The history of Ireland is a long, complicated, and bloody one. And it is worthy of a project of its own, and I’m sure if I lived in Ireland, I would probably be already have completed such a project. But this is a Canadian History project, yet during the mid 19th Century in a strange twist the history of Irish independence intersected with that of pre-confederation Canada. Ireland had, since the Norman invasion of 1169 been a nation under occupation. And while the ancient history of Ireland stretches out before that date, it seems like the right point to start. Further degradation of the Irish culture came in 1542 with Henry VIII’s declaration as he appointed himself as King of Ireland. And while the Irish had fought back against the English encroachment, the English had all the tools needed to suppress different cultures that didn’t fall in line. Between military might, reduction of minority rights, and the General dislike of Roman Catholicism by 1691 most of the island was under the control of loyalists; these English landlords owned much of the island. Just under the surface of control simmered revolutionary sentiment, and in 1791 a group calling themselves the United Irishmen formed. They often met in private to discuss the means to remove British rule from the Island. The group consisted mostly of non-Anglican Irishmen, Roman Catholics, Presbyterians, and Baptists. Together they ran illegal hedge schools to ensure their children were brought up in their traditions and learned the history of the island. They petitioned the government to allow Roman Catholics to vote and hold public office at least in Ireland. And while mostly peaceful, some within the group desired direct action. Some made contact with France, itself at the start of a Revolution, and invited them to invade the island. The invasion force would never reach the island, prevents by storms and the Royal Navy it would be enough to for the English government to clamp down on the United Irishmen.

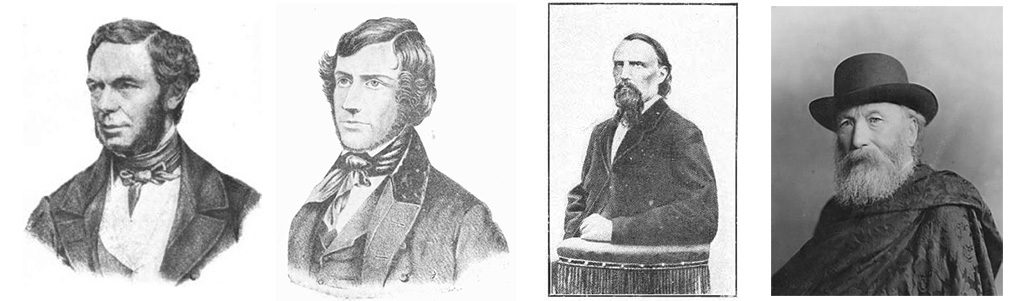

Martial Law was declared on the island in 1797, and the authorities would arrest, destroy, and kill anyone connected to the group, hoping it would keep the lesser revolutionaries quiet. The violent suppression did the exact opposite, and on the 24th of May, 1798 open rebellion seized Ireland. The rebels hoped to sized Dublin, but spies in their midst reported the plan to the British, and they were able to secure the city before the action took place. But it succeeded in the rural areas as Irish rebels employed guerilla tactics which continued to baffle the disciplined British Army. Both sides committed what would amount to war crimes throughout the rebellion, and by the 24th of October, it had all by died out, with only a few pockets of resistance remaining. In response to the uprising, the British Parliament decided to unite Ireland with the United Kingdom, signing the Act of Union in 1801. And while they promised Catholic Emancipation, it never materialised. The English feared the undue influence of Roman Catholics on Ireland. It also didn’t help the cause of the United Irishmen as the government invited Presbyterians to join in the leadership of the island, driving a wedge between them and the Catholics. And while the United Irishmen all but dwindled out, another group, the Repeal Association took up the cause. But the Association worked only in the political arena to regain independence through the ending of the 1801 Union. Michael Doheny, John Mitchel, John O’Mahony, and James Stephens would all join the association, many having parents who participated in the 1798 uprising. But they soon found the pace of the group far too slow to achieve their goals. Together they formed a splinter group, Young Ireland. The movement would spread the word of Irish independence through public meetings and a newspaper, Nation, in 1842. They called for more direct action, and even open revolution. They were joined by a strong supporter of Irish independence, Thomas D’Arcy McGee who had returned to Ireland from the United States who loaned his skills as a newspaper editor to Nation.

Nikon D70s – Tamron SP AF 11-18mm F/4.5-5.6 Di-II LD Aspherical

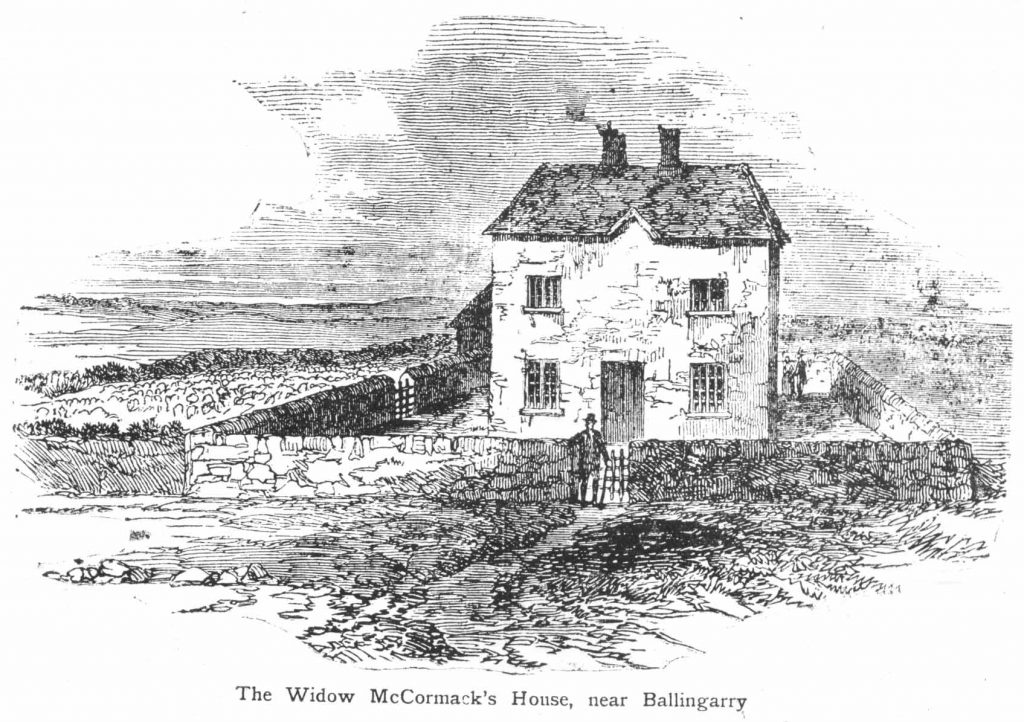

1845 brought the worst disaster ever experienced by Ireland in the 19th Century, the Great Famine. The form of blight, Phytophthora, attacked and killed off much of the island’s potato crop. While it did not affect the rich nor the vast amounts of grain and meat being exported to England, the poor were hit the hardest. This was the moment Young Ireland had been waiting for, the calls for revolution spread, many of the island’s poorer residents would flee to the United States or Canada. But Young Ireland decided to incite revolt, blaming the continued blight on England as a way to pacify the island. And on the 29th of July 1848, the Young Ireland movement clashed with members of the Royal Irish Constabulary at the farm of Widow McCormack in Wexford. It did not end well for the movement, most of the leadership arrested and executed, warrants issued for those who escaped. Michael Doheny and Thomas D’Arcy McGee fled to the United States where they were welcomed as heroes. James Stephens and John O’Mahoney would go to Paris and lived in poverty. But they did not waste their time, earning money through teaching and translation. But they also joined many of the secret political societies that populated Paris, learning how to organise and the fine art of conspiracy and intrigue. O’Mahoney would immigrate to the United States in 1853. Unknown at the time to O’Mahony was that during the famine in addition to the nearly one million dead, another million had fled to the United States. The sudden influx of immigrants who had few skills beyond basic farm labour and many who could not speak or understand English created a wave of anti-immigrant fever in the land of the free. It also did not help that most Americans had no love of the Roman Catholic Church and most of the immigrants were staunchly Catholic.

Michael Doheny’s The Felon’s Track 1849 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Collectively called the Know-Nothing movement spread vicious rumours that the Irish were little more than a secret army ready to at a word from the Pope rise up and take over. They believed that the Pope would then reform the United States into a new Roman Catholic Nation and establish the second Vatican in Cinncinatti. It was, of course, nothing but rumour but it would be enough to see anti-immigrant violence and force many of the Irish to gather together in small enclaves where their culture, language, and traditions could be practised without threat. When O’Mahony arrived, he felt that the insular nature of the Irish-American diaspora could be used to further the cause of Independence. Along with Michael Doheny began to form various Irish organisations centred mostly around New York City where a great deal of Irish lived. It wouldn’t be until 1857 that he had decided to promote the idea of Irish Independence openly, and in a letter to James Stephens, who was still in Paris, recommended that he return to Ireland to form a sister group. A year later twin groups, in American the Fenian Brotherhood was officially formed and in Ireland Stephens formed the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The term Fenian harkens back to the Irish legends of old, precisely that of Fion Mac Cumhaill, a warrior of exceptional standing in the Irish mythos. In English, we better know him as Finn Mac Cool. Using what he learned in Paris, O’Mahony set up the brotherhood to be a secret society, as the number of people increased, so did their knowledge of the overall plan. The further away from the centre, the less the person knew, that if any were captured, they only knew the person directly above them or within their circle. And O’Mahonny would be elected President or Head of Centre. The plan was simple, raise awareness for Irish independence in the United States and raise funds to be channelled to the Irish Republican Brotherhood to help purchase arms and ammunition to finance a revolution. But everyone had their ideas on how things should happen, and a rift grew between Stephens and O’Mahoney, and even with the Fenians, different wings were forming.

Nikon FA – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – SPUR HRX (1+20) 9:30 @ 20C

Throughout the remaining 1850s membership in the brotherhood took a nosedive and money sent across to the IRB faltered. It all changed when the Civil War opened in 1861, and many within the Brotherhood feared the conflict would spell the end of the Fenians in North America. Irish of all walks of life moved in enlist on both sides of the conflict, eager to prove their loyalty to their adoptive nation. And the Irish proved their worth, often being used as front line troops, cannon fodder if you will, yet among the Irish fighting the Fenian cause spread. Recruitment would skyrocket. In some cases, Fenians on opposing sides would arrange for nightly meetings, choosing a hidden location between the camps with sentries at either end, during these meetings the war was not discussed and both sides would return to their camps unharmed. O’Mahoney, who held the rank of Colonel during the war would resign his commission to work on the Fenian cause full time. By the end of the American Civil War membership in the brotherhood was at its peak and many looked upon the vast numbers of now training and battle-hardened veterans with little to put their training towards. While O’Mahonny wanted to continue along the same course as before, others were making different plans. Stephens encouraged that this new Fenian army could be transported across the ocean and invade Ireland in the name of independence. And in the United States, O’Mahonny’s chief opponent John Roberts had a different idea. Roberts suggested that they invade and hold key cities and sections within British North America. The idea was the hold them as ransom and traded them back to England in exchange for Irish independence. Stephens thought highly of the plan and officially declared his favour of Robert’s plan. And while things in North America were coming to a head, it seemed the next decades were going to either make or break the Fenian Brotherhood.

Nikon F5 – AF Nikkor 50mm 1:1.4D – Kodak Vision3 250D @ ASA-250 – Unicolor Rapid C-41 Kit

Today there is much in Ireland to remember the uprisings of 1798 and 1848. The farmhouse where the Young Ireland Uprising in 1848 remains a National Historic Site and is known as the Famine Warhouse 1848. But the history of Ireland continued down a bloody path through the Easter Rising of 1916, the civil war that followed through the Free State, Republic and the Troubles that only ended in 1998. Locally, the Great Famine is remembered in Toronto’s Ireland Park at the foot of Bathurst Street in the shadow of the old Canada Malting Company Silos. It is also worth noting that the 1840 Act of Union which joined Upper and Lower Canada after our civil war in 1837-8 looked and felt the same as the 1801 Act that joined Ireland to the United Kingdom. In both cases, they used it to punish the perceived perpetrators, the 1801 case the Irish and in 1840 French-Canadians. You have to love the cyclic nature of history.

1 Comment