In the grander scheme, the Battle of Ridgeway gets all the glory when it comes to the limited history of the Fenian Raids of 1866. And yet a second skirmish took place almost instantly after the one at Ridgeway. The sad fact is that both battles could have been avoided and maybe the whole matter could have been better remembered. But to understand where the Battle of Fort Erie came from, we must first go back to Port Colborne, where we split off last week on the 1st of June 1866. Lieutenant-Colonel John Stoughton Dennis felt left out, a blow to his fragile ego. Despite being the district militia commander he had been superseded by Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker of Hamilton’s XIIIth Battalion Volunteer Militia of Canada who was in equal in rank, but senior in commissioning date. And when the British commander, Lieutenant-Colonel George Peacock ordered Booker to take the XIIIth and the Queen’s Own Rifles to Stevensville and for him to remain at Port Colborne with Captain Richard King and the Welland Field battery to defend the lower Welland Canal.

WJ Thompson [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

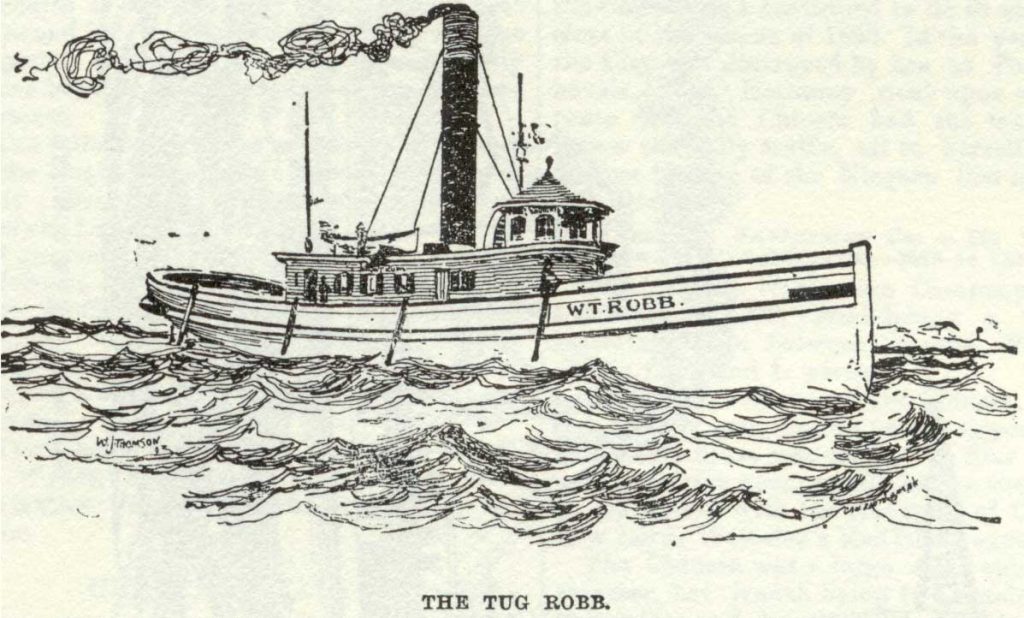

The trouble was that Dennis felt the British were purposefully holding the Canadians back from a glorious victory, trying to keep that to themselves in a swift defeat of the Fenians. Dennis had gotten word that the Fenians were nothing more than a drunken rabble at Black Creek and the village of Fort Erie stood open for recapture. Dennis believed if he could position a force at Fort Erie, Booker could convince Peacock to move on Fenians and push them towards the village and catching the Fenians between the two forces. Peacock’s Aide-Du-Campe, Captain Atkars, who had been sent to Port Colborne to ensure the orders were followed agreed with Dennis and felt that the Canadian’s intelligence was correct. Atkers and Dennis would send their plan via telegraph to Peacock at Chippawa. When Dennis failed to convince the Grand Trunk Ferry, International to come to Port Colborne and transport them to Fort Erie, Dennis reached out to his friend and fellow militia colonel, Lachlan McCallum. McCallum had a small force, the Dunnsville Naval Brigade, along with one of the fastest tugs on the great lakes, the W.T. Robb. And along with Captain Richard King and the Welland Field Battery departed for Fort Erie, leaving Booker to deal with any fallout from the action. They would have no idea until later that Peacock sent a reply overturning the plan and reaffirming his original orders to stay in Port Colborne. Booker would have no choice but to confirm his orders and march into infamy.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Despite being built for the lumber industry to pull barges, the Robb was a sturdy ship and fast. McCallum had initially wanted to arm the tug, but the government had denied the request. And Dennis had been partly right, the small garrison of Fenians at the old fort were quickly overwhelmed and forced to surrender. The militia having no way to secure their prisoners stuck them in the hold of the Robb. Having a limited number of troops decided to arrange them in two different lines to protect the two obvious roads which any retreating Fenian could use. Across Niagara Street, Dennis placed the Dunnsville Naval Brigade, and across Murray Street perpendicular to the Naval Brigade, he placed the Welland Field Battery. The Robb remained berthed at the foot of Murray Street. Despite being an artillery unit on paper, the Welland Field battery had none of their four field guns present, they were probably still in Hamilton, rather than having been brought to the front by the XIIIth. Both sides were armed with nothing more than small and personal arms, single-shot Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles or obsolete Victoria Carbines, conversions of older arms to modern percussion cap locks. But despite having the modern technology to send messages near-instantly using the telegraph, Dennis would hear nothing from Booker or Peacock, the lines around Fort Erie remained down. But the noise from Ridgeway must have carried to the village, being only 11 kilometres away, Dennis was sure that the Canadians had achieved victory and any retreating Fenians would be on the run and demoralised.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

What Dennis did not realise was that the army that now marched towards the village was nearly at full strength. O’Neill had been fighting a loose battle in troop retention, and despite having a strong force on his initial landing, his numbers were gradually going down. It didn’t help that any reinforcements had been stopped as the USS Michigan (15) along with smaller gunships now patrolled the river keeping any more Fenians from crossing. Despite everything, he knew he would have to hold the position and wait for the other invasion forces to establish control and wait for orders. He ordered the men to round up any prisoners and march back to their beachhead at Fort Erie. Dennis did not have the men to establish pickets to sound an alarm or give a report on the enemy strength. So when the forward Fenians scouts ran into the Canadians, they threw everything they got into them. The Canadians returned the favour. Dennis, however, did not look too well on the massive Irish army marching into view. O’Neill’s troops fought to win, and the Canadian line collapsed. Dennis ran, ordering the Robb to cut their lines and take the prisoners and the tug out of range. With Dennis’ departure, command on the ground fell to Captain King, who managed to regroup some troops at Catherine Street, while some troops took cover in the nearby Lewis house. With the support of King, the Canadians again fought until they couldn’t, and when King took a bullet to the leg, he threw himself in the river, and the line collapsed. Only those in the Lewis house maintained their fire until the Fenians threatened to burn the house down and they surrendered. McCallum aboard the Robb, at significant risk to himself, his surviving crew and the ship sailed further upriver and picked up the few survivors they could, then under fire heading back to Port Colborne. Captain King would be fished from the river by the Fenians and quickly slipped across the river to Buffalo for medical treatment. The militia soldiers joined their fellow Canadians at Fort Erie under guard, and the officers joined O’Neill at his headquarters in Fort Erie. While the officers enjoyed a meal with their captors, the enlisted men endured a cold night with meagre rations shared by the Fenians. O’Neill seemed interested in the size of the British force at Stevensville and its makeup as well as the situation with the prisoners held in the Robb’s hold. He seemed in better spirits when the Canadians assured him they would be well treated and very much alive.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

At Port Colborne, Colonel Booker, having returned from his defeat and retreat from Ridgeway was at whits end, he found himself in command of a vast militia force that had gathered there over the course of the day. But he could barely take charge of his troops. And many junior officers began to take matters into their own hands and deploy patrols out into the area, even the shattered Queen’s Own Rifles joined in the patrols. It did not help matters when Atkers returned, having escaped Fort Erie, with word of Dennis’ defeat at the village. The only high point would be the arrival of the Robb with prisoners. O’Neill, now in full control of the village and realising that he now faced a large force of British regulars, Canadian Militia, artillery, and cavalry, knew he had no choice but to retreat to the United States and hope for success in other theatres. He ordered the prisoners be brought up from the Fort and the tugs and barges brought to the Catherine Street dock. The Canadians were lined up on the pier and feared their execution as the Fenians lined up opposite them. But O’Neill addressed them and informed them they were now released and had won the day. They boarded the ships and headed back to the United States, but they never made it, O’Neill would be arrested mid-river by the Michigan. For Dennis, having fled the fight, he took shelter in a barn fearing that Fenian patrols would be out to round up the militia. When the barn’s owner discovered the colonel, he invited him up to the house for a meal. Then after shaving his mutton chops and trading the uniform for civilian clothes, Dennis set out for Stevensville arriving just as the sun was rising on the 3rd. He began to seek out a person whom he recognised, finding one in George Dennison. And while it took some time for Dennison to recognise Dennis eventually acknowledging the voice. Dennison brought Dennis to Colonel Peacock. Peacock had some idea of what had transpired throughout the 2nd and now realising what was taking place he began to order his troops to deploy. Dennison’s troop would ride to Fort Erie, finding the prisoners released and the Fenians nowhere to be seen. By noon the village had become an armed camp, even the Robb would return this time armed with a single nine-pound cannon on her deck and patrolling the shore and the lower Welland Canal.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

By the end of July, it seemed the Fenian threat against the Niagara region was at the end, and the militia would be released and returned home. For many, despite the failures at Ridgeway and Fort Erie, the men of the Canadian Militia returned to their homes, heroes. Some communities even authorising medals to be awarded to the militia troops. But the ghosts of the two conflicts would go on to haunt the two Canadian commanders. Alfred Booker would face criticism from within the XIIIth. Two junior officers approached a freelance journalist to tarnish his character. Similarly, when Captain King returned to Port Robinson after recovering from his wounds in Buffalo, he began to speak publicly against Colonel Dennis. Both men would call for a court marshall to clear their names. The trouble was that the Canadian government wanted to sweep the twin failures of the militia under the rug, and both men would be cleared of all wrongdoings, and the matter was forgotten. Booker would resign, retire and move to Montreal. Dennis would return to surveying work and end up in the Red River Colony during the rebellions of 1869. O’Neill would be acquitted of all charges and return to lead the Fenians two more times throughout the raids against Canada. But he would not have a second Ridgeway, raids in 1870 resulting in the Fenian defeat at Trout River and Eccles Hills showed the increased training and more targetted training of the Canadian Militia proved that they had learned from the failure of Ridgeway. O’Neill was again arrested and released. His final action leading a Fenian action took place in Pembra when a Fenian Force captured a Hudson Bay Company Post. While they believed they were in Canada, in reality, Pembra was in disputed territory and was actually in the United States. O’Neill would again face arrest and release. But the Brotherhood had fallen out of favour with the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1867 and collapse, disbanding in 1880. O’Neill would go on to lead a group of Irish into Nebraska establishing a colony and the city of O’Neill 1874. The cut off in 1867 didn’t end Irish revolutionary movements in the United States, Clan Na Gael would be created to support IRB actions in Ireland from the United States better. And while the Clan suffered the same fractious nature of the brotherhood they were held closer to account by the IRB, they would go on to hide revolutionaries in the United States during the bombing attacks of the 1880s, and into the 20th-Century the acted as a go-between between Irish rebels and Germany ambassadors in the United States. When the Easter Rising took place in 1916 and the subsequent civil war most of the funding came from Clan Na Gael. In 1922 the Irish Free State would be granted Dominion Status which would cut ties with the United Kingdom establishing the Irish Republic in 1949. Trouble remained common on the emerald isle as the late 20th-Century was a time of strife and violence as the split between Northern Ireland which remained a part of the United Kingdom and the southern Republic. It wouldn’t be until 1998 with the Good Friday Agreement and the 2005 St. Andrew’s Agreement would put an end to the violence and both parts have learned to live together. And yet the shadow of violence again is thrown in the uncertainty with Brexit.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Canadian acceptance of the Fenian raids is as complex as the history of Irish independence. It wouldn’t be until 1890 that any formal recognition of Canadian war dead took place, first honoured on the 2nd of June that year, Decoration Day would honour the war dead of the Fenian Raids, Red River Rebellion, and North-West Rebellions. And still, it wouldn’t be for another nine years before the government authorised the Canadian General Service Medal. Like the British General Service Medal, surviving veterans would have to apply to the government for the award. The Lime Ridge Monument would be raised on the University of Toronto Campus that same year. Decoration Day would continue to serve as the Canadian day of remembrance and would go on to include those who served in the Second Boer War and The Great War. In 1931 Remembrance Day would become the official day of remembrance for Canadian war dead and the date set to the 11th of November to coincide with the end of the Great War. And while the Boer War would be included in the day, the Fenian Raids and the Rebellions were quietly dropped. But Decoration day is still observed but in a small unofficial capacity. Today there is little left to remember the battle of Fort Erie. The W.T. Robb would return to service as a lumber barge tug but would be stripped of her engine and left to become the foundation of a break wall in Toronto sometime in the 1890s. Her hulk remains in that service near Kew Beach in Toronto. There are no plaques and markers in the town of Fort Erie to commemorate the skirmish. However, both battles are mentioned in detail in the Museum at Olde Fort Erie. The Lewis house would become the Ontario Bakery, and the original house would be demolished in the late 20th-Century, the current building sits on the foundations of the Lewis House. Although the building now stands empty and up for sale. I would be remiss in not mentioning that one British soldier lost his life during the Niagara raids, Corporal Carrington died of heat exhaustion in Stevensville on the 2nd of June and his grave is located in the churchyard of St John’s Stevensville. While the Fenian Raids as a whole remains a largely forgotten part of our history unless you have some direct connection to them as being a member of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry or the Queen’s Own Rifles, it is still that weird moment where Canadian History and Irish History intersected. And while the raids did little to help Irish independence having a common foe in the Fenians would go on to further bring the Province together in some form of national unity that would help Confederation during the London Conference of 1866.