If you mention the Welland Canal today many people will think of the massive shipping channel cutting across the Niagara Penisula, an artificial river you see from the Garden City Skyway that carries the QEW over the top the channel. Part of an elaborate and technologically advanced highway and major trade corridor from the Atlantic Ocean to the northernmost Great Lakes. The Canal has humble beginnings. Since the earliest days of human settlement in the Niagara Regions, the major transit between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie has been the Niagara River. Even the first peoples realised they required a long portage as the great falls, Niagara Falls, prevented a direct water route. The French and later the English formalised these routes, or Portage Road through 18th Century first between Fort Niagara and Fort Little Niagara (later Fort Schlosser) and then between Queenston and Chippawa. And while many had tried to get a channel built to allow for direct ship traffic, nothing had been done. In 1816 local business owner William Hamilton Merritt had met with some success in the mercantile industry and used his income to purchase a run down sawmill on Twelve Mile Creek in St. Catharines. And while Merritt quickly expanded his operation to include a grist mill and other business ventures, it would soon crumble in a post-war economic slump. To add insult, the water level on the Twelve Mile Creek was not consistent and in 1818 proved too low to operate his mills. Merritt, along with two other local mill owners, George Keefer and John DeCrew, explored the idea of building a water channel to divert water from the Welland River into Twelve Mile Creek. During their survey, the men seriously misjudged the height of the Niagara Escarpment and quickly dropped the idea of a water channel. Instead, they gathered a large number of St. Catharines business owners to float a new idea. Merritt, DeCew, and Keefer presented an idea of a ship channel that would allow for direct travel between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie using Twelve Mile Creek, an incline railway up DeCew Falls, then into the Welland River and out via Chippawa onto the Niagara River. Seventy-Four men signed the petition and directed Merritt to present the idea to the Upper Canada Parliament in York (Toronto, Ontario). While he received a lot of local support, he also got some detractors, namely those businesses in Queenston who relied on the business brought by the Portage Road.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 100mm 1:2.8 MACRO – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

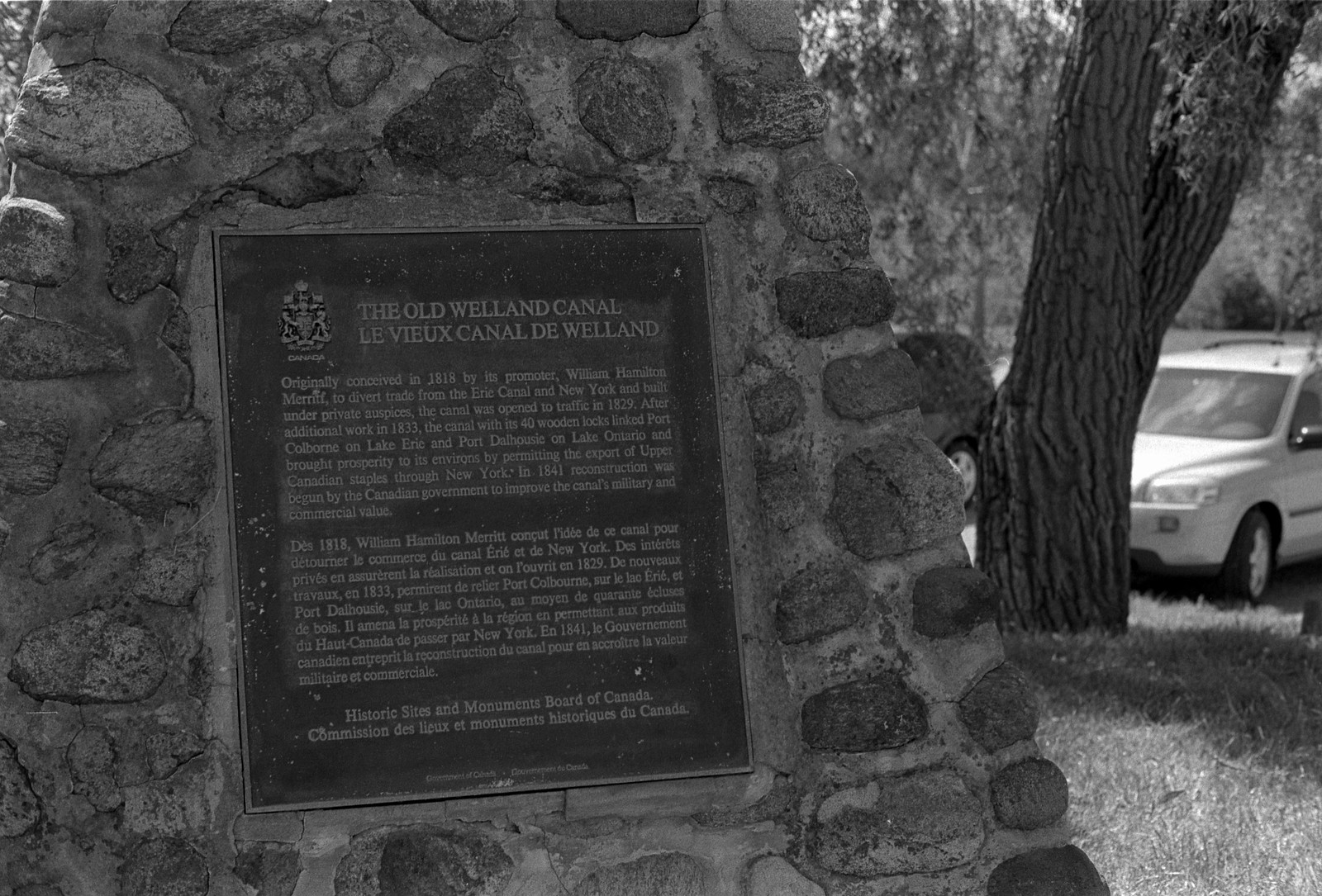

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

In York, Merritt soon realised that his plan for a canal wasn’t the only one being presented to the Colonial Parliament. As part of the post-war defence plan for British North America. The Board of Ordinance recommended the completion of two military canals, one connecting Lake Erie to Lake Ontario at Burlington Bay using the Grand River and a second connecting Lake Ontario to the Ottawa River using the Rideau River. Both canals would allow quick transport of military assets in case of another move by the Americans to invade Upper Canada. The Niagara River and St. Lawrence River is the international border and proximity to American guns. Merritt quickly realised that he might have to seek private money to complete the Canal. Ultimately the Colonial Parliament turned down the military canals, but Merritt had already started to spread around his canal plan with a bonus. His Canal would be for private commercial traffic, not just military traffic. It also granted access to the American Erie Canal which took ships from Buffalo on Lake Erie to New York on the Atlantic seaboard. A Canadian Canal would allow access to his CanalCanal and open up a new market for the growing raw material economy in Upper Canada. A further study saw completion in 1823 by Henry Tibbetts who proposed a new course. The channel would now run along Twelve Mile Creek into Dick’s Creek through the growing downtown on St. Catharines and ascend the Niagara Escarpment through a series of flight locks before a channel took the CanalCanal along the Welland River and into Chippawa Creek. The new route bypassed and reduced the amount of water to DeCew Falls, much to John DeCew’s annoyance. Parliament granted Merritt a charter to form the Welland Canal Corporation on the 19th of January 1824. Merritt served as the Financial Officer and courted the Reciever General of Upper Canada, John Dunn to serve as the Corporation’s president. Dunn accepted the post in 1825 and along with Merritt set out to raise the needed capital. Merritt received support from the Attorney General John Beverley Robinson and the Bishop of York, Reverend John Strachan but only in the form of letters. It gave Merritt an edge, the colonial elites, that being the Family Compact would open up new avenues of support to Merritt. Yet, he only received letters of promise from business owners as he travelled across Upper Canada. It wouldn’t be until he reached Lower Canada that he started to get actual investors from the Montreal merchant barons. He also sought help from outside British North America, attracting investments from both England and the United States.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 50mm 1:1.7 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

By the fall of 1824, the Corporation had the capital needed to start construction. Some two hundred people attended a grand ceremony at the start of the Canal’s only artificial channel for a sod-turning ceremony on the 30th of November, 1824. The ceremony also started the five-year completion clock found in the Corporation’s charter. With construction officially started contracts were tendered and awarded. The actual labour did not begin until July 1825. To save time and money, the locks were to be made from solid oak with most of the locks being built to take the ships up the escarpment, each lock measured 110 feet long, 22 feet wide, and 8 feet deep (33.5 x 7 x 2.5 meters). Around these locks, small work camps grew from tents to huts forming communities like Slabtown, Westport, and Centreville. Work being completed by unskilled labour provided by new immigrants and the black community that lived in St. Catharines. New communities sprung up at the terminuses including Port Dalhousie on Lake Ontario and Port Robinson at the Chippawa River. Above the escarpment, the heavy labour of digging the artificial channel, or the Deep Cut that ran between the village of Beaverdams, Allanburg, Aquaduct and Port Robinson. Work on the project was backbreaking; it also didn’t help that crime and illness ran rampant. Merritt also faced trouble purchasing land from the government as many British army officers saw the investment by Americans as a security risk. Heavy rain through the fall of 1827 ground construction of the deep cut to a halt and forced many labours to move to other work sites. The most significant setback came in 1828, on the 9th of November the deep cut, only two weeks from completion collapsed. Hundreds, if not thousands of workers were killed in the accident. The engineers had misjudged the water level in the Welland River, and it could not provide the level needed to keep the deep cut intact. An additional water source would be required, previous work on the never completed Grand River Canal had resulted in some work being completed on a dam in Dunnsville, and would provide enough water to top up the Welland River and stabilise the Deep Cut. Work began to dig a feeder channel that connected to the Canal at Crowland or Aquaduct as the communities were known. It only took 177 days to dig the channel, no small feat in 1828 and got the project for the Canal back on track. And five years to the day on the 30th of November 1829 the Welland Canal opened with great fanfare. Three schooners, the Annie, the Jane, and the R.H. Boughton transited the Canal with great fanfare arriving in Buffalo only two days after entering the CanalCanal at Port Dalhousie.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 100mm 1:2.8 MACRO – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Travelling the Canal was no small feat, even after the Canal completed the communities that grew up around the Canal provided homes for the people who operated the Canal. Lock tenders, hotels, taverns, even teams of oxen and horses dragged the ships on towpaths through the Canal. And true to his word, the Canal also offered the sale of water power which began to see the construction of mills in these growing communities. Only a year into the service of the new CanalCanal a problem came back to haunt them. The terminus at Chippawa proved problematic, the proximity to Niagara Falls meant that one wrong move would sweep the ship over the edge and ultimate destruction. The canal corporation began to consider realigning the exit directly into Lake Erie. After securing a loan from the Colonial government, they selected Gravely Bay in 1831 as the new terminus. While a lock would remain at Port Robison to allow traffic in and out of the Canal into Chippawa Creek, a new channel would be cut to connect to the deep natural harbour at Gravely Bay. Almost as soon as construction started, they began to see major delays. Heavy rain, malaria and even a cholera outbreak through 1832 threatened the whole project. But the Corporation plunged onward completing the new channel in 1833 and renamed Gravely Bay to Port Colborne. A single schooner, the Matilda travelled the whole Canal without fanfare before continuing onto Cleveland, Ohio to open the extension. The extension was only a stop-gap and ultimately the death blow for the Canal and the Welland Canal Corporation. Merritt had gone on to bigger things and now sat on the Provincial Legislative Assembly. The Corporation now burdened with debt and not taking in income needed to repair the wooden locks now falling into disrepair. And by 1836 the whole system had ground to a halt, and the Corporation and Merritt began to make overtures to the government to have them buy out the entire Canal. The trouble was that the government was spiralling towards civil war and already the radical elements of the reform movement had investigated the Canal corporation for its ties to the Family Compact. Merritt himself had been named as a member of that elite circle (incorrectly). And so the Canal would have to wait.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 50mm 1:1.7 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Today there is little left surviving of the First Welland Canal. Most of the wooden locks were dismantled and built over during the construction of the Second Canal or were too far gone to be salvaged. However, there does remain some evidence of the first Canal that do survive today. Two locks remain relatively intact and visible, the first in St. Catharines’ Centennial Gardens that was discovered during the construction of the park in 1967 complete with the wooden lock walls and are preserved under concert but are visible. A historical plaque is also nearby marking the location of Lock 6. Further along in Mountain Locks Park in Merritton are the remains of Lock 24 but are currently overgrown by grass there is also a plaque marking the location. While buried, Lock 1 remained intact at Port Dalhousie but cannot be seen above ground and I’m unsure if there is a plaque marking the location. During this time of plague, access to the beach is limited to residents of the Niagara region only. A small section of a trench from the first Canal is also present near Welland Vale Island although no markers are present. The most important reminder of the first Canal is the following three canals and the communities that grew along the canal path. Communities like Port Dalhousie and Merritton (formed from Centreville, Westport, and Slabtown) have been since 1960 a part of St. Catharines. Aquaduct became Merrittville, and then Welland remains a separate city as does Thorold, which absorbed both Port Robinson and Allanburg. But the Canal itself would not be forgotten and proved the continued need for a faster route across the peninsula.

Written With Files From

Jackson, John N. The Welland Canals and Their Communities: Engineering, Industrial, and Urban Transformation. University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Colossal Project: Building the Welland Ship Canal, 1913-1932. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Great National Object: Building the Nineteenth-Century Welland Canals. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

Styran, Roberta McAfee, and Robert R. Taylor. Mr. Merritt’s Ditch: a Welland Canals Album. Boston Mills Press, 1992.

Jackson, John N., and Fred A. Addis. The Welland Canals: a Comprehensive Guide. Welland Canal Foundation, 1982.

Styran, Roberta M, et al. The Welland Canals: the Growth of Mr. Merritt’s Ditch. Boston Mills Press, 1988.

1 Comment