While the idea of cutting a channel to safely carry cargo and people across the Niagara Penisula was not a new one by the time William Hamilton Merritt came along and pushed the idea forward to completion, Merritt is the one credited with the concept. William’s father, Thomas Merritt served under Sir John Graves Simcoe in the Queen’s Rangers during the American Revolution. After the war ended Thomas and his wife Catharine Hamilton settled in Saint Johns, New Brunswick for some time. But the call of home beckoned and the two returned to Bedford, New York. In Bedford, on the 3rd of July 1795 that their son, William Hamilton Merritt was born. But the United States remained an unfriendly territory for a Loyalist. Thomas, using his connection to Simcoe and Simcoe’s position as Lieutenant-Governor of the newly created Province of Upper Canada to petition for a land-grant. The Merritt’s moved to a farm on Twelve Mile Creek forming the core of Loyalists forming the core of the settlement known as Shipmans Corner. While not part of the upper crust of colonial society, Merritt’s connection to Simcoe aided in his appointment of Lincoln County Sheriff in 1803. Of moderate wealth, William attended school in Ancaster in 1806 studying under Richard Cokrel learning mathematics and land surveying. At the same time studied the classics under the local Presbyterian minister, Reverend John Burns. In 1808 William travelled with his Uncle to Bermuda and Saint Johns. In Saint Johns, he completed his education under the watchful eye of Alexander McLeod.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 100mm 1:2.8 MACRO – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

He returned to the family farm in 1809 and took charge of his father’s farm and also developing a neighbouring parcel of land. William also began his own store, importing and selling goods from Montreal, earning himself a name in the community. As a business owner, he took a Lieutenant’s commission in the Lincoln County Militia and served in a militia cavalry troop. When the Anglo-American War of 1812 opened, Merritt and his cavalry were sent first to Detroit to aid in Brock’s siege of the American post arriving too late to take part in the capture of the city. He would, however, see action at the Battle of Queenston Heights. In the winter of 1813, he dabbled in the timber business when his unit was stood down. After the battle of Stoney Creek, General John Vincent directed Merritt to form a new Provincial Cavalry unit with the rank of Captain. While initially used as runners to carry dispatches, as the British moved to recapture the Niagara region his unit saw participation in several skirmishes. In the summer of 1814, he saw action at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane where he was taken prisoner by the Americans. Like many other British prisoners of war, he spent the remaining balance of the war in an American prison far from the action being released in May 1815. During his return journey to Upper Canada, he met and married Catharine Pendergast. The Pendergasts had fled Upper Canada during the early days of the war and spent the remainder of it in New York. Upon returning to St. Catharines, Merritt returned in earnest to his mercantile business. He soon operated stores in St. Catharines, Queenston, and Niagara (today Niagara-On-The-Lake) as well as one at the Grand River naval station. He sold everything from dry goods, groceries, books, and crockery. But he wanted to expand his business and using his profits purchased a run down sawmill on Twelve Mile Creek. Repairing the mill and building a grist mill, distillery, potashery, and using the salt spring on the property to provide a local salt supply.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:00 @ 20C

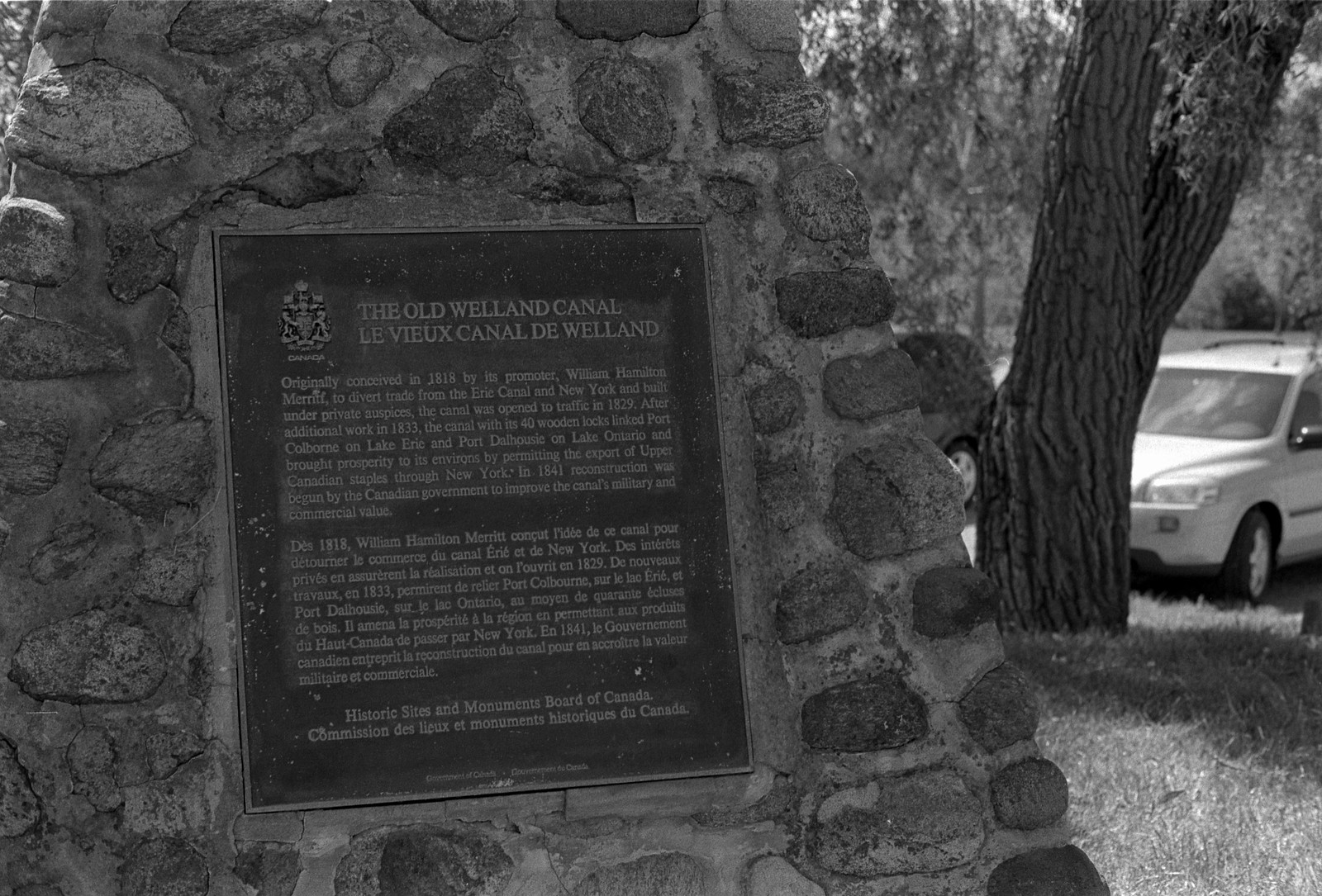

The post-war economic slump hit Merritt hard, much of his business expansion had been done on credit. The first hit was the closure of the Grand River naval station, the loss of that lucrative location would take down his stores in both Queenston and Niagara in order to pay off some of his creditors. To add insult to injury the water level on the creek by his mills never was consistent and in 1818 reached the lowest level they had been since he purchased the property. Without that constant water flow, he could not operate his mills. Merritt began drafting the idea of building a water channel from the Welland River to top up Twelve Mile Creek. He soon gave up the idea as he lacked the money and there remained the biggest barrier on the Peninsula the Niagara Escarpment. But he did not give up the idea and gathered the local business owners and presented a new plan. The idea to build a channel that could not only supply near-endless amounts of water power to local businesses but also open up a safe way to travel across the Peninsula by boat rather than have to complete the portage at Queenston and Chippawa. The idea was well received and Merritt directed to petition the colonial government to help fund the project. Despite having little support from the ruling elite Merritt’s channel presented the merchant barons access to easily move their vast natural resource wealth into American markets, and the fact that Merritt had decided to build his canal with private funds helped the Colonial Parliament to grant a corporate charter. Merritt, however, did not take on the role of President, but rather the financial officer. In that role he travelled across Upper Canada, getting little in the way of funding only promises of support. The merchants in Montreal, were more than happy to throw the needed financial investment Merritt’s way, especially since he had managed to pay off his debts to them. Not having enough, Merritt presented his idea to investors in both England and the United States were more than happy to provide the needed investment. On the 30th of November 1824, Merritt along with other major players in the Welland Canal corporation dug the first shovels of dirt signalling the start of the new canal project.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 50mm 1:1.7 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Merritt played no major direct role in the construction of the canal and mainly handled the financial end of things. And with the successful completion of the project in 1829, his close contact with the Colonial Government had opened up several new doors. In 1832 he ran for and won a seat on the Legislative Assembly for Haliamend County. As an ally of the Tories, he soon found himself and his canal targeted by the growing Reform movement and men like William Lyon MacKenzie named him as a member of the Family Compact, the ruling elite of Upper Canada. In reality, Merritt was never a member of that inner circle and only an ally of the group that helped him get the channel built. Merritt’s only concern was that of his canal and used his post in the Assembly to ensure public support including the loan needed to extend the channel to Port Colborne. And when the infrastructure began to fail, Merritt, now representing his own Lincoln county promoted the idea for the government to buy out the Canal Corporation. Sadly the events of 1836-7 put a damper on the purchase. There is a chance that Merritt stood up with the militia during the Upper Canada Rebellion and may have seen action during the skirmishes that followed but he played no role of note in the actions. He did, however, divest himself of his original mills in 1836 and began to take on roles in other business ventures including the successful Bank of Niagara in 1841. Merritt would also return to the Legislative Assembly of the now United Province of Canada as a representative of Lincoln County but he now allied himself with the Baldwin/LaFontaine reform movement. He even turned down a spot on Henry Draper’s Executive in 1844. Merritt promoted the idea of a Free Trade Agreement with the United States to ensure the stability of the Canadian economy after the repeal of the Corn Laws. Merritt’s role in building and then improving the Welland Canal earned him a position of head of Public Works in 1850 under the new Baldwin/LaFontaine government. In that role, he began a major survey of the province’s waterways and a major canal-building project along the St. Lawerence River to better improve ship and trade traffic into and out of the Great Lakes. He also introduced the idea of improving the mental health services in the province culminating in the construction of the Provincial Lunatic Assylum in Toronto and the use of several old military forts such as Fort Malden in Amherstburg to house the mentally ill. He resigned from the Executive in 1851 but continued to serve on the Assembly as well as various private posts of corporations that had a varied level of success. One of his successes was the completion of the Niagara Suspension bridge, the first bridge over the Niagara Gorge. He stepped down from the Legislative Assembly in 1860, running for and winning a seat on the Legislative Council that same year to represent the Niagara region. A post he would hold for only two years, he died aboard ship while it transited the Cornwall Canal on the St. Lawerence on the 5th of July 1862.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 37-70mm 1:4 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Despite his impact on all of Canada, Merritt is not remembered much outside of the area where he had the most impact, that being the area along the Welland Canal and the communities that grew up because of that canal. As a soldier he successfully allowed veterans of the Anglo-American War of 1812 to apply for the Military General Service Medal in 1862 ensuring that clasps were made for those who fought in the Battles of Detroit, Chrystler’s Farm, and Chateauguay. It was also through Merritt’s efforts that the Second monument to General Sir Isaac Brock saw completion on Queenston Heights after the first was damaged. He also worked to bring many historical documents related to Canada were found and brought to Canada culminating in the creation of the Historical Society of Upper Canada. Plus his effort to bring modern Mental Health treatment to Canada is also remembered today with the continual improvement of those early services which today can be found in the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto the modern name and building for the original Provincial Lunatic Asylum. Only one community along the canal carries his name, Merritton, now a part of St. Catharines which took on the name in 1858 when the original community of Merrittville switched to Welland. He never owned slaves and worked hard to ensure that those who did escape and arrive in Canada were given financial aid, although his first canal did displace an entire black community. As a family man, Merritt and his wife had four sons and a daughter but his work often saw him spend more time away than at home. A strong speaker, but often his ideas were far too complex for the average person to understand. Politically he would easily switch alliances to whoever provided the support for his own gain. His businesses failed as much as they succeeded. Today his remains are buried at Victoria Lawn Cemetery in St. Catharines, Ontario. A plaque to Merritt can be found both at his grave and at the Welland Canal Centre near Lock 3 of the current (4th) Welland Canal.

Written With Files From

J. J. Talman, “MERRITT, WILLIAM HAMILTON (1793-1862),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 16, 2020, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/merritt_william_hamilton_1793_1862_9E.html

Jackson, John N. The Welland Canals and Their Communities: Engineering, Industrial, and Urban Transformation. University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Colossal Project: Building the Welland Ship Canal, 1913-1932. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Great National Object: Building the Nineteenth-Century Welland Canals. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

Styran, Roberta McAfee, and Robert R. Taylor. Mr. Merritt’s Ditch: a Welland Canals Album. Boston Mills Press, 1992.

Jackson, John N., and Fred A. Addis. The Welland Canals: a Comprehensive Guide. Welland Canal Foundation, 1982.

Styran, Roberta M, et al. The Welland Canals: the Growth of Mr. Merritt’s Ditch. Boston Mills Press, 1988.