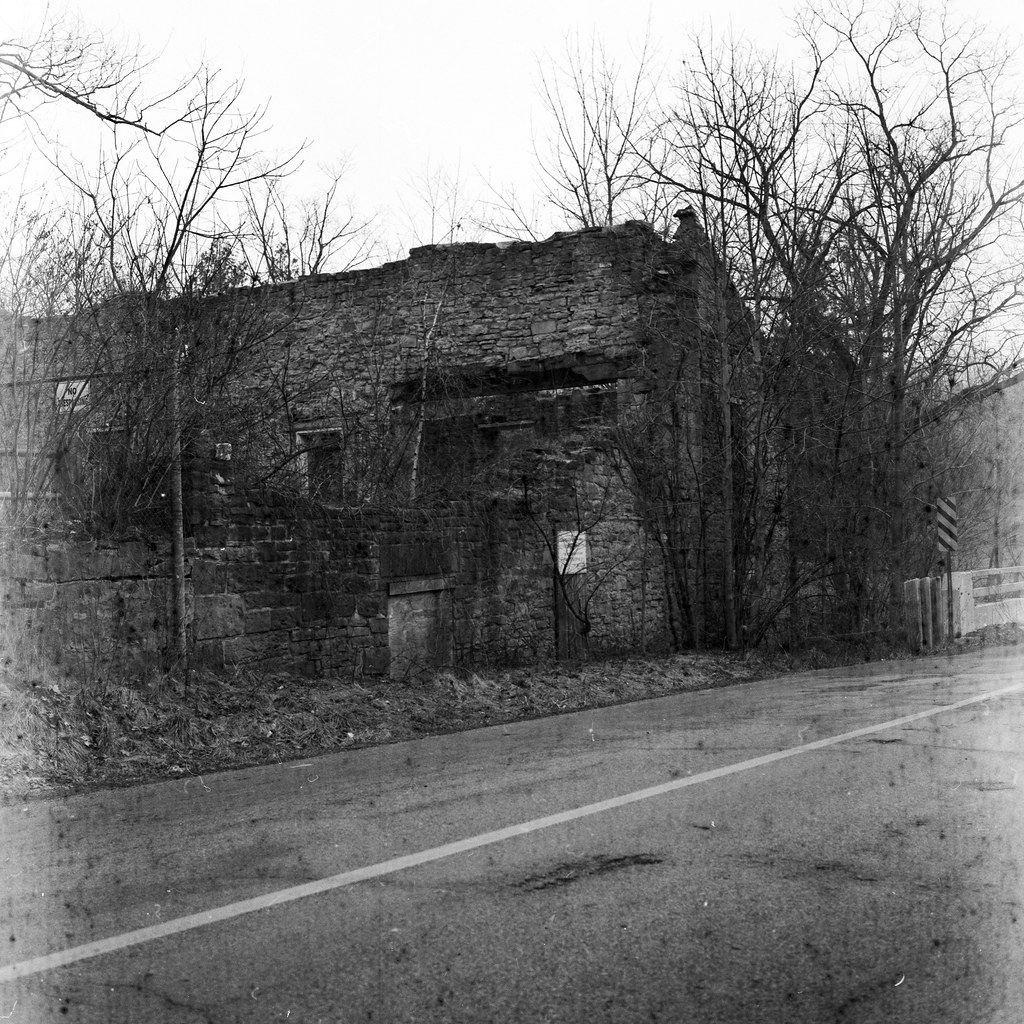

It’s been a long time since I thought about the Darnley Grist Mill. It wasn’t until I saw a memory pop up on Facebook that I was heading out to kick off the start of my War of 1812 project, which included a stop at the Darnley Grist Mill. I ‘discovered’ the location in a book with a list of different sites related to the Anglo-American War of 1812. Oddly enough those shots never went into the project despite the connection of the mill to the war. But despite touching on the subject of mills and local supply lines, I never used those images. Having a free day, I headed out to check out the ruins with my Rolleiflex and a roll of ORWO Pan 100, basically rebranded Forte film.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

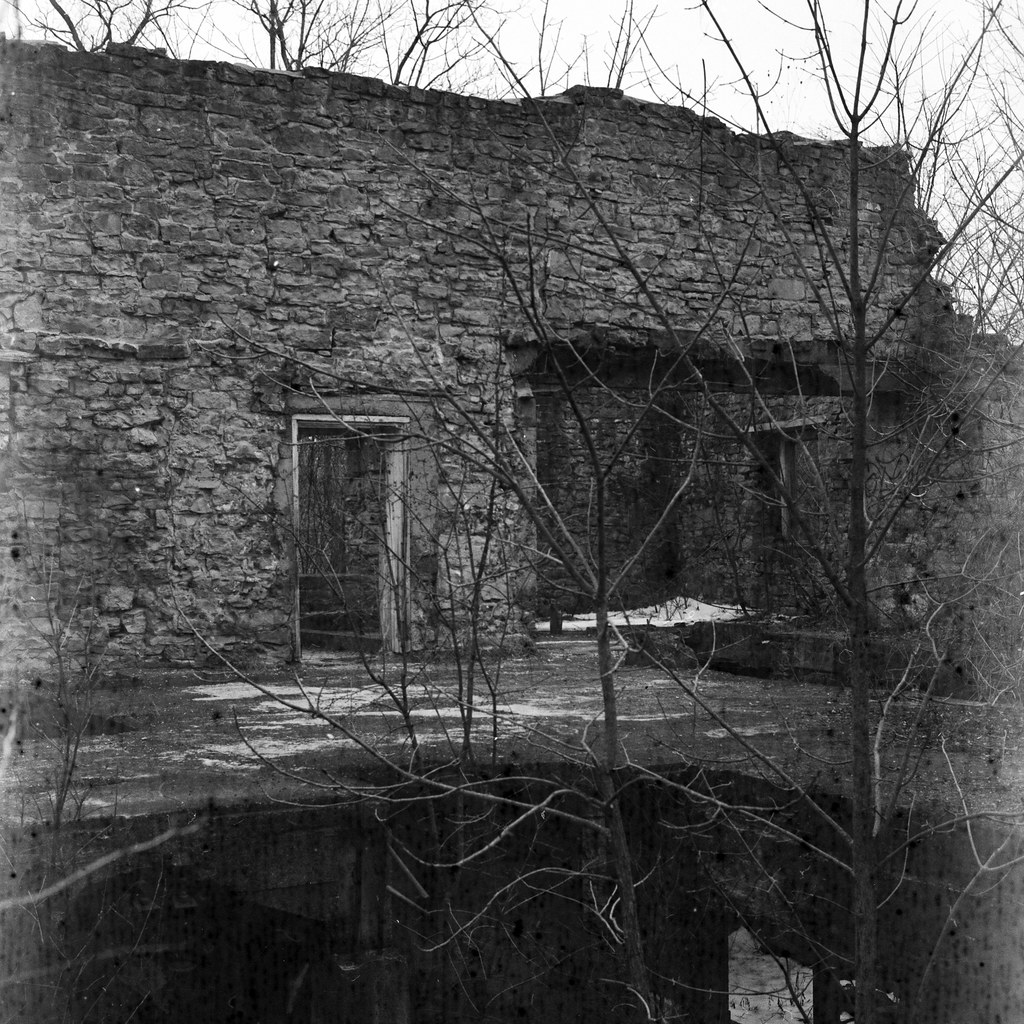

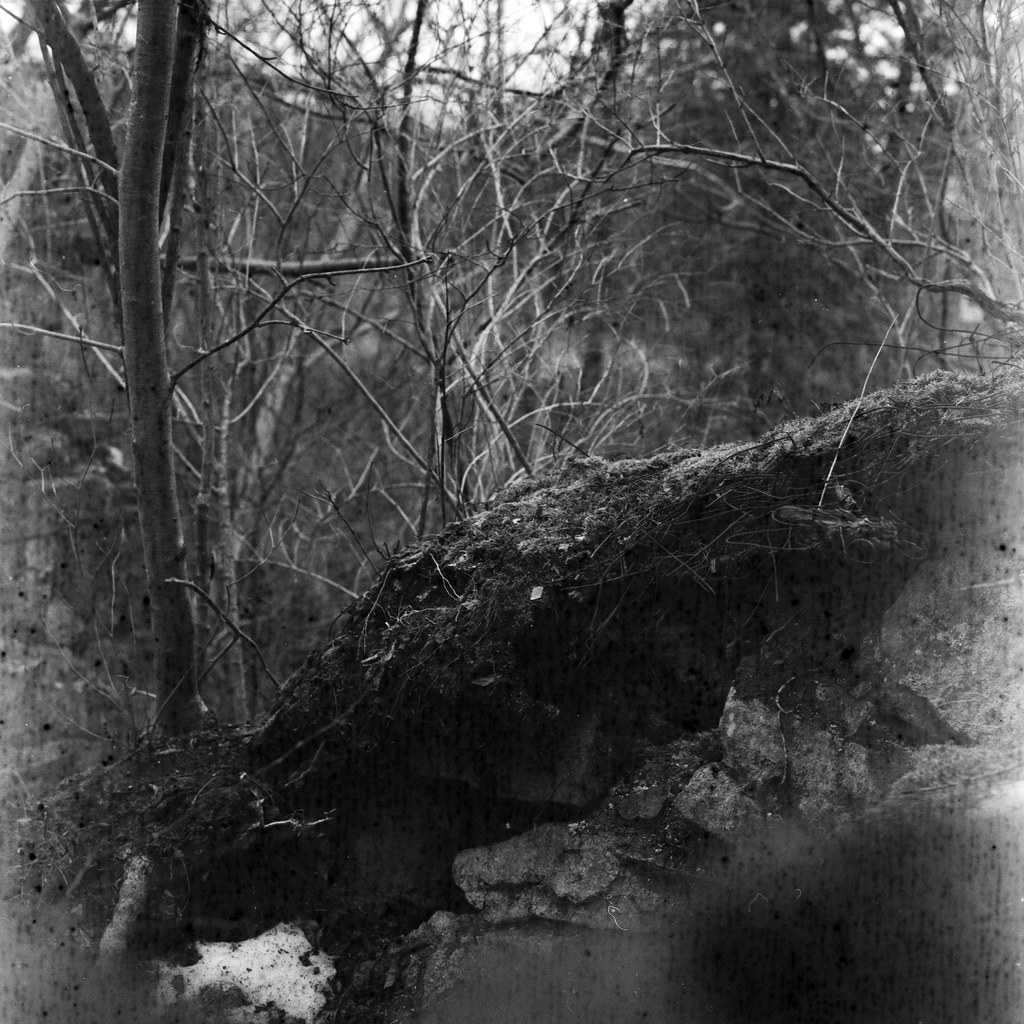

Located above the townsite that would become Dundas, Spencer’s Creek tumbled down several cascades before falling over the edge of the Niagara Escarpment. This stretch of running water formed the background for some of the area’s earliest industries. Ceded to the Crown in 1792, the same year the area was surveyed for development. Several mills sprung up near various cascades, and small settlements sprung up around these mills. James Crook purchased one of those lots in 1811. Crook was a relatively successful merchant who emigrated to the Thirteen Colonies in 1791 and relocated to Upper Canada in 1795. Construction of a stone grist mill started in 1811 and saw completion in 1813. He named the cascade and mill Darnley, after Lord Darnley, a famous relation to Crook. During this time, Crooks served as the Captain of a local militia company, serving alongside British Regulars and General Sir Isaac Brock at the Battle of Queenston Heights. His grist mill began operating in 1813 and produced flour for the British Army; Crooks completed his home in 1814 and moved in near his mill (a site further up Spencer’s Creek); as a local business owner, he served on the jury for the Ancaster Assizes that year. Following the war, he expanded the operations, completing a distillery, tannery, cooperage, woollens and cloth mills. But the real jewel was in 1826, with the aid of the Barber family, completed the first paper mill. By 1829, the small settlement of Crooks Hollow also had a series of workers’ houses and an inn. The Hollow thrived through the middle of the Century. As Dundas grew below into a more significant manufacturing centre, the demand for water supply stripped the ability to produce the needed power. Crooks sold off the paper mill in 1851 to focus on the other mills. The paper mill passed through several hands before ending up in a partnership between James Stutt and Robert Sanderson. Crooks would pass away in 1860, and the remaining businesses were also purchased by Stutt and Robertson, who converted all the mills to produce paper. Despite the general decline in the area (thanks to being bypassed by the railway), the original mill continued to operate as a paper maker despite several others being demolished or destroyed in a fire. Stutt bought out Sanderson in 1878 and converted the mills to run on steam power. A move that would result in a deadly explosion in 1885, killing two and causing massive damage. The original mill was rebuilt and operated as a paper mill, and its production facilities were leased to other businesses. The Greenville Paper Co. continued to lease the mill well into the 20th Century, even replacing the wooden floors with concrete ones in the 1930s. However, in either 1934 or 1943 (depending on who you ask), the mill burned down and never was repaired. The ruins would languish as the local government would move to replace some of the control dams in the area; in 1958, they became part of the local Conservation Authority. Since then, the mill ruins have been stabilised, and public access has been restricted. There are efforts to have the mill ruins registered as a Heritage Site, but those were discussed back in 2012, and ultimately decided against designation.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

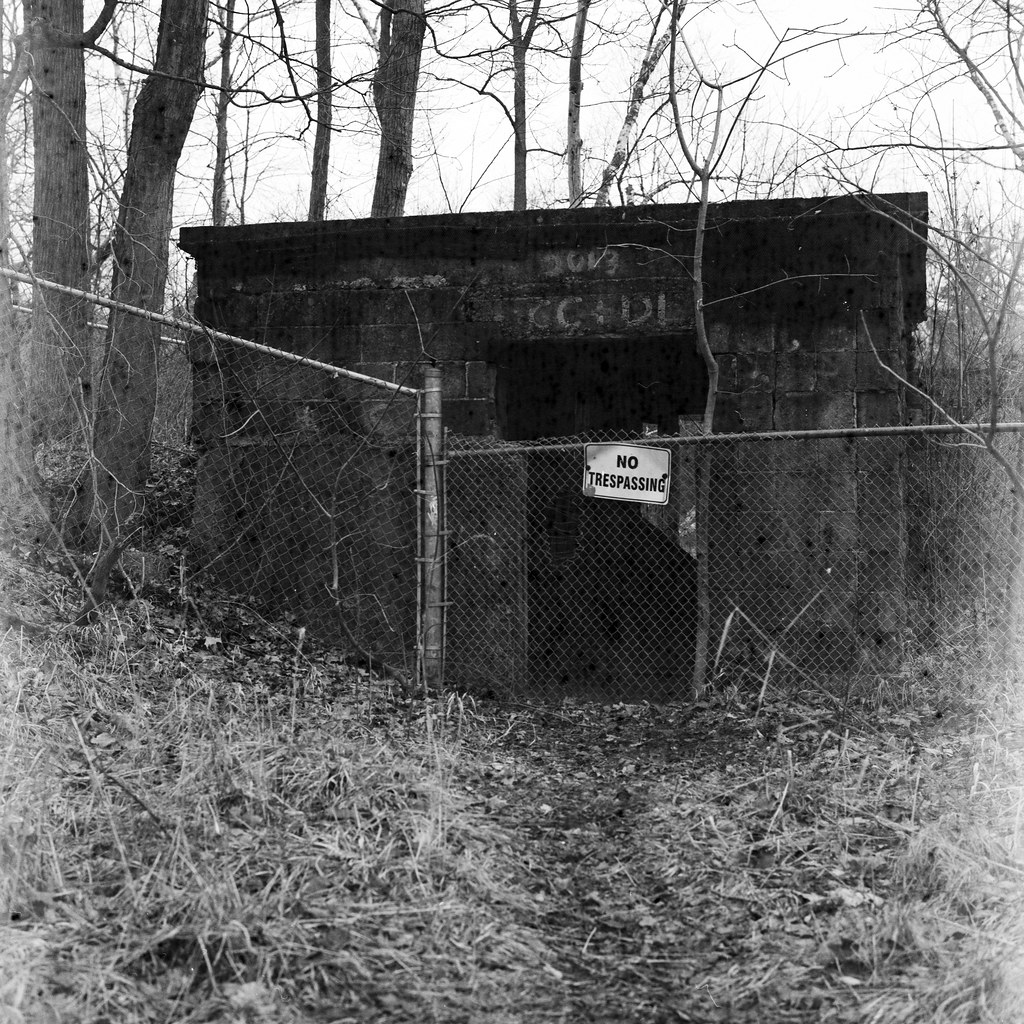

The day I was out proved to be foggy, but after stopping in Dundas, the fog was starting to burn off when I climbed out of the valley. Although it was still present in a limited way by the time I got onto Crooks Hollow Road. My original plan had been to park my car at the Crooks Hollow Conservation Area, as parking along the narrow, winding road was not the best idea. The trouble with those passive conservation areas is that they are seasonal, and the lot was closed and gated. There is a small part near the ruins where I could park off the road, but it is also an emergency entrance for the Christie Lake Conservation Area. While I originally wanted to get the D750 out, I left that in the car and only shot the Rolleiflex; I could shoot twelve frames faster than worrying about more with the digital. I started with exterior shots, but getting into the ruins themselves was impossible with the new fence on the property. At least until I found a way in, and after checking out the floors (thankfully concrete), I could get beyond the fence line. While inside, a couple of people, whom I had initially thought were conservation employees, were on the other side of the fence. They turned out to be locals walking their dogs and looking at the ruins of the plaque; I wandered out and greeted them before getting back into my car.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – ORWO Pan 100 @ ASA-100 – FPP Dalzell76 (Stock) 6:30 @ 20C

While I’m saddened that the mill ruins are not on the list to be designated, it makes sense. Despite the historical significance, they are in far worse shape now, over ten years from when I last visited. But efforts have been made to keep people away from the ruins. The ruins themselves are dangerous; while there are some stable sections, there are whole sections where the floor is gone, and you’re falling at least three storeys before hitting the ground. There is also the fact that to get past the fence, you are getting close to the running water of Spencer’s Creek. I’m not promoting trespassing, but if you are interested, do it safely. If you are interested in checking out the mill ruins, they are located at 43.276468, -80.006402 along Crooks Hollow Road.