The simple matter was that neither the Americans nor the British were ready for a renewed conflict in North America. The British were fully committed to the invasion of Europe in the Peninsular War, secured Portugal, and invaded French-occupied Spain when the war broke out in North America. While many in the United States wanted to teach the British a lesson, they were not in the best position to fight a war. Even as the declaration of war made its way through the US Congress, the plans and preparations for the war were being made. The American plan was a coordinated three-prong assault across the Detroit River, taking Amherstburg, another across the Niagara seizing Fort George and a third to capture Montreal. All while Commodore Isaac Chauncy would pin the British squadron in Kingston. The trouble was that the American government still had a distaste for a large standing professional army, which numbered 7,000 officers and men but, in theory, could bring up 450,000 militia troops. In both cases, the officers in charge were political appointees who, in some cases, had not seen any actual combat since the American Revolution. There were also a small number of Indigenous peoples who were allied with the Americans. The US Navy focused mainly on the eastern seaboard. It consisted of 5,000 officers, marines, and sailors, most of whom were warships, the heavy frigates first authorised at the end of the last century. The squadrons on the Great Lakes were small, with only one or two warships and a smaller number of gunboats. In British North America, the army numbered around 10,000 regular and fencible troops and officers, all highly trained and professional soldiers, but could only call up 4,000 militia troops and many Indigenous allies. The Royal Navy maintained 11 ships-of-the-line, 34 frigates and 52 smaller vessels covering the Atlantic and Caribbean posts. On the Great Lakes, they maintained small squadrons at Kingston and Amherstburg but relied on smaller ships operated by the Provincial Marine, a naval militia force that focused mainly on transport rather than fighting. Since Governor-General George Prevost and General Isaac Brock came to their posts, both men had improved local militia training and rebuilt some of the defences along the frontier. General Brock had gone even further by establishing lines of communications by using civilian agents, mainly fur traders, to quickly move messages across the vast distances between the more remote posts in the province. But Brock also had to deal with poor morale among the British regulars, both the men and officers who had heard of great battles in Europe, and even Brock was feeling the call to Europe to earn his laurels.

Sony a6000 + Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

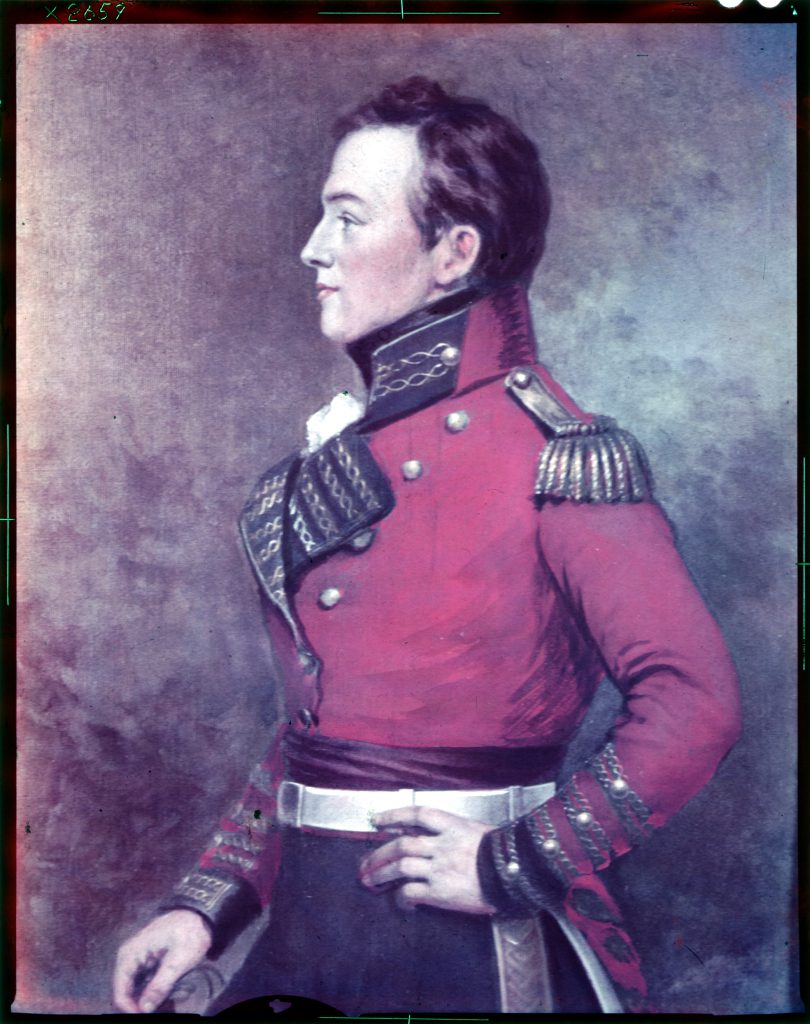

The ironic thing is that two days before American President James Madison signed the declaration of war into law, the British Parliament, which was trying its best to appease the Americans, announced the suspension of the economic warfare measures that had rattled them. Even though it would take months for news of the American declaration of war and the suspension of the Orders in Council to reach their appropriate capital cities, news of the declaration arrived in British North America much faster. In Quebec City, the colonial capital, Governor-General George Prevost was already ordered to fight a defensive war and set about boosting the garrison. In Halifax, the Royal Navy deployed their ships to defend the eastern holdings of the Empire. General Isaac Brock took a different view of his orders to fight a defensive war in Upper Canada. Brock felt that a first strike against the Americans and building a beachhead would make for a better defensive strategy. He sent word north to Fort St. Joseph, near Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, through one of his many agents, a fur trader named Robert MacKay. The orders were addressed to the post’s commander, Captain Charles Roberts, to take his regular troops and any allies and retake Mackinac Island, securing the straights between Lake Huron and Lake Superior and ensuring the trade lines between the northern and southern holdings. Brock also sent work to Fort Amherstburg and east to Kingston and beyond to prepare for war and seize any American vessel that got too close. General William Hull, appointed commander of the Armies of the Northwest, had been marching north from Cincinnati since May, laying a supply road and building depot forts up through Ohio and, by June, reached the Maumee River. General Hull and his army of militia and regular soldiers had no idea that the President had signed the declaration of war, so Hull ordered his baggage, the engineering tools and all his papers, including the American war plan, loaded onto Cuyahoga Packet and sailed up to Fort Detroit (this particular fortification is also referred to as Fort Shelby or Fort Lernoult), while the main body of troops continued on foot. As word of the war spread through the United States, many supported the move; others, those from the Federalist Party specifically or in the New England states, were less than pleased. One such person, Alexander Hanson, a member of the Federalist Party for the State of Maryland, published several anti-war columns in his newspaper, the Federal Republican. These columns raised the ire of local pro-war persons who formed a mob and, on 22 June, surrounded the paper’s offices, breaking in and destroying all the presses, paper, ink, and typeset and then taking down the entire building. What followed were several days of violence between pro-war and anti-war persons in the city of Baltimore before order was restored. It was not until 2 July that General Hull received word that war had been declared, and he made haste to reach Fort Detroit to begin preparation for the invasion of Upper Canada. As the Cuyahoga Packet sailed into the Detroit River it was intercepted by the H.M. Brig General Hunter commanded by Captain (Lieutenant) Frédérick Rolette, who being aware of the war, captured the American vessel without resistance. Upon discovering the personal belonging of General Hull sent them ahead to Fort Amherstburg. The garrison’s commander, Lieutenant-Colonel T.B. St. George, after learning of the American war plan, sent word to General Brock at Fort George in Newark (Niagara-On-The-Lake, Ontario) and asked for reinforcements having only 300 men of the 41st Regiment of Foot to defend against a potentially more significant American invasion force. Three days later, General Hull arrived at Detroit to find his post in disarray. Most importantly, he lacked the critical supplies to invade Upper Canada effectively. Despite learning of the ship’s capture carrying his papers, many among his staff pushed for an immediate invasion of Upper Canada. The supplies they said would be taken from the British as the local population was ready to rise and join the Americans, welcoming them as liberators rather than standing against them as invaders. Captain Roberts had also been caught in the middle of conflicting orders from Brock and Prevost, all while gathering a large number of fur traders, Metis, and Indigenous warriors at Fort St. Joseph to supplement his force of 47 hard-drinking regulars from the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion. The gathering did not go without notice, and one trader would pass word of this on to Lieutenant Porter Hanks, the American commander of Fort Mackinac.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

It was a stance that some in the United States were clinging to; even the former President, Thomas Jefferson, penned that the capture of Upper Canada would be a mere matter of marching. It also set many in the colonial parliament in Upper and Lower Canada on edge that it was still possible that many in the provinces would rise and join the Americans. While most of the population of Upper Canada were loyalists or the descendants of those loyalists who fled from the United States during the Revolution, many Americans had come north to call Upper Canada home. The other big question marks were the French-Canadian population in Lower Canada and the Indigenous peoples. Under these auspices, General Hull crossed the Detroit River on 12 July north of the village of Sandwich, near what is today the Hiram Walker Distillery in Windsor, Ontario. Marching south to little or no resistance as the militia and any regular troops fell in the face of a large invasion force. General Hull set himself up in the home of François Baby, using the brick home as his headquarters, while sending his troops further south into Sandwich, ordering them to hold there. The lack of meaningful resistance only propelled the idea that many in Upper Canada were willing to play an active role in their liberation. Hull issued a proclamation declaring that the local population were not accessible from the tyranny of the British Crown and that any volunteers willing to join the further liberation of the Canadas would be welcomed into his army. He also warned off anyone from trying to resist and then promptly ordered raiding parties in the surrounding region to collect supplies. While Hull’s army received some volunteers, it was not the welcome he had expected. His actions, if anything, sent the local militia to the ground to defend their homes against American raiding parties. Upon learning of Hull’s invasion, Brock took action; rather than override his superior’s orders, he sent word to Captain Roberts to use his digression in attempting to capture Mackinac Island. In the meantime, General Brock headed for the provincial capital of York (Toronto, Ontario) to meet with the executive council. While Brock is often portrayed as the acting Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada during the first year of the War of 1812, the governor was Francis Gore. Brock was titled as President of the Executive Council. The ruling council of the province gave him enough power to call up the rest of the provincial militia in the face of a hostile invasion. At Mackinac Island, Lieutenant Hanks, having received no official communications from the south in nine months, faced a dilemma: the news of a large gathering of fur traders, Métis, and a mixed force of Anishinaabe, Odawa, Mamaceqtaw, Oceti Sakowin and Ho-Chunk at St. Joseph Island certainly was something to be concerned about. Hanks commanded a garrison of 60 men, mostly artillery gunners, most of whom were unfit for duty, and a small force of militia comprised of islanders. Hanks ordered Robert Dousman, an officer in the militia and a fur trader known through the region, to head out and investigate. Captain Roberts, knowing that any delay would cause his force to drop in numbers and having the clearance to use his best judgement, set out with a mixed force of 600 aboard a commandeered North-West Trading Company Brig, the Caledonia, with ten additional bateaux, and seventy war canoes on 15 July.

Nikon F4 – Nikon Series E 28mm 1:2.8 – Agfa APX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Nikon F4 – Nikon Series E 28mm 1:2.8 – Agfa APX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Nikon F4 – Nikon Series E 28mm 1:2.8 – Agfa APX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Against all the odds, Dousman would run into Captain Roberts while en route to investigate, realising he could not escape. He surrendered and was brought aboard the Caledonia and questioned by Captain Roberts. Dousman was surprised to hear that a state of war existed between Great Britain and the United States and also confirmed that such a word had not reached Mackinac when he departed. Dousman agreed to help Captain Roberts in exchange for the promise of the safety of the island’s civilian population. Dousman also provided a rundown of the fort’s armaments, stating that it was lightly defended on the northward side and that only one mounted gun could reach the harbour. General Hull’s officers started questioning their ageing commander; he insisted on waiting for artillery before pushing an attack on Fort Amherstburg. Hull did agree to send a patrol in force on 16 July south to probe the British lines. Lieutenant-Colonel Lewis Cass marched a mixed force of Ohio Militia and elements of the 4th US Infantry, meeting a British outpost at the River Canard, north of Amherstburg. The outpost, commanded by Lieutenant Clemow with a detachment of the 41st Regiment and Essex Militia, had no chance of fighting off the larger American force and retreated, fighting where they could. But in the confusion, two privates, Hancock and Dean, were left on the other side of the river. The two professional soldiers continued to fire until they were both injured and were taken prisoner. Both men would die of their wounds. The British retreat from the Canard left the way open for Hull to march without resistance on Amherstburg, but he refused to move still. And many under his command began to speak of having him removed. Before dawn on 17 July, Captain Robert’s force landed at the island’s northern point. Making his way inland to the island’s highest point overlooking the fort, he brought the three cannons aboard the Caledonia, manned by a small force of Royal Artillerymen. Dousman, playing his part, snuck around and into the small town, collecting the civilian population and allowing them to get into hiding, bringing local leaders back to Roberts. At dawn, reading the high ground, Roberts ordered a cannon shot over the fort. The sudden blast alerted the garrison, who scrambled, and Lieutenant Hanks found the high ground occupied by a large number of British and Indigenous troops. One of Robert’s officers, Dousman, and several islanders approached the north gate of the fort under a flag of truce, demanding the fort’s surrender. The islanders exaggerated the number of indigenous troops with the British and repeated the warning that Roberts had no way to control them should the walls be breached. With no other choice, Lieutenant Hanks accepted the surrender and turned over his sword to Captain Roberts. Captain Roberts quickly moved to secure the two ships in the harbour, leaving the American flags flying, which affected the capture of two other vessels inbound from Fort Dearborn. Captain Roberts was true to his word; there was no looting, and anyone willing to take an oath of allegiance could stay, and most did; those who didn’t were allowed to leave with the garrison and head south to Detroit. Captain Roberts did expropriate the entire armoury and government storehouses but left private warehouses alone and purchased supplies from the civilians.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:30 @ 20C

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

The British Parliament in London had been in the process of permanently repealing all their economic warfare measures since early July. Still, it was not until 23 July that the provisional suspension became a permanent repeal of the Orders in Council. Word of the declaration of war reached London on 29 July, while Parliament believed that when word reached President Madison that everything could be smoothed over, they still issued orders to blockade American ports, seize American ships currently in British ports and order their boats to travel by convoy. Ironically, during this interlude, the first group of reinforcements arrived at Fort Amherstburg on 26 July under Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Procter with several companies of the 41st Regiment. On 29 July, Lieutenant Hanks arrived at Fort Detroit with news that the British had captured Mackinac. But his actions to surrender without a fight resulted in his immediate arrest for cowardice and confinement. But Hanks also brought a warning that many of the Indigenous troops that helped capture the island were also heading south to join Tecumseh. Colonel Proctor brought orders from General Brock to disrupt the American supplies heading north to Fort Detroit. Hoping to boost his supplies, General Hull ordered Major Thomas Van Horne to take a force of 200 men south to the River Rasin and collect supplies left there. On 5 August, the column arrived at the creek near the Wyandotte settlement of Brownstown, where a group of Shawnees led by Tecumseh jumped the American column. While the American troops outnumbered the Shawnee, their attack’s surprise, speed, and violence gave them an edge. Major Van Horne’s militia took flight first, retreating in disorder, leaving him with only half his force. He had little choice but to retreat. The loss at Brownstown and the news of more violence against American posts by the Indigenous population saw General Hull send out orders to smaller posts to retreat to more extensive, better-defended posts throughout the Northwest. One such post, Fort Dearborn, commanded by Captain Nathan Heald, was ordered to retreat to Fort Madison. General Hull would attempt to bring another group of reinforcements north; Captain Henry Brush had been pinned down by a mixed force of regulars from the 41st, Essex Militia and Indigenous Troops under the command of Major Adam Muir. Sending a force of 670 men under Lieutenant-Colonel James Miller south to escort Brush north. Near the Wyandotte village of Maguaga, Miller’s column ran into Muir’s force blockading the road on 9 August. Miller ordered an attack with a superior force advanced under heavy British fire. Muir’s force seemed to be holding the Americans back under a group of Indigenous warriors in a flanking move through the woods, mistaken as American-allied Indigenous warriors. A militia group shifted their fire, and the warriors in the woods fired back. Despite this, Muir, seeing the American advance falter, ordered his light company to charge in with bayonets to chase the Americans off when the advance sounded on the bugle (which is how orders were delivered to the light and rifle companies in the British Army rather than drums), other company commanders mistook the command as a retreat and began to fall back. Seeing the British falling back, Colonel Miller reformed his line and pushed up, only to meet a reformed British line. Miller lost his nerve, pulled his men back, and camped out in the woods, digging in fearing an Indigenous trap for the next two days before falling further back. In the meantime, Muir received orders to return to Fort Amherstburg as General Brock and additional reinforcements were arriving.

Nikon F4 – Nikon Series E 28mm 1:2.8 – Agfa APX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Nikon F4 – Nikon Series E 28mm 1:2.8 – Agfa APX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Nikon F4 – Nikon Series E 28mm 1:2.8 – Agfa APX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

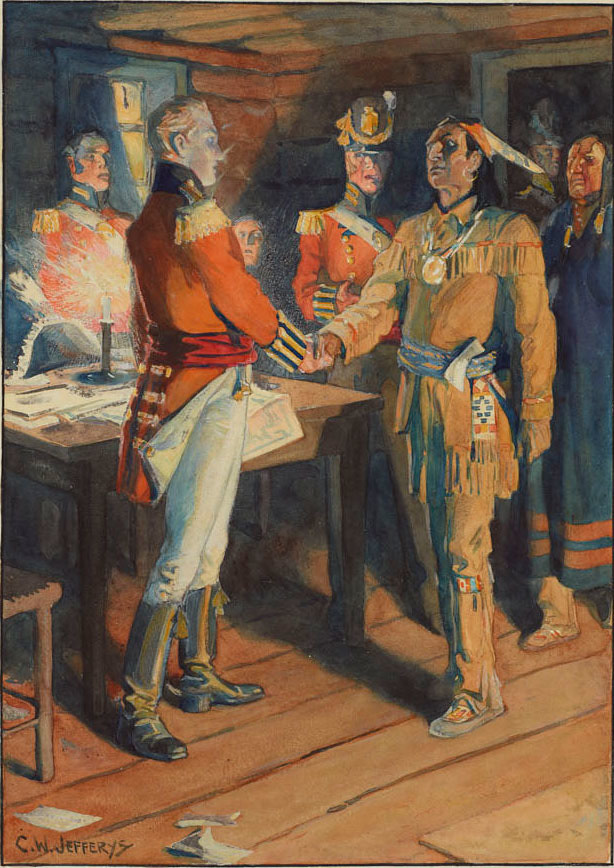

The last Americans left Upper Canada on 11 August; since 3 August, Hull had been pulling the garrison out, having achieved none of his goals. While word had reached President Madison that the leading cause of the war had been repealed by the British Parliament, Madison and the entire nation were fully committed to the war, and the avalanche had started. General Hull was not in a good place; his age, combined with illness and heavy drinking, forced him to hide behind the walls of Fort Detroit. General Isaac Brock arrived at Fort Amherstburg on 13 August and immediately made plans to lay siege and take Fort Detroit from the Americans. The trouble is that Hull’s army still outnumbered Brock’s, but Brock had a plan. First, he ordered a series of artillery batteries constructed across the river from Fort Detroit. He ordered the H.M. Sloop Queen Charlotte and H.M. Brig General Hunter upriver to add firepower. The storehouses at Fort Amherstburg were opened, and surplus coats of the 41st were distributed to the militia troops to give them the appearance of British regulars, and additional campfires were lit to again give the impression of more significant numbers. The real boost to Brock was the Indigenous troops; legend has it that when Brock and Tecumseh met at the Duff-Baby House in Sandwich, the two men immediately recognised the fighting spirit in each other. Tecumseh acted as a beacon; Indigenous troops came from Upper Canada and the United States to join the cause. Brock used the Americans’ fear of these warriors to their advantage and promised to ensure he would negotiate for a proper territory for an independent nation. The final piece of Brock’s scheme involved a letter that was to be intercepted by the Americans telling Captain Roberts at Fort Mackinac to stop sending more Indigenous warriors south as he already had some 5,000 at Fort Amherstburg. The number was vastly inflated, but it would undoubtedly put fear in the hearts of the American militia. Brock planned to open fire on the American fort and send a demand for surrender at the same time with a warning stating he could not control Tecumseh’s troops should the walls be breached. On 14 August, the guns opened up with the surrender demand delivered. But some hundreds of miles distant, Captain William Wells had arrived at Fort Dearborn back two (or one) day prior with a militia force and a group of thirty Miami warriors allied with the Americans to deliver General Hull’s orders. The post’s commander, Captain Nathan Heald, called the leaders of the nearby Potawatomi villages to inform them that he and his garrison would be leaving the fort the next day. The leaders asked if Heald would release the post’s storehouse to them upon their departure containing food, ammunition, weapons and alcohol. When Heald told them he would take the stores with him or destroy them, the elders said they could not control their younger warriors, and violence could ensue. Like many Americans of the age, Captain Heald did not hold the indigenous population in high regard and ignored the warning. On 15 August, the garrison departed Fort Dearborn. Heald and Williams commanded a garrison of about sixty men, a mix of regulars and militia, the thirty Miamis and twenty-seven civilians, including Captain Heald’s wife. Captain Wells approached the head with his detachment while the militia guarded the civilians and baggage train, with Captain Heald taking up the rear with his regulars. The column was a mile and a half away from the fort when a group of Potawatomi ambushed the column. The Miami allies vanished (although some reports say they turned on the Americans), and Captain Wells fought bravely, killing many before he was killed in the early moments of the action. Most of Well’s men and half of Heald’s detachment were killed. When the Potawatomi turned on the baggage train, the militia was quickly overwhelmed; Heald rode to reform what troops he could but soon found himself surrounded and surrendered, hoping for mercy. The prisoners were rounded up and marched back to the fort. There, the killing continued; only the intervention of a local fur trader saved the lives of Heald and his wife, who, once they were safely away from the post, were sent to Fort Mackinac and, from there, redirected down to Detroit.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Rollei RPX 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (Stock) 8:00 @ 20C

Nikon F4 – Nikon Series E 28mm 1:2.8 – Agfa APX 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

The British/American artillery dual lasted for almost twenty-four hours; it had chased General Hull back into his bottle and killed the unfortunate Lieutenant Hanks. The Americans were forced into shelter but also handed the British a few casualties. In the early hours of the 16th, General Brock began his crossing of the Detroit River; the plan was to surround the American fort on the three landward sides, cut off the single supply road heading south and dig in for a long siege. To achieve this, Brock divided his force into three brigades. The first was made up of a half-company from the Royal Newfoundland Regiment with the Kent and Lincoln Militia units, the second was a half-company from the 41st with the York, Oxford, and Lincoln militia units, and the third was the rest of the 41st and five artillery pieces manned by Royal Artillery Gunners. But the actual piece of psychological warfare was Tecumseh’s troops in the woods making as much noise as they could. So, when the American garrison woke up the following day, loud war cries came from the woods, and they found their fort surrounded by British troops. While Brock intended and had prepared for a long siege, word reached him that a column of American soldiers was coming up from the south, and he planned a direct infantry assault against the fort and sent a demand for surrender again. General Brock again reminded Hull that he would not be able to control the Indigenous troops in his command. It was enough to send Hull into a spiral, and despite his officer’s demands to fight back as they had a larger army (although poorly supplied), Hull accepted Brock’s surrender. But rather than going himself, he sent his son to deliver his reply and asked for three days to prepare. General Brock gave him three hours. Hull’s defeat was total; he had surrendered the entire garrison, the fort itself, a large swath of territory, and the column marching north. General Hull firmly defended his action as preserving and saving the lives of not only his men but the civilian population from horrendous death, but now he and thousands of American regulars and militia troops were prisoners. General Brock gained Fort Detroit, small arms, thirty heavy artillery pieces, ammunition, food, clothing, and the U.S. Brig Adams, which was taken into the Provincial Marine as the H.M. Brig Detroit. General Brock would leave Colonel Procter in charge of the region and head back to the Niagara region to meet the threat of an American army poised to invade across the Niagara River. Tecumseh would also remain in the west, with a great deal of indigenous warriors itching to engage the Americans again in battle. Little did he know that General Prevost had negotiated local ceasefires to prevent further actions with the possibility of peace (which was long past possible), using General Roger Hale Sheaffe as a go-between.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF Macro 100mm 1:2.8 – Rollei RPX 400 @ ASA-320 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 18:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Distagon 50mm 1:4 – Rollei RPX 100 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 9:00 @ 20C

While actions on land had been limited, on the open seas, British and American ships had been chasing each other on the eastern seaboard. Back in the early months of the war, an American squadron and a British squadron had given chase but never directly engaged. On 19 August, four hundred miles off Halifax, Nova Scotia, two mainline frigates spotted each other. One ship, the U.S. Frigate Constitution, commanded by Captain Isaac Hull, mounted a battery of some 44 guns, half of which were short-range carronades. Despite being classed as a frigate, the Constitution had a heavier hull construction and could stand up and defeat most other mainline frigates while going at ships of the line. It was deadly at short range due to the carronades in her battery. The H.M. Frigate Guerrier was mainly armed with long-range cannons. It was initially built by the French and commanded by Captain James Dacres. These two ships had been part of the chase in July, but now, from the tops, the two ships identified each other and made to engage. The Guerrier fired first but at too long a range for her guns. Most shots fell short, but those that hit the hull lacked the needed power combined with the Constitution’s construction, ensuring the shots bounced off the hull. The American sailors cheerfully declared the hull was made of iron. Captain Hull, wanting to use his ship’s close-range power, added an extra sail to close the gap to within half-a-pistol shot (a distance I have not been able to get into more modern terms). The two ships pounded on each other, the Constatation’s broadsides making kindling of the Guerrier. However, the Royal Navy crew was no less active in using their guns to pound on the Constitution. After fifteen minutes of near-constant fire, the mizzen mast of the Guerrier came down, dragging the ship around, allowing Hull to fire into her bow, a raking shot. Hull ordered a repeat of the manoeuvre, but the two ships became entangled at close range. Boarding parties leapt across the narrow crossing, and the gunners of the Guerrier landed a few shots into the Constitution stern cabin briefing, lighting it on fire. The rough and rolling seas broke the two ships apart, but with the damage caused to the ship, the move broke both the main and fore masts off at the deck. Without any control and rolling dangerously, the crew of the Constitution watched as the British gunners fired again but in the opposite direction of the enemy. Taking this as a signal of surrender, Captain Hull sent a boarding party to investigate. Upon boarding the damaged ship, Captain Dacres sarcastically said that he had struck his colours with the loss of his masts. Captain Hull graciously allowed the officers to keep their swords and transferred the survivors and wounded aboard the Constitution before burning the wreck of the Guerrier. By the middle of August, the war was fully committed, and despite his best efforts to prevent it, General Prevost would be forced to start fighting. General Brock’s actions earned him the title the Saviour of Upper Canada, and when word of his actions at Detroit reached the court in London, he was made a Knight Companion in the Order of Bath. General Hull would eventually be paroled and returned to the United States, and he was found guilty and sentenced to death for his surrender of Fort Detroit at a court marshal. Still, because of his place in American history as a hero of the Revolution, President Madison would commute his sentence but strip him of all titles. The need to rebuild the Army of the North-West fell to the up-and-coming General William Henry Harrison, formerly governor of the Indiana territory, with a chip on his shoulder towards Tecumseh.

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 100 @ ASA-100 – Blazinal 1+25 6:00 @ 20C

There is a lot to still see from the early moves of the War of 1812. The ruins of Fort St. Joseph are located on St. Joseph Island in Ontario, east of Sault Ste. Marie, it’s a spot you must be purposeful about visiting. These were first investigated in 1950 and have been manned by Parks Canada since 1974; the staff there are friendly and always welcome visitors to the remote site. Mackinac Island is accessible via ferries from either Mackinac City or St Ignace; there are no cars on the island, so bring a good pair of shoes or a bike to explore. The fort is almost entirely original, including buildings from the 18th and 19th centuries. The site represents all periods in the fort’s history; even Lieutenant Hank’s sword is on display. The staff shift through different periods in the troops and civilians they portray from the 1812-era through to the American Civil War and later 19th Century. The site where Captain Roberts landed is on the island’s far side and is marked by a plaque and a period British Canon. The Amherst Navy Yard and the remains of Fort Malden (built to replace Fort Amherstburg) are both Historic sites worth visiting. However, Fort Malden does lean toward the 1830s in their portrayals. Plaques mark the site of Hull’s Landing near the Hiram Walker Distillery in Windsor, Ontario, and the François Baby House, where Hull made his headquarters, is now a local history museum in downtown Windsor, Ontario. A plaque marks the site of the River Canard skirmish on a frontage road over the Phishlago Bridge. The Duff-Baby House in the historic district of Sandwich, where Brock first met Tecumseh, also still stands and houses government offices. The former site of Fort Detroit stands at the intersection of Fort & Shelby Street in downtown Detroit. The ruins of the fort were demolished in 1827, and the 1915 bank building has a plaque on the corner outlining the site’s history. You can also see artefacts from the fort in the Wayne State University anthropology museum. There is a memorial to the Battle of Brownstown in Gibraltar, Michigan, although it is marked by Civil War Era Canons and the inscription is misleading, the memorial is located on S Gibraltar Road. The former site of Fort Dearborn can be found at the intersection of E Lower Wacker and N Michigan in Chicago, Illinois; the LondonHouse Chicago has a beautiful relief above the main entrance depicting the fort, which survived until 1858. The DuSable Bridge has a memorial to the Fort Dearborn massacre. The actual battle site is in the Battle of Fort Dearborn Park on S Calumet Ave and is marked by a plaque. The USS Constitution is now a museum ship in Boston; having survived the scrapyard twice now, she remains the oldest commissioned warship still afloat. She is commanded by a US Naval officer with the rank of Commander and 20 years of service. She is crewed by US Naval personnel and is well worth a visit. Interestingly enough, the veterans of the capture of Detroit were allowed to apply to receive the Military General Service Medal in 1847 and was one of three 1812 battles that were allowed, the other two being the battles of the Châteauguay and Chrysler’s Farm.