Canada’s history with the treatment of mental health is long and sorted. And while we’ve made great leaps forward, often, many of the historical institutions have gotten lost and replaced along the way. Not that those who were patients in such facilities in the past would want a reminder standing out to them every day. While the Queen Street Asylum is long gone, replaced by the far more modern CAMH facilities, the asylum at Amherstburg has reverted to the historical configuration as a War-Era fort; even Mimicoe is now being used as a college campus. When I was deep into Urban Exploration, exploring mental asylums were a right of passage. While Canada only host a handful of massive Kirkbride styled facilities, and of those only a couple survive, unlike in the United States, if you were in the community and the circle of trust, there were some locations. And today, I’m looking back at my first experience with a Mental Hospital, the Muskoka Regional Centre.

Tuberculosis or the white plague has been around since the days of the ancient Egyptian kings and even written about by the great historians of the Roman Empire. But what does TB have to do with the Muskoka Regional Centre? Everything actually, the entire history of the Centre is tied to the treatment of TB in Canada. The earliest form of treatment of TB in the world was through isolation, usually in a place of high elevation and clean air. Known as Sanitariums, the first one in the world opened in Germany in 1854; it was also in Germany that the infectious bacteria was isolated in 1882. In Canada, the fight against TB became the personal mission of noted publishing giant William Gage. Gage, a key founder of the National Sanitarium Association, investigated a site to build a TB Sanitarium in Canada. While many were eyeing Toronto, the small northern Ontario town of Gravenhurst stepped up. The town offered up 10,000$, which was added to the 25,000$ offered up by Gage. The Muskoka Cottage Hospital opened in 1897; the high altitude distance from Toronto made it ideal for the treatment of TB. While the main cottage hospital was a payment facility, in 1902, a free hospital opened a short distance away. A fire in 1920 destroyed both the cottage and the free hospitals, but they were quick to rebuild. The new modern facilities, known as the Gage Complex, opened up in 1923. The complex had beds for 444 patients, surgical suites, laboratories, and support facilities. A second patient building, the Barbara Hayden, would be added in 1936. The discovery of Streptomycin in 1944 allowed for the treatment of TB in an urban environment without the need for isolation. The need for the Muskoka Sanitarium declined through the war and post-war period until it closed in 1960. The hospital reopened as the Muskoka Regional Centre, a satellite to the Orillia Regional Centre and focused on female patients. The place was a nightmare from the start, numbers were too much for the ageing buildings, and staff numbers were far too low. Muskoka houses anyone from those with serious mental illnesses to developmental conditions and disabilities. These resulted in a severe lack of care and abuse of the patients by those in authority. It became so bad that a 1985 report called for a zero admission policy, although the use of such places had declined since the opening of smaller group home support for many patients who would have gone to such hospitals. Muskoka Regional finally closed in 1994, although it would come back into the spotlight in 2015. A lawsuit against the government of Ontario unearthed old wounds. It resulted in a multi-million dollar payout to the victims of abuse at Muskoka who were housed here from 1973 to 1993.

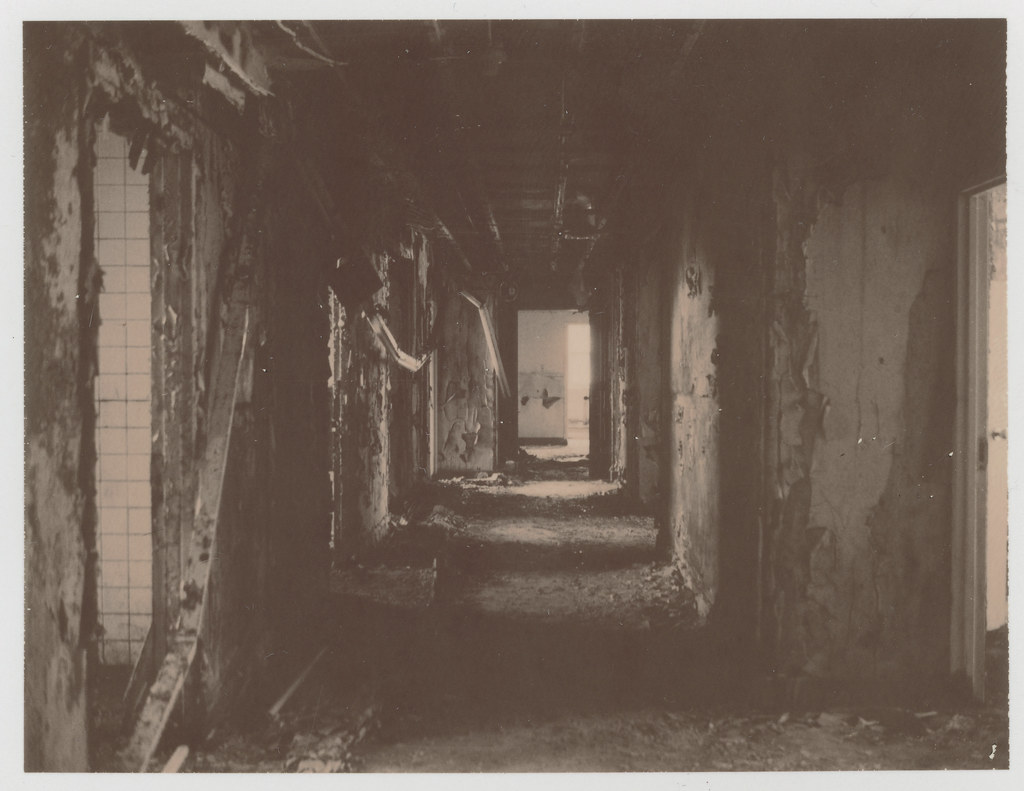

I can remember my first trip there in 2006, meeting up with a group of explorers that I had only met online. While I had missed the first “Sani-Tour”, I was determined to make it to the second one. This was also back when you could only go certain times of the year when the OPP wasn’t using the site for training purposes. Meeting up in a large public lot in Gravenhurst proper and travelling in a smaller number of vehicles onto the site. Working our way up to the site, I stood in awe of the Gage Complex; it was my first institution, having mainly explored industrial and houses by this point. We also didn’t have to worry about security either. However, I remember dog kennels at either the second or third trip. Upon entering, that wonderful musty smell of a long-abandoned building was left exposed to the elements. Good chance it was pretty deadly to be inside for any time. I had my respirator with me for that first trip like any good new explorer does, but I left it at home when I started working with SLRs; these were the days before live-view. The Centre is also the first location I explored where I got a sense of the spirit of place. It’s hard to explain fully, but each time I went inside, I felt a great wave of sadness, at the time, I had no idea of the suffering that went on in this place. Of course, this was all before the lawsuit against the government took place that it made sense. One of the more interesting notes is that eventually, the police stopped using the location. Access could be had year-round if you had the courage to do so because locals started to get wise to people moving in and out of the old property. Yet somehow my luck didn’t run out, even exploring the site with a rather large group in the summer of 2011. The irony is that when I was there with the smallest group, including two from out of the country, we ended up getting caught. It was our fault, we were pretty fearless, and snow left a lovely trail of footprints; of course, we also weren’t expecting on-site security.

There are only a few locations like the Muskoka Regional Centre where I can show the breadth of my photographic journey. The location is also the first where I shot film at an abandoned location in any significant way, almost from the start. In fact, the first trip to the Centre was in 2006 with a simple 4-megapixel super-zoom camera. I can see the beginning of my enjoyment of leading lines, although my compositions were still a little off and limited by the camera’s capabilities. Plus, my understanding of exposure is certainly lacking and dependent on the camera for most settings. By the third trip, my camera had been upgraded to a D70s; I was working with aperture priority and manual modes to get longer exposures and letting my eyes determine exposure with the help of the in-camera meter. By 2010 my kit had expanded to include the D300 and a 14-24mm f/2.8 lens; I was also starting to get better with my work in film and exploring how to use the square format in my exploring. Compositions improved significantly with more attention to leading lines, keeping things straight. Focusing on details using handheld, shallow depth-of-field. My Rolleiflex 2.8F and Kyiv 88CM provided terrific results and experimented with Type-100 Polaroid Film. Probably some of my strongest work came out of my trips to the Centre in 2011 and 2012.

Sadly, there was always a chance of being caught like any trip. And while we certainly enjoyed many years without active security on-site, the final journey that I took ended up being in the winter, and security had been positioned on-site. We had the OPP called on us. Thankfully we made it out with one ticket issued and threats of further action should we return. And I stuck to my promise never to go back. Sadly I never made it into the other building on site, the Barbra Hayden. Still, the Gauge Complex provided a tonne of options to see and photograph and given that I visited the area over six years with the only incident happening at the very end, I think that’s a good track record. While I did only include film photos in here, you can head on over to Flickr and check out all my images including some of the cringe-worthy early shots.