When it comes to all the posts I’ve written about the Welland Canals, this one is probably the most important. The reason is that if it hadn’t been for the efforts to save the historic Welland Canals, this whole project would not have been worth creating. The reason is that there would be nothing left of the first Canals at least in original forms. Sure there might have been plaques installed eventually, and some sections of the earlier Canals may have survived, but I don’t think in any meaningful sense. The preservation of the historical Welland Canals was the last thing on the minds of those who worked to build the newer canals, and it wouldn’t be until the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Canal that the earliest efforts were undertaken. When the Second Canal was built, it wiped out much of the First Canal. As the Third Canal rounded out completion, the Second Canal saw continued service as a source of water power. And by the time the Fourth Canal was operating, the rapid urban expansion and cleanup efforts were needed to improve the health and well being and allow for the rise in population, so whole sections were lost. But at that same time, you saw the major efforts to preserve the Historical Sections start. In fact, through the 1920s and 1930s is when you saw the first efforts to preserve Canada’s historical buildings. Several older forts in the area, Fort Erie and Fort George were rebuilt as National Historic Sites, plaques were raised across the country at every major event site or birthplace. Although the salvaging of the original Canal infrastructure became a local effort. And it’s those efforts that allowed this project to be far more photographically interesting.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 100mm 1:2.8 MACRO – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 50mm 1:1.7 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

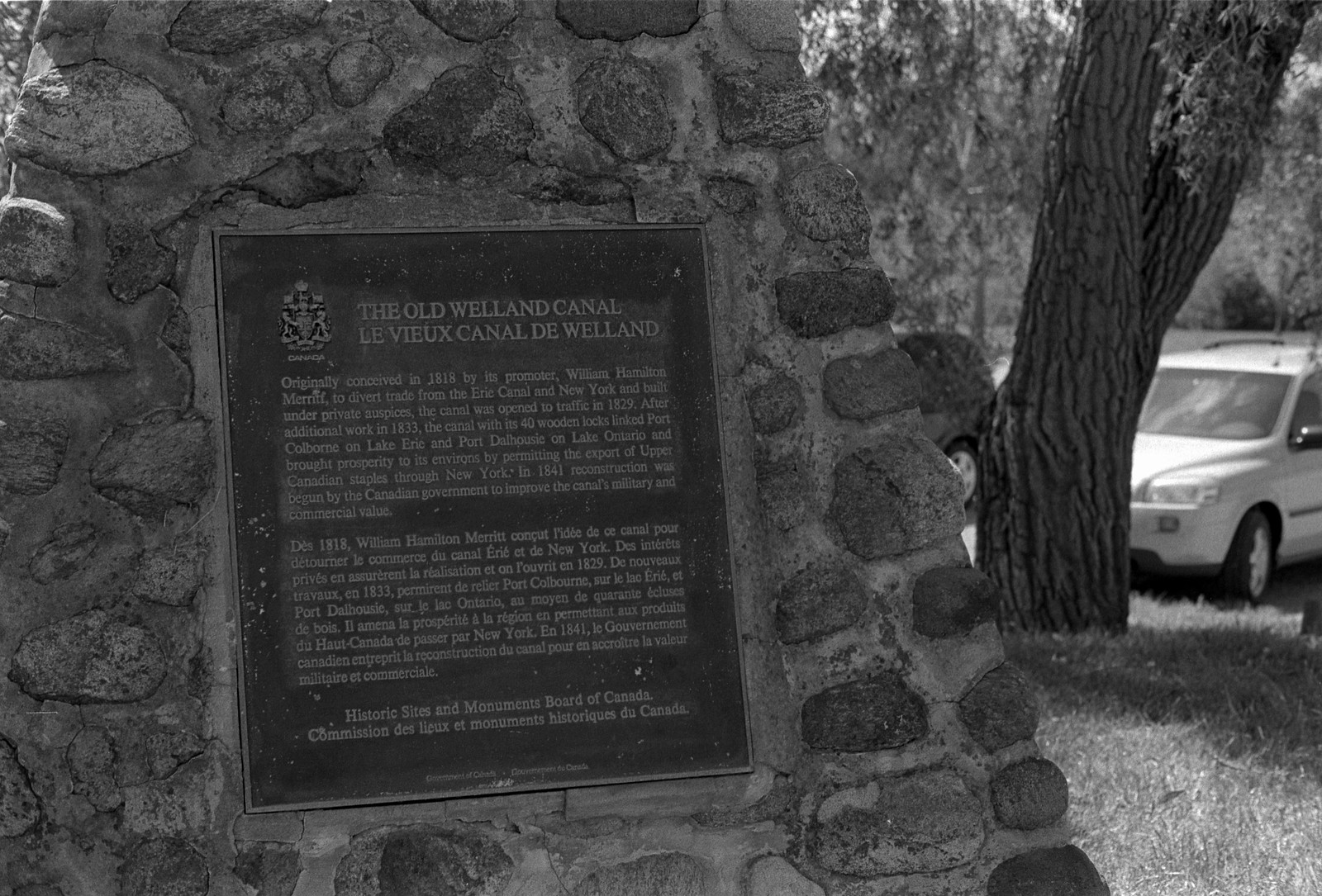

When the Second Welland Canal first opened in the 1840s, it became not only the focal point for ship traffic but also regional transport and most important industry. While early industries in the region focused on processing, grist mills ground wheat and other grains into flour and sawmills took timber and turned it into lumber; industrial pollution was being produced. While not in the same climate-changing volumes as today, but plenty of water pollution saw ejection. Sawmills proved the worst offenders and also required far more water flow on even the smallest of operation. But as the decades rolled past, the heavier industry began to arrive. More and more pollution saw ejection into the waterways and the air as rubber plants, carbide factories, not to mention pulp and paper mills. While the Third Canal removed most of the ship traffic from the Second Canal, the use of the old Canal not only as a source of power for a hydroelectric generation it also made an excellent spot to dump garbage and pollution. The main industrial towns, Merritton, Thorold, St. Catharines, and Welland, were the hot spots. It also didn’t help that many locals got their drinking water from the old Canal. And the industry only got bigger, steel, ore refining, heavier manufacturing, greater levels of pollutants being dumped into the old Canals did not help much. When the Fourth Canal began construction, and larger hydroelectric generators built to supply the increasing needs, water flow to the Second Canal was the first to be shut off. This only made the matter worse as the stagnate water continued to collect industrial pollution and was an open sewer. The late 1920s proved to be a rough decade. Much of the early industrial powerhouses of Thorold and Merritton began to see a majority of their factories shut down. However, the decade did bring one thing, the installation of the first plaque on the Welland Canal in 1924 as the Federal Government moved to mark vital historical sites. The plaque, located at Allanburg along Highway 20 near Bridge 11 marked the site where official opening of the construction of the First Canal took place in 1824. One of the first cleanup efforts to take place along the former Canal happened in Port Dalhousie. The Muir Brother’s drydock had ceased ship construction in 1891, and a decade earlier the Royal Canadian Henly Regatta began to operate on the Inner Harbour, better known as Martindale Pond. By 1903 a grandstand had been built to allow for larger numbers to watch the event. With the Fourth Canal now in full operation by 1932 the Inner Harbour was no longer a major port of entry into the Canal system. Efforts were undertaken to have the pond cleaned up and dredged to a proper depth. The efforts in Port Dalhousie did not go unnoticed; local governments began to hear grumblings by their residents of the communities along the old Canal who no longer appreciated living near an open sewer. Different communities took different approaches. In Thorold, the whole section of the Second Canal that ran through the downtown was buried, a small area became the Battle of Beaverdams Park with only a small part of the lock visible above the surface, while most of the park dedicated to housing the monuments to the battle of the same name from the Anglo-American War of 1812. The complaints were enough that the first step to aid in the cleanup was the reintroduction of water flow through the old channels. The next was a widespread investigation into the local water supply, and a 1940s report indicated that a sewage treatment plant must be built. The entrance of Canada into the Second World War put that idea on ice.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 50mm 1:1.7 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 50mm 1:1.7 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

The first treatment plant opened in 1950, and through the next couple of decades, massive cleanup efforts were undertaken. The old channels of the Second Canal had their lock gates removed to allow for constant water flow at a lower level to prevent any stagnation. The water was run through treatments, and local water supplies moved to cleaner sources. The Canal beds were dredged free from nearly 200 years of waste. The City of St. Catharines would begin the process of turning whole sections of the Canal Valley and the Mountain Locks into parks with walking trails. The Canal Valley became the Centennial Gardens in 1967, during the construction several mills and factory ruins were cleaned up, stabilised and turned into features. Also during the process, the remains of Lock Six from the First Canal were discovered and left in place with a concrete pad atop the surviving lock walls. Similarly in Merritton (now a part of St. Catharines) the Second Canal Mountain Locks were cleaned up and turned into Mountain Lock Parks. Much of these efforts were made in coordination with the Welland Canal Parks Committee headed up by George Seibel. The Committee would work to coordinate local groups and Government in an attempt to transform the whole old Canal into a national historic area. The cornerstone of his efforts was focused on the Third Canal Mountain Locks. By this point, entire sections of the Third Canal were lost to urban expansion through St. Catharines, with only a couple of locks and features surviving, the first, second, and fourth locks were still visible, but the late 1960s had filled in the primary trench. The plan for the Mountain Locks was the creation of a National Historic Site that encompassed the Eleventh through Seventeenth Locks. In addition to showing off a working set of locks, it would also include the first railroad tunnel that ran under the Third Canal (we know it today as the Blue Ghost Tunnel) and a museum highlighting the history of the Canal. Unfortunately, the expansion of the General Motors Plant and lack of Government interesting and funding suck the plan. Port Colborne also undertook efforts to preserve the old Canals, stabilising the old exit locks from the Second and Third Canals, which also provided water for Lock 8. And in 1979 launched a local festival celebrating the Canal region known as Canal Days. Through the 1970s and 1990s, the Welland Canal Society undertook an effort to ensure plaques were installed throughout the Welland Canal and arranged for the excavation to uncover Lock 24 from the First Canal making it a part of Mountain Lock Park. They also installed plaques highlighting other key areas to the Welland Canal. Sadly this group collapsed in 1991 as funding dried up.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

The Canal corridor as a whole suffered through the 1990s as a recession began to crack the local industries. Cities like St. Catharines, Welland, Thorold and Port Colborne all suffered under the weight of decline and urban decay. Yet as the new century approached things did turn around, and a great deal of urban renewal took place through the older communities of the Canal. St. Catharines began a series of cleanup efforts in Port Dalhousie, knocking down old buildings, restoring parks and other structures that could be reused. And they were turning Lock 1 of the Second Canal into an outdoor music venue. Merritton’s old factories were restored and reused as commercial buildings. One of the immense efforts took place at the Lybster Cotton Mill. The original 1866 cotton mill had been long lost behind a century of industrial growth as Domtar had purchased the property and operated a large paper and pulp factory. Nearly all the additions were demolished and the original building restored. The effort formed a new commercial core in St. Catharines and brought much needed urban renewal to the former community. St. Catharines also went through their downtown, demolishing an old arena and replacing it with a brand new mixed-use centre and converting the Canada Hair Cloth Factory into a satellite campus of Brock University. Thorold did the same, restoring the 1846 Welland Mill that had been shuttered since 1929, turning it a mixed commercial/residential building. Even the old fire hall got a needed restoration and conversion into a commercial property. Smaller communities like Port Robinson saw several buildings get much-needed attention including the restoration of their 1863 brick schoolhouse and the Upper House in Allanburg. And while some communities are seeing a rebirth, others still need efforts. Welland is making improvements, but there remains a widespread urban decay through the downtown and outer sections of the city. And while Merritton’s commercial core is hopping thanks to the presence of freshly restored buildings the historic downtown is still in need of some cleanup. Similarly, Welland, which took a significant blow in the early 2000s with a tonne of industry closing is slowly making some efforts towards cleanup, but still has a great deal of urban decline and decay throughout. The effect on the whole region has been positive with tourist traffic once again coming to the area. Today, the efforts of local groups continue to shine a light onto the history of the Welland Canal, folks like the group on Facebook, Friends of the Welland Canals and the Welland Canal Advocate.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

As I mentioned at the beginning, it is these efforts that have done this project what it is today. I love visiting the region, full of rich history, impressive buildings. One of the best ways to discover the Canal is by attending a hike hosted by the Welland Canal Advocate. Sadly I have only heard one such walk, but as you can see, it had a significant impact. Another option is to explore the canals yourself. I’ll be getting into that in next week’s final post in this project. Some of the best spots to explore the Canal and its history is in St. Catharines with Centennial Gardens Park and the historic downtown. Port Dalhousie also have a lovely restored downtown and a great local craft brewery, Lock Street Brewery. Similarly, Port Colborne is an excellent spot to take in the Canal and enjoy a good restaurant. Either way, there is lots to offer and explore.

Written With Files From

Jackson, John N. The Welland Canals and Their Communities: Engineering, Industrial, and Urban Transformation. University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Colossal Project: Building the Welland Ship Canal, 1913-1932. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Great National Object: Building the Nineteenth-Century Welland Canals. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

Styran, Roberta McAfee, and Robert R. Taylor. Mr. Merritt’s Ditch: a Welland Canals Album. Boston Mills Press, 1992.

Jackson, John N., and Fred A. Addis. The Welland Canals: a Comprehensive Guide. Welland Canal Foundation, 1982.

Styran, Roberta M, et al. The Welland Canals: the Growth of Mr. Merritt’s Ditch. Boston Mills Press, 1988.