By 1836 the Welland in its current form remained woefully behind the times. Compared to the canal systems along the St. Lawrence River, the military Rideau Canal, and the under-construction Trent-Severn waterway, the Welland Canal remained little more than a cheap imitation to the technology of the day. Technology had moved on, and most ships now used steam power rather than sail power larger ships, especially those with side wheels and greater drafts and displacements prevented the larger modern cargo and passenger vessels from fitting through the canal. To simplify the problem, the Welland Canal had outgrown its usefulness. But the need for a canal had not gone away; the canal had not only provided a new trade corridor it also granted urban and industrial growth across the region. The wooden locks were, by the late 1830s started to fall apart preventing transiting the canals, the small income that was coming in from the sale of water rights could not help pay off the debts racked up by the Corporation. And as a result, the Corporation had no money left to repair, the Corporation was caught in a vicious cycle. Without a fresh infusion of capital, everything could and would fall apart. The Corporation turned to the only allies they had, the Upper Canada Parliament. Not only had the Family Compact provided support in the early days, but William Hamilton Merritt also sat on the Legislative Assembly and had ties to the Compact. On the flip side, the ongoing troubles in the government with the radical reform under William Lyon MacKenzie investigated the ties of private corporations to the government. Of course, when everything went south during the Rebellions and Conflicts of 1837-8 did not help matters along. Lower Canada was forced, and Upper Canada voted in favour of the union and under the Act of Union 1840 Upper and Lower Canada became a single Province of the Empire, the Province of Canada in 1841. The Surplus and Debt of the two former Provinces cancelled each other out, and in the act of Parliament in 1841 the government bought out the canal and took over its operation.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Government engineers not only saw a chance to repair the canal but improve it overall. New locks with stone walls and iron infrastructure they also saw an opportunity to improve the route of the canal to allow for the larger ships to bypass the less than ideal sections of the canal. The new locks measured 46m long, 8m wide and 3m deep to accommodate these larger vessels both private and military craft on the great lakes. Some areas of the old channel could be reused, but in other areas, a new channel needed to be created or run in parallel with the old channel. One of the most significant changes took place in Port Dalhousie; the natural harbour was dredged to accommodate the larger vessels and move the canal’s entrance further inland to make better use of the harbour. The same was done at Port Colborne. Another project as part of the new canal was to enlarge the feeder canal not only to improve the water supply but to allow ships to navigate the feeder channel and access a secondary entrance at Port Maitland onto Lake Erie. There were fears (groundless eventually) that it might divert traffic away from Port Colborne. The lock at Port Robinson would see an update to allow transit onto the Chippawa River and an Aquaduct as well to gain access to the Welland River. The new canal, known to locals as either the Government Canal or the Stone Channel would provide not only improved navigation along the canal but also encourage transit along natural waterways and improve the water flow for industrial growth. A new channel would be completed at the Mountain Locks about ninety meters south of the first channel, to allow for ships and workers to use the old channel to ferry materials and labour to the new work sites. Construction began in 1842 and workers flowed in not only from Canada but from the old world as well. Stonemasons from Scotland formed massive limestone blocks from the quarries in Stumptown, Irish fleeing increased violence on their home island arrived to provide the unskilled labour to dig out new channels, harbours and locks. Working conditions proved poor, violence and crime a common sight. Despite being a government project, private firms gained the needed contrasts to complete the actual work. Working conditions were harsh and workers, especially the unskilled labourers mistreated. To make their demands heard they rioted and early in the project marched on the largest urban centre, St. Catharines. When their words weren’t heard, they turned to violence and looting local businesses and supply warehouses of the Corporation to ensure their very survival. The protests were put down, and some conditions improved but not by much. To keep the peace, a small provincial unit of men of colour, both former slaves and free men were raised to act as a police unit, officially a militia unit. The white workers took offence, while slavery had been abolished in the Empire since 1833, racism ran deep. It wasn’t the colour of the men that the Irish took offence to, instead of the red coats that were a symbol of English oppression, the oppression they attempted to flee from by coming to Canada. Even among the worker’s tensions were high and Roman Catholics and Protestants of Irish decent often fought amongst themselves. Despite everything, the project came to completion with little fanfare in 1845. The old sections were quickly abandoned and their locks demolished or buried in some cases. The Stone Canal now operated twenty-seven locks, of which twenty-five made up the mountain locks.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

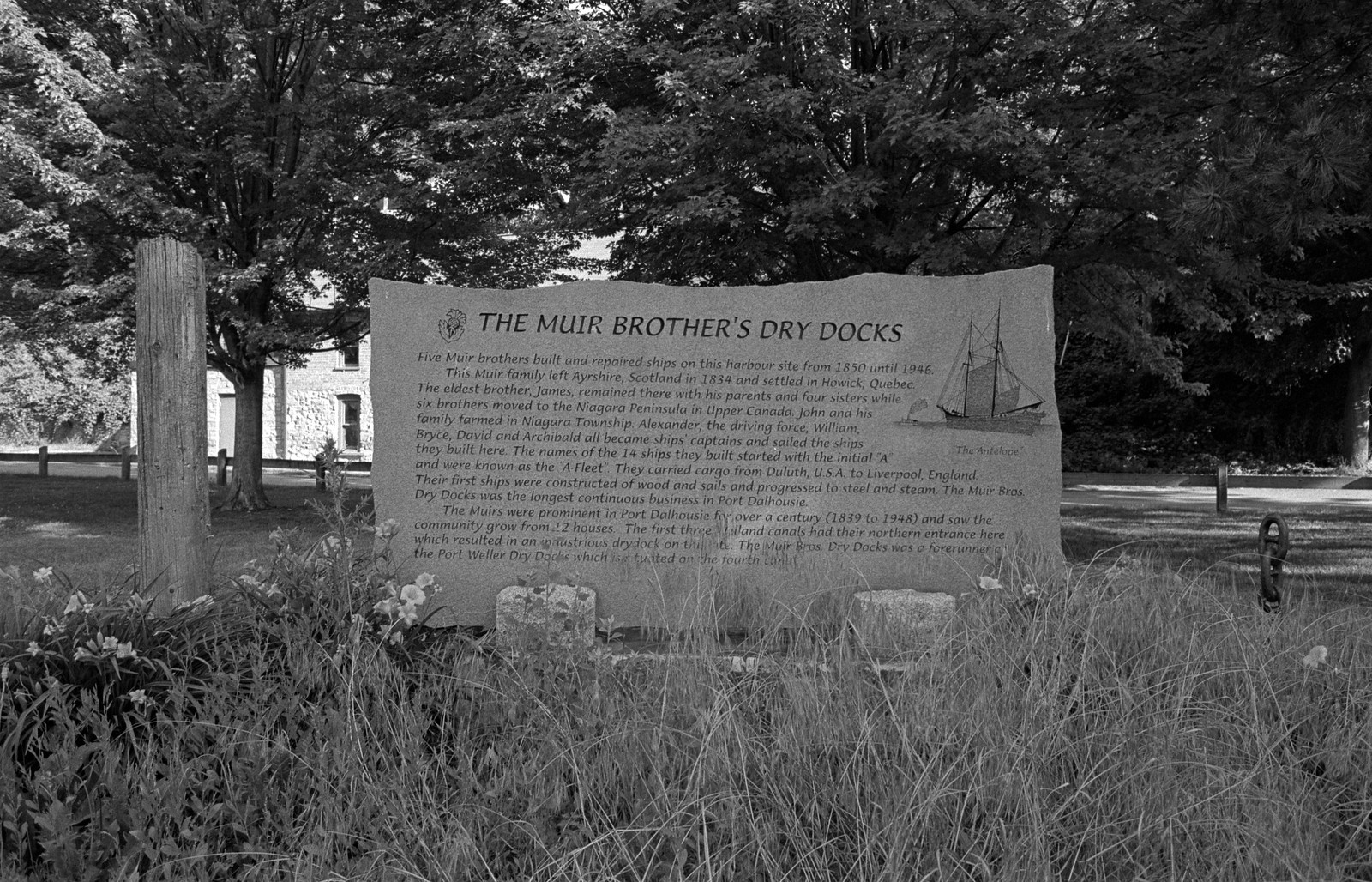

While the first canal had formed the foundation, the second canal allowed for rapid urbanization and industrialization of the regions along the route of the canal, shantytowns became permanent settlements, places like Stumptown became Thorold, and the four settlements below the escarpment joined together to become Welland City. Aquaduct became Welland, and Port Beverly changed to Port Robinson. The presence of the Mountain Locks with their advanced and extensive water supply system created an ideal spot for major industrial growth. Shipyards sprung up at all the major port communities, among the most famous the Muir Brothers at Port Dalhousie. Industrial growth exposed at St. Catharines along with Thorold and Merritton. At Thorold, one of the first cotton mills in Canada West marked a transition from simple raw material preparation to proper manufacturing of goods. The canal also acted as a transportation hub that allowed for improved regional transportation—allowing for raw materials to flow between businesses and manufactured goods to go onto larger projects, including ship construction. In 1852 the first railroads began to cross the Province while many saw railroads as a threat, Merritt saw an opportunity. Great Western Railroad would be the first to cross the Canal at Welland City. A year later the Welland Railway began to build a railway that ran along the length of the canal. The railway would allow for year-round movement of cargo and passengers along the canal route and provide faster movement and greater reach and access to the canal. The Welland Railway would see completion in 1859. The new canal also brought about the improvement of local roads and the increased number of swing bridges over the canal to allow for further movement of goods in the whole area around the canal. The 1850s saw improved depth to the canal to match those of the locks being built (under the direction of Merritt) along the major rivers through Canada such as the St. Lawrence, St. Claire, and Detroit Rivers. Merrittville would be named the seat of Welland County in 1858 and take the name Welland. Welland City, to avoid any confusion took the name Merritton, although locals continued to call it Factory City due to a large number of industrial sites in the grown community. But the new decade brought new troubles for the canal.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

By 1861 it became obvious that the canal needed more water, between the increased depth and demands on the locks along with the increased amount of industry making use of the water power generated by the canal. But the Provincial Government had bigger problems. The canal itself presented an excellent target with the increased tensions with the United States, even more so during the American Civil War saw the Canadian government create a militia unit, the Welland Battery to defend the canal. The battery, although their guns were kept in Hamilton and they often drilled as infantry rather than artillery with surplus rifles, would provide the local defence of the Port Robinson and Port Colborne access to the canal. Even the Fenians would make the canal a target during their raids into Canada in 1866 to allow their forces access across the peninsula. The confederation of four British North American provinces in 1867 into the Dominion on Canada transferred ownership of the canal to the new Federal Government. Plans began to take shape for a new canal to be completed. Construction of the third canal began in 1872. But already the need to maintain the second canal came to light. The power provided by the second canal needed to be maintained. When the third canal saw completion in 1881, and the new canal also answered the water supply need to the second canal. While ship traffic would be limited across the second canal navigation between St. Catharines and Thorold were cut off, the water power would be maintained even in the closed sections. The Welland Railway was absorbed into Grand Trunk along with Great Western by the middle of the 1880s. The late 1880s also brought about a change in how factories were powered with the introduction of electricity, with the first small plants in the canal region opening in 1887 at Merriton on Lock 12 followed by generators specifically to drive factory machines. The same year and electric interurban railway opened to move both people and goods between the major canal communities between Port Dalhousie and Welland. The last factory to open along the second canal came in 1888 with Canada Hair Cloth opening at St. Catharines. The twentieth-century and construction starting on a forth canal starting but the final countdown on the second and third canal. Even then the last ships transited the second canal in 1915. When the forth canal opened in 1935, all navigation and water flow into the third and second canals were shut off.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Even before the canal was shut down, most industries had departed from the former communities. Only the largest production factories survived the great depression. The second canal became a focal point of former glory and also an open sewer. Pollution had been dumped freely into both natural and artificial waterways for nearly a century now and the whole second canal became an industrial scar across the landscape. The first efforts to clean up the canal came in the 1950s with entire sections of the canal buried and treatment plants installed. The merger of several smaller communities into the major ones like St. Catharines, Welland, and Thorold allowed for more clean up through the mid-century. The second canal became a point of pride, lock doors were removed, and water flow increased and pollution cleaned up. The old mountain locks were turned into a park as was canal valley. Old industrial sites in the former town on Merritton were renewed in the early 21st century and now form a core commercial centre in the previous town. Even Thorold restored its downtown and the old Welland Mill. Of all three historic canals, the second canal not only saw operation for almost a century it is also the one that you can see and follow the easiest. In St. Catharines you can still see locks 1 through 3, 5 through 13, 15 through 21. In Thorold, only lock 25 is visible. The Port Robison, Welland, and Port Maitland locks are still visible as in Lock 27 in Port Colborne. Canada Hair Cloth was transformed into the Marylin I Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts part of Brock University in St. Catharines. Beaver Cotton Mill is a Keg Franchise, Lybster Mills is an Italian Restaurant, and the Riordan Paper Mill is an automotive Shop. The Welland Mill in Thorold is a mixed-use Commercial and Residential building. If you’re looking for an easy way to explore the historical Welland Canals, then I highly recommend looking at the Second Canal, as you can see there is a lot leftover and well worth a walk and exploration.

Written With Files From

Jackson, John N. The Welland Canals and Their Communities: Engineering, Industrial, and Urban Transformation. University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Colossal Project: Building the Welland Ship Canal, 1913-1932. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Great National Object: Building the Nineteenth-Century Welland Canals. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

Styran, Roberta McAfee, and Robert R. Taylor. Mr. Merritt’s Ditch: a Welland Canals Album. Boston Mills Press, 1992.

Jackson, John N., and Fred A. Addis. The Welland Canals: a Comprehensive Guide. Welland Canal Foundation, 1982.

Styran, Roberta M, et al. The Welland Canals: the Growth of Mr. Merritt’s Ditch. Boston Mills Press, 1988.