments and the federal government over climate change taxes with words like national interest being tossed around. Or the cutting of city councils by the Provincial governments and claiming that it’s against the constitution. And trust me, the Canadian constitution is not an easy read, but I managed to pick through parts of it to ensure my correctness. And while the Constitution or British North America Act has changed since 1867 at the core, it remains the same document. Today much of Old Quebec City stands as a national historic site. Chateau Haldimand would be demolished in 1892, replaced by the grand railway hotel Chateau Frontenac. A second location connected to the conference, Parc Montmorency, opened as a public part in 1894 after the last government building saw demolition in 1883. Although as of 2019 it was undergoing extensive restoration work. Monuments and statutes to all who were involved can be found around Canada, and many would go on to be involved in Confederation and the first Canadian Parliament. But that is a story for another day.