If you haven’t heard of the small community of Petrolia, that makes perfect sense, it seems a bit out of place here in Ontario. But this is the area credited with kicking off an early oil boom in Ontario and within the British Empire. While a shadow of its former glory, the name and legacy live on as part of Canada’s role as a major exporter of raw resources.

Nikon FM – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 (Yellow-12) – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-100 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 7:30 @ 20C

Back thousands of years, the Attiwonderonk, Anishiabewaki, and Mississaugas made use of the sticky tar-like substance through the region to help with waterproofing their canoes. The area remained the territory of the Mississaugas until the Canada Company came calling in 1827, acquiring the land under Treaty 29 in 1827. The area became part of Lambton County and the Enniskillen Township. Settlers to the region worked the land as farmers until industrialist Charles Nelson Tripp began purchasing large areas of the township to exploit the bitumen in creating asphalt. Tripp petitioned successfully for the creation of the International Mining Manufacturing Company in 1854. And Tripp’s products earned world renown when they went on display at the 1855 University Exhibition in Paris. Tripp promptly made the contract to produce enough asphalt to pave the city of Paris. Sadly, while Tripp rode high on the initial success by 1857, he had been forced to sell off a majority of his holdings to pay off creditors. Among those creditors, James Miller Wilson, who sought the same bitumen but to create lamp oil, but when Wilson began digging a water well, it wasn’t water he found but oil. Oil Springs formed quickly and attracted many prospectors and surveyors to the region, one being John Henry Fairbanks. Fairbanks struck it rich with his Jerker Line system, steam-driven oil pumps and formed Fairbanks Oil in 1861. Further north, more oil patches were discovered, resulting in a second boom by the middle of the decade. The settlement of Petrolia grew overnight and was incorporated as a town in 1866. Fairbanks even led the charge to build a privately funded railway branch line to the Great Western line in Wyoming, which Great Western took over that same year. Soon thousands of barrels of oil were pouring out of the ground, but these early methods created large amounts of wasted resources. A second boom came in 1898 and a third in 1938, only lasting a few weeks. Hard Oilers, those who were born, raised and worked the oil fields, became world-renowned, and some eighty countries owe their oil industries to the workers of Petrolia. During the second world war, with the oil boom over, the town switched to industrial manufacturing; the presence of two rail lines certainly helped move products and materials out into broader markets. While today the community rests on the laurels of the past, oil and manufacturing remain a primary economic driver along with the history and the beginning of the oil industry in Canada. And thankfully, the community has done a great deal to ensure the preservation of the past.

Nikon FM – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 (Yellow-12) – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-100 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 7:30 @ 20C

Nikon FM – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 (Yellow-12) – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-100 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 7:30 @ 20C

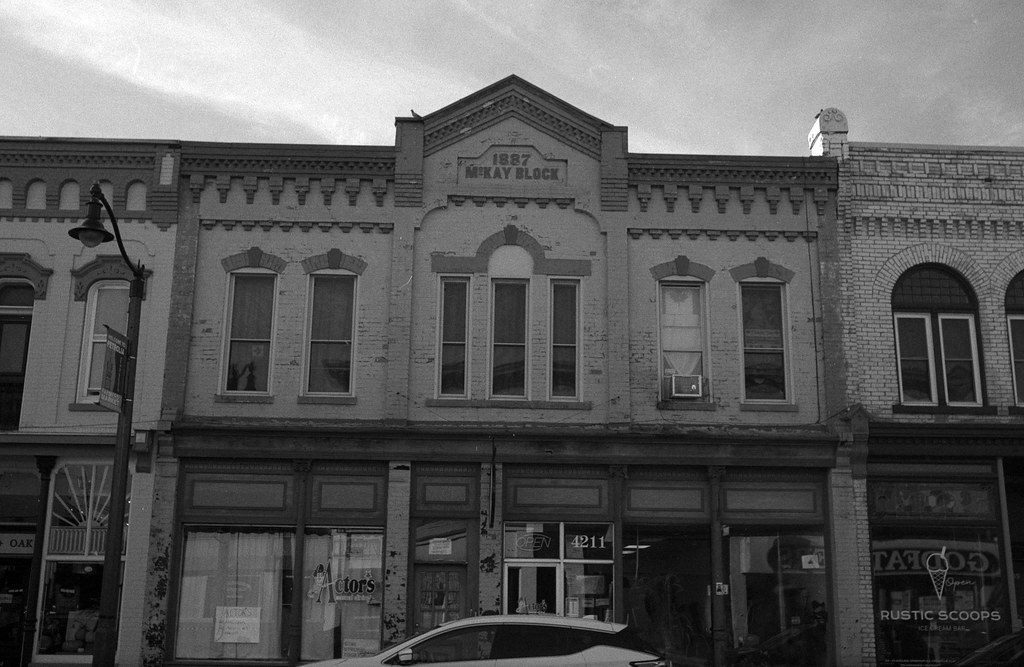

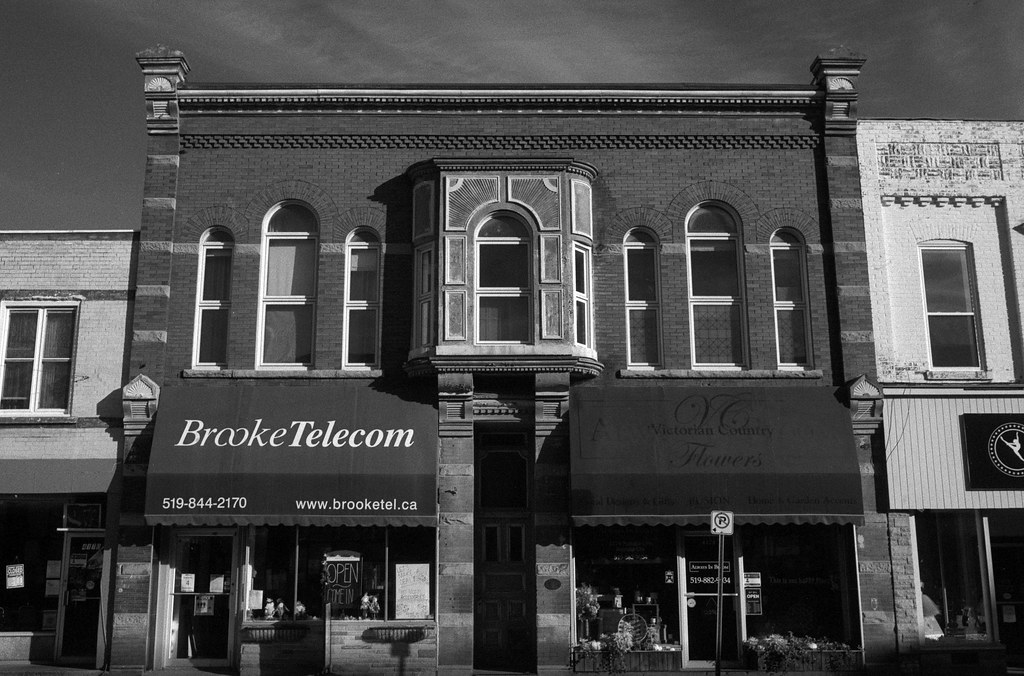

I’ll admit, this week was another hard one to figure out which images to include because I ended up with a large number of keepers. There were so many notable buildings downtown and even more that I realized that I missed because they were off on side streets. I should have done some more preparation as the local historical society does have a walking tour. But even sticking to the main road netted several impressive buildings from the stunning 1903 train station and the spooky Fairbank’s house or Sunnyside Mansion. An old hardware store and commercial blocks in various states of repair all show that the town once sat on a pile of wealth. Sadly I did not see the original oil fields (the gate was closed) or any of the original businesses, so I could not include anything like that. Like any of these trips, I certainly have Petrolia on my list of places to revisit in the future.

Nikon FM – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 (Yellow-12) – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-100 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 7:30 @ 20C

Nikon FM – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 (Yellow-12) – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-100 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 7:30 @ 20C

I had to keep it simple as I was working with a large camera loadout when visiting Petrolia. This week, I decided to stick to an old favourite, the Nikkor 35mm f/28 with a yellow filter. While the lens worked, I probably could have gotten away better with either the 28mm or 24mm in some cases. Although these couldn’t work for all the images, the compositions would have been too broad in some cases. I probably could have gotten away with having that second lens in the bag, but I honestly didn’t want to be swapping around lenses when I tried to keep walking through town. And I was then giving the film a one-stop over-exposure shooting it at ASA-100 rather than ASA-200. This allowed me to shoot with good shutter speed and aperture to keep the lens in that sweet spot of f/8. For development, I had enough Pyrocat-HD left over from the railroad project to run the film through that a developer. I also went for the first time with a two bath fix, the first being TD-4 designed for use with Pyro developers and won’t affect the stain. Then I ran the film through my regular Kodafix, thanks to Mat Marrash for helping me out with how long to do both fixing stages And the results they speak for themselves, this is precisely how I wanted the images to turn out, and the light and weather that morning were perfect for what I wanted. The images were sharp, gritty with a tonal separation to die for, an ideal match for an old oil town.

Nikon FM – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 (Yellow-12) – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-100 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 7:30 @ 20C

Nikon FM – AI-S Nikkor 35mm 1:2.8 (Yellow-12) – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-100 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 7:30 @ 20C

Next week Heather and I took a trip back out to Centre Wellington and the historic village of Fergus, so coming along with us!