History is far more complicated. And when it comes to the history of the railroad in Ontario, there are many more moving parts to the story than most people think. The history of the railroad does not begin in the 19th Century; rather, the events of the early 19th Century are simply a culmination of a vast array of the human need to improve our own mobility beyond that of our own two feet or the control and domestication of animals. As I am fond of saying, there has to be context to understand. While this is not the furthest I’ve gone back in time, but certainly the furthest back in human history. The idea of a tracked roadway, a means of guiding human drawn carts, goes back far into the dark and ancient past. The earliest of these trackways can be found in England, dating to 3838 BCE. The Post Track in England’s River Brue Valley is a surviving set of heavy ash planks pegged every three meters (by modern measurements), making it easy for a wheeled cart to travel a distance when wayfinding was rudimentary. While many other such trackways have been discovered across England and Mainland Europe, the Post Track remains the oldest discovered. While the purpose of these early causeways remains lost in time, the Greeks improved upon this early innovation. Ancient Greek and even Roman Roads have been discovered to have grooves that fit perfectly on carts or chariots to guide them along set paths, again allowing the animals and humans guiding them to follow a set path without much thought. While these earliest forms of a set route relied on either grooves or raised wooden planks, the earliest known example of a railroad would not show up in the history books until 1515 CE; a wooden incline railroad would allow visitors to the Austrian Fortress of Hohensalzburg. The Reisszug consisted of a car that could be hauled up and down an incline using human or animal power when connected with a hemp rope.

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28-135mm 1:4-4.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

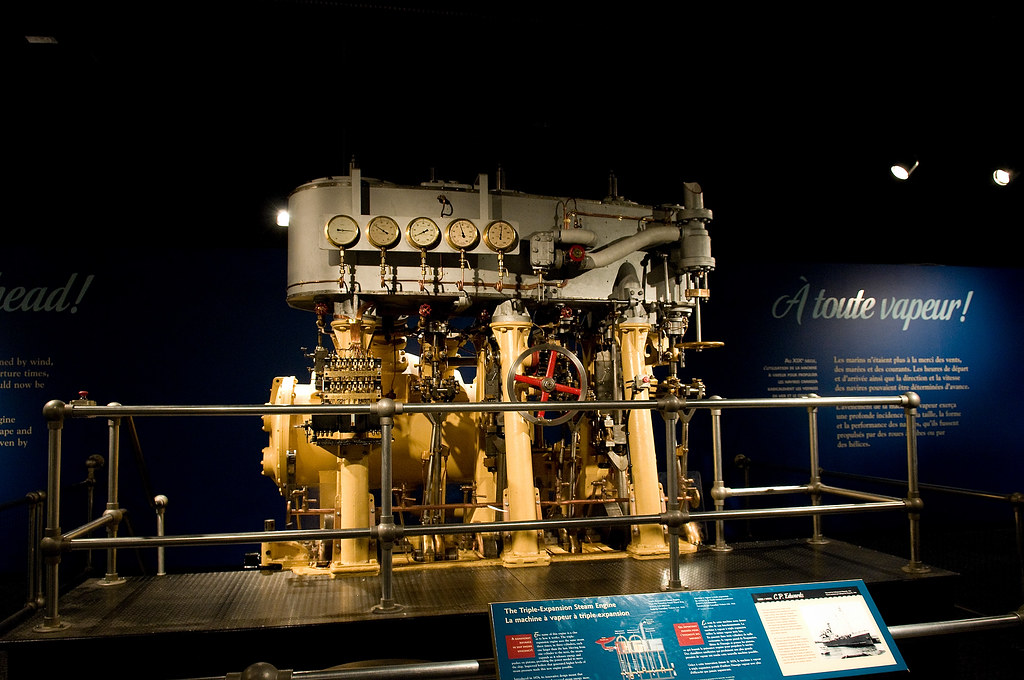

With tracked systems taken care of, the next bit of technology needed is the motive power, the earliest being steam power. Throughout the course of ancient history, the exploration of steam and steam power say exploration throughout the ancient world, through the Greeks, Egyptians, Chinese, Persia and even ancient France. But these were simple curiosity with no real practical purpose. The earliest practical use of a steam engine would power a simple water pump, credited to Thomas Savery in 1698. The Savery engine, while useful for small applications, tended to fail explosively when the size and power output increased. Thomas Newcomen, in 1712, improved upon the Savery design allowing power to be transferred constantly through the use of a piston device but failed to solve the large scale problem. That would not happen until Jacob Leupold invented a two-cylinder high-pressure steam engine in 1720. Further improvements saw creating a flywheel and crankshaft to allow the power to be transmitted and moved to power machines. Although like many inventions, James Watt saw the parts and combined them into a single device. The Watt Engine took all the previous innovations, and in 1769, he revealed the first scalable and practical steam engine kicking off what we know today as the industrial revolution. The Watt design would change how work was done; water power would be slowly replaced by steam power allowing massive factories to open up manufacturing. One thing that also saw improvement was metallurgy allowing for more efficient creation of cast iron which proved far better materials for tracks on incline railways. Steam power replaced that of humans to haul cars up and down steep inclines. While heralded as a success, the Watt engine had one problem, it was stationary. William Murdoch, in 1784 managed to take a Watt engine and create a self-propelled steam motive power carriage. At least a small working model. And by the end of the century, an l-shaped rail and flanged wheel allowed for improved traction of a track driven carriage.

Sony a6000 + Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 17-55mm 1:2.8G DX

While both tracked vehicle and steam locomotion saw development on near parallel if not complimentary tracks, the stage would be set for combining the two. The earliest documented steam locomotive came in 1802, credited to Richard Trevithick. While he is known as the first, the Trevithick Locomotive saw little use outside of curiosity. The first commercially successful locomotive came in 1812, named Salamanca, designed and built by Matthew Murray, followed up quickly a year later by the Puffing Boy, the result of inventors William Headly and Christopher Blackett. George Stephenson’s Blucher a year later took the world by storm as Stephenson took the previous locomotives and combined the best elements. Produced in 1814, the Blucher (a 0-4-0 under Whyte Notation) added in an improved flanged wheel design for improved traction on cast-iron rails. These early engines saw their primary use in the mining industry and were often heavy and underpowered for their assigned task. The second problem would be the cast-iron rails which proved brittle and broke easily under the heavy locomotives. Improvements by William Lash in 1820 improved the strength and methods for casting the iron helped along by steam engines in the production process. These early railways carried only good and often required both animal and steam power. The first truly steam motive railway came in 1822, the Hutton Railway, but again it simply made the movement of mined material easier and faster. The idea of using a railroad to move people quickly would start at the end of the decade. The goal was to construct a line between London and Manchester. Several inventors put forward a design for the locomotive to drive the railway. Rocket (A 0-2-2 Whyte notation locomotive) was designed and built by Robert Stephenson, son of George Stephenson (Chief Engineer of the London & Manchester project). Entering the Rocket in the 1829 trails, it won with flying colours. The London & Manchester Railroad opened to passenger service in 1830, and within six years, some 2,000 kilometres of tracks crossed England.

Nikon D70s – AF-S Nikkor 18-70mm 1:3.5-4.6G DX

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

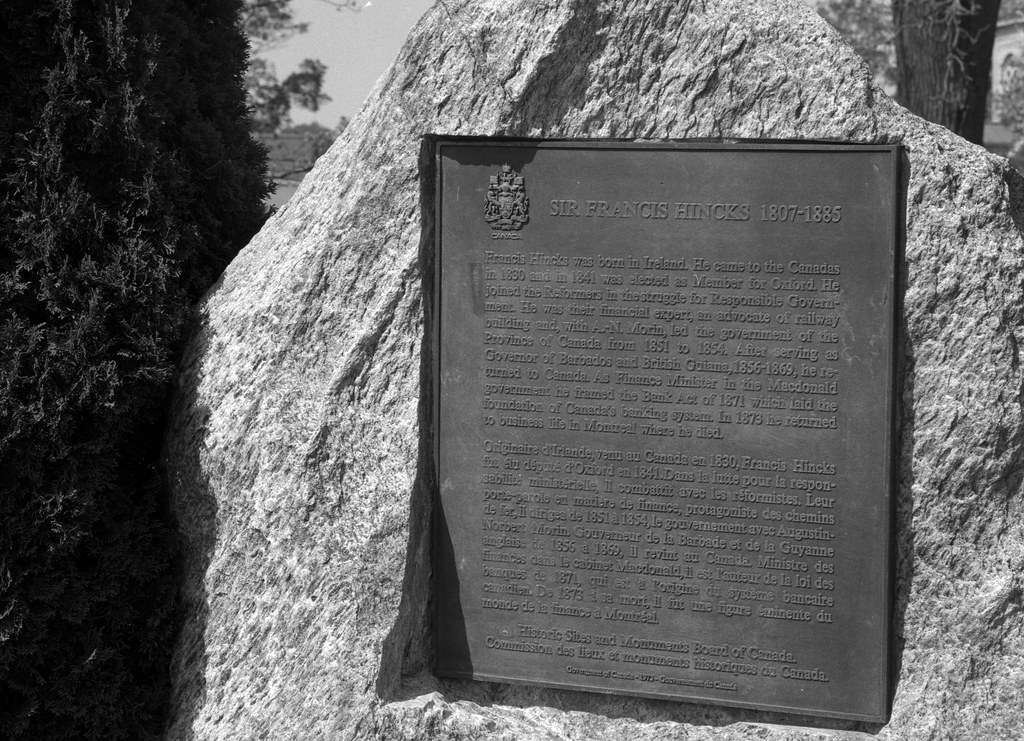

Railroad mania would not stay in England for long. While incline railroads and steam power had started to arrive in British North America through the 1820s and 1830s, some saw use in constructing improvements to the Quebec Cititdals. One of the wildest ideas for an incline railroad came with the idea to use one to lift ships up and down DeCew Falls as part of the first designs of the Welland Canal. The first steam-powered railway started construction in 1832. The Champlain & St. Lawerence Railway would act as a Portage line to bypass and provide year-round transport around a tough section of the St. Lawerence River from La Prarie and St. Jean in Lower Canada (the modern province of Quebec). Sponsored and financed by brewing giant John Molson the railroad could provide a near-constant means to move goods. Operations started in 1836, marking the first true steam railway in North America. The merchants in Upper Canada (the modern province of Ontario) caught on to the idea, Sir Allan Napier MacNab. MacNab, Peter Buchannan and Isaac Buchannan, with the help of Samuel Zimmerman, chartered the London & Gore Railway that same year. And Frank Capreol, not to be outdone, chartered the City of Toronto & Lake Huron Railway. Of course, the political reality ensured that neither of those lines went beyond the planning stage. The entire province was thrown into political and civil turmoil as the Rebellions in Lower and Upper Canada, followed by the Patriot Wars, resulted in much instability in the area. It didn’t help that the union of the two Canadas into a United Province of Canada resulted in further instability.

Yashica-12 – Yashinon 80mm 1:3.5 – Fuji Provia 100F @ ASA-100

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

While the 1840s resulted in many improvements and colonial expansion throughout the region, the construction of railways would not start until the arrival of responsible government and some level of self-determination arrived by the end of the decade. One thing that did see a great deal of growth was the domestic manufacturing industry. An example being the James Good Foundry in Toronto, Good an Irish imminent, began his business constructing small household goods and stationary steam engines. Eventually, the name of his foundry became the Toronto Locomotive Works. The first real railway boom in Ontario began with the passage of the Railway Act in 1849. The act gave parliament the power to invest and provide money to construct railroads under certain conditions. And this should come as no surprise as many of the members of Parliament were also knee-deep in the early railway industry. The Act stipulated that a railway corporation must promise a 6% return on the bond, built 120 kilometres of track and construct it to the Provincial Gauge, with the tracks set 5′ 6″ apart from one of the many types broad gauge railroads. For Ontario, the stage was set for the biggest shift in transport since the arrival of the Welland Canal.