Lieutenant-General George Prevost, Governor-General of British North America, was displeased with his subordinate, Major-General Sir Isaac Brock. General Brock had disobeyed his orders, and instead of sticking to defence, he had gone on an offence and captured both Mackinac Island and Detroit from the Americans. President James Madison was unhappy with the results of the first months of the war, especially the surrender with little to no fight by the defenders. But what got Prevost was that Brock had received high praise for his actions and a knighthood. And with news that the Orders-In-Council were being repealed and the main complaint and the source of the war would be a non-issue, Prevost felt that an end to the conflict was near; he decided to reach out to Major-General Henry Dearborn, commanding general of the Northeast Theatre, to arrange for a series of ceasefires along the frontier. Surprisingly, General Dearborn agreed to and directed Major-General Stephen Van Rensselaer to do the same in coordination with Major-General Roger Hale Sheaffe. But Sheaffe went one step further; in addition to agreeing to the ceasefire and mutual use of the Niagara River for the movement of supplies, he restricted any movement of British troops along the Niagara frontier from Fort Erie to Fort George.

Zenza Bronica SQ-Ai – Zenzanon-PS 65mm 1:4 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 7:00 @ 20C

For General Van Rensselaer, this last term proved helpful. Stephen Van Rensselaer was not a military man; he was a wealthy business owner in New York and the leading candidate for the governorship of New York but in the Federalist party, something that many Democratic-Republicans saw as a threat to the war effort. One of the more interesting conspiracy theories in 1812 was that the Federalists were planning to secede from the Union and install a Hanoverian monarchy; of course, like most conspiracies, there was no substance to the theory. Either way, President Madison and New York Governor Daniel Tompkins arranged to keep Van Rensselaer out of the race by offering him command of the army at Lewiston and handling the invasion across the Niagara. However, all Governor Tompkins could offer was a Major-General commission in the state militia. Should Van Rensselaer decline, he would lose face with the voters, and if he accepted, he would be too busy to run; for Tompkins, it was a win either way. On 13 July, Van Rensselaer accepted the commission and set out for Lewiston. Despite being a General, having a militia commission put Van Rensselaer at odds with the Regular Army officers. It also made it difficult to work well together, and the army at Lewiston numbered less than 1,000 troops, all of whom were poorly trained and poorly supplied. But it didn’t matter because General Van Rensselaer had help from his cousin, Colonel Solomon Van Rensselaer. Colonel Van Rensselaer had combat experience, having fought at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The militia and regular army tolerated each other, each holding a mutual dislike for the other. Still, the real trouble for General Van Rensselaer came in the form of Brigadier-General Alexander Smyth. General Smyth had a chip on his shoulder for being passed over for command of the entire force in favour of a militia officer and refused to respond to summons or even orders. He arrived at Buffalo with 1,700 soldiers and camped at Black Rock. General Brock would come to Niagara on 22 August, two days after the ceasefire agreement. Even with the numbers at Niagara, Brock could have quickly taken out Van Rensselaer in Lewiston and established a solid defensive position should General Smyth move to attack, but his hands were tied. When President Madison learned of the ceasefire agreements, he immediately revoked them. He ordered General Dearborn (who, despite being a Federalist, was less inclined to fight) to proceed with the war. An order that Dearborn passed along to Van Rensselaer with the deadline of having a beachhead in Canada before winter. Van Rensselaer began to expand and train his army. Within a week, the numbers had grown to 6,000 troops by the time the ceasefire expired on 8 September. Now, on the back foot, General Brock moved fast to move his limited troops across the Niagara River. Brock would position regular troops from the 49th in Fort Erie, supported by the Lincoln and Norfolk militia, with a pair of artillery batteries near the Black Rock Ferry crossing at the Red House. A company of the 41st were stationed at Fort Chippawa. Queenston proved well defended, with an artillery battery halfway up the cliff face with the Lincoln militia and a company of the 49th stationed on the heights. There were additional militia troops and another company of the 49th in the village with a single small artillery piece. Further along the river at Vroomans Point, a heavy gun was stationed. Two companies of the York militia were at Brown’s Point, and the balance of the 41st were at Fort George. Brock could also call up the rest of the local militia, Mohawk troops and a unique all-black company of former enslaved men and free-born black citizens.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 35mm 1:3.5 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 10:00 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Plus-X Pan (PXP) – Kodak TMax (1+4) 5:45 @ 20C

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm 1:2.8G

Stationed at Sackets Harbor since the British assault several months previous, Major-General Jacob Brown suffered like other armies in the US from lack of supplies for the garrison. It proved so insufficient that Brown used his funds to purchase food and blankets for the soldiers. But the real lack was in ammunition, especially when Captain Benjamin Forsyth and a company of US riflemen arrived at Ogdensburg. Forsyth’s troops were a unique unit in the American army, armed with the Model 1803 Harper’s Ferry Rifle, which, while a muzzle-loading flintlock weapon, had a rifled barrel for long-range accurate fire. Something that both the British and Americans had begun experimenting with since the early 19th Century. General Brown suggested that Forsyth conduct raids against the British supply lines on the other side of the St. Lawrence River. The easy target was the community of Gananoque; while small, it played a vital role in the Montreal to Kingston supply route; it was also a major spot for forming convoys, had a large government warehouse and was lightly defended. Forsyth, with a company of riflemen supported by local militia troops, landed on 21 September approximately three kilometres outside the settlement, following the Kingston to Montreal road in a skirmish line advancing slowly in the growing light. Outside the town, the advancing Americans were spotted by a pair of mounted Leeds militia troopers (often called British Dragoons) who rode hard to raise the alarm. Accurate rifle fire wounded one (or both), but both were able to escape. Forsyth abandoned caution and moved his troop into the village with haste. Lieutenant Lee Sopar raised a company of the Leeds militia and positioned them along the road, blocking access to the government warehouse. When the Americans came into view, the militia managed a raged volley, which did little to deter the well-trained American troop of riflemen who closed to less than one hundred meters, delivered their volley and charged in with bayonets. The militia broke and ran across the bridge, giving the Americans the chance to run the town. Only the house of town founder Colonel John Stone was burned, and a stray bullet injured his wife. The Americans would break into the warehouse, taking ammunition, food and supplies before destroying what they could not carry. As a result, General Brock would assign his protégé, Lieutenant James Fitzgibbons, from the 49th, to oversee convoys’ defence along St. Lawrence and order the construction of blockhouses at critical points and Fort Wellington at Prescott. With winter on the horizon and General Dearborn pushing to gain a foothold in Canada, General Van Rensselaer set the invasion of Canada for 11 October. To help throw the British off, Lieutenant Jesse Elliot of the US Navy crossed the river from Black Rock to Fort Erie on the night of 9 October with a force of sailors to capture a pair of brigs, the H.M. Brig Detroit and H.M. Brig Caledonia anchored at Fort Erie. The guards aboard the ships were quickly secured and the ropes cut; everything was going to plan until the Detroit floundered in the current and dropped anchor, the alarm had been raised, and the British shore batteries opened fire. The anchor cable was cut, and the Detroit drifted further off, running aground on Deyowenoguhdoh in the Seneca language but was better known as Squaw Island (Unity Island today). A small force of British took to smaller boats crossing the river; Elliot and the crew fought back, then burned the ship to avoid capture. Upon learning this, General Brock rode to Fort Erie, fearing that the Americans would cross there with General Smyth leading the charge. This got back to General Van Rensselaer, who said that Brock had left the area to head back to Detroit to repeal a counter-invasion by General William Henry Harrison, who had taken command of the Army of the Northwest in September to retake Detroit. Seizing the chance, Van Rensselaer ordered Smyth to march to Lewiston on 10 October. General Smyth would acknowledge the order and then chose the worst possible route to bring his brigade as the fall rains had reduced most significant roads to little better than muddy tracts. The rain continued on 11 October with the troops waiting for the boats and being soaked; it also didn’t help that one of the lead pilots, Lieutenant Sims, had deserted during the night and taken all the oars with him. Realising he could only transport small numbers of troops across, Van Rensselaer called the whole thing off and rescheduled for 13 October. When Smyth learned of this and had settled back in Buffalo, he informed the General that his brigade could not be ready until 14 October.

Zenza Bronica SQ-Ai – Zenzanon-PS 65mm 1:4 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 7:00 @ 20C

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm 1:2.8G

Kyocera Contax G2 – Carl Zeiss Planar 2/45 T* – Efke KB50 @ ASA-50 – Blazinal 1+50 9:00 @ 20C

General Brock and his officers knew of the attempted crossing on the 11th. It also left them questioning where the main thrust would occur, at Fort Erie or Queenston. Hoping to get more details and to arrange for the release of the prisoners taken on 9 October, Brock sent Major Thomas Evans across under a flag of truce. Major Evans wished to speak with Colonel Van Rensselaer but was met by another man claiming to be the General private secretary and that the Colonel was ill and could not talk to him. The secretary also informed the major that any exchange of prisoners would have to occur the day after tomorrow. The repeated phrase stuck with Evans, as did the sight of some hidden boats he brought back to the other officers. Most brushed it off, but General Brock believed Evans when the major insisted that an American invasion would come on 13 October. The following day, under heavy fog and a light mist, American regulars and militia troops waited to board the boats to carry them across the river; a last-minute struggle resulted in Lieutenant-Colonel John Crystie commanding a mix of regular US Infantry troops from the 6th, 13th, and 23rd Regiments. In contrast, Colonel Van Rensselaer commanded the militia. The crossing between Lewiston and Queenston was short and easy for an experienced pilot. Still, the morning of 13 October was not ideal. Thirteen boats made up the first flotilla across the river, but only ten made it to the landing at Queenston. Two, including Colonel Crystie’s, were forced to return to Lewiston. At the same time, the third landed further up at Hamilton Cove, where a local militia unit quickly surrounded the troops. At Queenston, a sentry noticed the first Americans coming ashore and ran into the town. They alerted Captain James Dennis, who was commanding the town’s grenadier company of the 49th. The defenders were quickly and quietly roused and made ready to oppose the landing, loading the small three-pound gun with grapeshot, deadly against massed infantry. As the Americans climbed off the beach, they were met with withering fire; Colonel Van Rensselaer went down, seriously wounded, leaving command to Captain John Wool, who sent his troops ahead to scout a way off the beach without being seen by the British. With the alarm now raised in general and more Americans crossing, the Redan battery halfway up the heights opened fire, mounting an 18-pound gun and a mortar proved deadly against the crossing boats, as did the 24-pound gun at Vrooman’s point. The flurry of artillery carried to Niagara, where General Brock awoke and roused his aide, Lieutenant-Colonel John MacDonnell. Both men dressed and rode towards Queenston. Captain Wool’s scouts returned with a viable path, a narrow footpath up the heights and well out of sight from the defenders. It also allowed them to jump the crews operating the guns at the Redan battery; Wool ordered his men to climb the beach. The sun rose and burned the fog off, allowing the guns across the River at Lewiston to open fire, forcing the British defenders away from the landing and allowing more American troops to land safely. On his ride, General Brock would rally any militia along the way, calling on the York troops at Brown’s point to push on brave York volunteers (or at least according to legend). News of Brock’s arrival spurred on the defenders in Queenston. Captain Dennis sent word to Captain John Williams of the Light company of the 49th on the Heights to come down to the village. This movement caught Captain Wool off guard as the regulars marched off; it also gave them an easier job as the small force of Lincoln militia was quickly overwhelmed and surrendered the Redan battery to the Americans. Wool quickly ordered the guns spiked, driving a nail into the vent hole to prevent them from being fired. The capture of the Heights had not been expected. General Brock quickly decided to retake the heights when he arrived in the village. General Sheaffe ordered the remaining troops from Fort George and the company from Fort Chippawa to march on Queenston immediately. Organising the defenders with the soldiers from the 49th on the flanks and the militia in the centre, and himself in the lead moved up in full view of the gathered defenders. According to the stories, the line faltered only once, but a sharp rebuke from General Brock restored courage. Marching tall in his red uniform and a sash given to him by Tecumseh made General Brock an ideal target, and an American trooper would fire a round, piercing Brock’s heart; falling wordless, the general’s body was quickly carried off the field. MacDonnell raised the call to avenge the general, but he, too, was soon dead. Both Dennis and Williams were also wounded, and the survivors could not do anything but retreat in disorder. In their retreat, they chose to hide the bodies of Brock and MacDonnell in a small house across from the home of James and Laura Secord before falling back to Vrooman’s Point.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 6:00 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 6:00 @ 20C

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

By 10 am, the Americans had complete control of Queenston Heights and the village proper; Colonel Crystie and General Van Rensselaer both came across and suggested that they establish fortifications on the heights, put the Redan battery back in action and turned inland before returning Lewiston, promising more reinforcements. They also left overall command to Lieutenant-Colonel Winfield Scott of the 2nd US Artillery, with Brigadier General William Wadsworth commanding the militia. Scott would do his best to hastily erect field fortifications and restore the guns at the Redan battery to operation; the trouble is that firearms had limited range inland. While the British regrouped and the Americans busied themselves, a group of Mohawks under Teyoninhokarawen (Captain John Norton) and Ahyonwaegh (Captain John Brant) scaled the heights through another hidden path, surprising the Americans, they were unable to kill any of them and were eventually repulsed, but instead of retreating off the heights, they hid themselves in the woods. There, they took potshots and gave loud war cries, and the effect on the Americans was terrifying. The sounds even carried across the river to Lewiston. The militia quickly lost their nerve and began to refuse to participate in an invasion, as the militia was only to be used for defensive actions. Those still in Upper Canada went to the ground and deserted. General Van Rensselaer could only offer Colonel Scott boats to return to Lewiston should he wish. As the Mohawks kept the Americans pinned on the heights, the first British reinforcements arrived, the light company of the 41st under Captain Derenzy and Captain William Holdcroft of the Royal Artillery and a pair of 6-pound guns. Setting up the guns at Hamilton Cove, the British could again contest the American boats and put the American guns out of action. The British troops would retake the village by 1 pm so that General Sheaffe could arrive with the balance of the Fort George Garrison, the militia, and even Captain Rauncy’s Company of Coloured Men. Captain Richard Bullock and a company of the 41st would also arrive from Chippawa, giving Sheaffe around 800 troops, combined with the survivors of the 49th and militia troops from the initial attack. Colonel Scott’s numbers had dwindled, and he could only ask for boats to be waiting should he need to retreat. By 4 pm, Sheaffe, with the aid from the Mohawks, climbed the heights using the back route, coming out behind the American lines. The 41st Light Company and Mohawks quickly suppressed the rifle-armed troops. The main body fired a single crashing volley into the American lines before charging in with bayonets, giving war cries like their Mohawk allies. The fight was short and bloody, and the Americans clamoured down the heights in disorder. To their dismay, there were no boats; the pilots had now refused to cross. The beach turned into a killing floor as the angered Mohawks and vengeful British fired into the crowd. Two officers tried to surrender but were shot dead. It was only when Colonel Scott stepped forward waving a white cravat that the killing stopped. And to drive the point home, some five hundred militia popped out of the woods to surrender also. General Sheaffe would call a ceasefire and truce to allow American surgeons to cross and tend the wounded and return the dead. Colonel Scott, four other lieutenant colonels, regulars, and militia were taken prisoner; the militia were paroled and returned home, and the regulars and officers were marched off to Quebec City. General Van Rensselaer would resign his commission and ultimately lose the governor’s seat. Command of the invasion would pass to the now Major-General Alexander Smyth, who had sat the whole thing out in Buffalo but soon had the idea that he would succeed where Van Rensselaer had failed.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 6:00 @ 20C

Kodak Pony 135 Model C – Kodak Anaston Lens 44mm ƒ/3.5 – Efke KB 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:30 @ 20C

Nikon D750 – AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm 1:2.8G

Commodore Isaac Chauncy had a problem on Lake Ontario. That problem was HM Sloop Royal George, who wanted the flagship as a prize or on the bottom of the lake. Sailing from Sackets Harbor on 5 November aboard his flagship, US Brig Oneida, supported by four schooners. His mission was to destroy or capture Royal George, then raid British merchant traffic on the lake and even bombard the Royal Navy Dockyards at Kingston. On 9 November, the Oneida spotted the Royal George near False Duck Island on the Bay of Quinte and made to engage the British flagship. Despite being able to take Oneida in one-to-one combat, Commodore Hugh Earl could not take on five ships and made to run to the shelter of Kingston. He made for the north channel between Amherst Island and the mainland using his knowledge of the region and with the fading light. Chauncy would lose Royal George and turn along the island’s southern shore. The following day, Earle had almost made it to Kingston. At the same time, Chuancy took the chance to burn a handful of civilian vessels in Bath before heading for Kingston. Chauncy spotted Royal George in the dockyard’s outer harbour to bombard the ship. The American gunners had trouble hitting the British flagship, mainly due to Chauncy’s choice of guns and carronades aimed at close-range combat. When stray shots hit the town, Royal George sailed further, forcing the American squadron into range of the batteries at Point Henry, Fredrick, and the city. Fearing the destruction of his ships, Chauncy sailed out of range and fully intended to return the next day for the kill. But an incoming storm forced him to return to Sackets Harbor empty-handed. The same day that Chauncy bombarded Kingston, General Smyth proclaimed that he intended to plant an American flag in Upper Canada before the end of the year and called on all loyal New Yorkers to join and support the cause. Americans and the British largely ignored the proclamation due to the lateness of the year. The third prong of the American plan was the capture of Montreal. While General Henry Dearborn had taken some time to gather a force of close to 5,000 troops, which arrived in Plattsburg, New York, on 10 November, nine days later, his army arrived in Champlain, right on the border with Lower Canada (Quebec). Already, cracks were forming, and it was late in the year, with winter on the doorstep. Both regulars and militia were unhappy with the prospect of a winter campaign. Among the militia (making up 3,000 of the total number), the prospect of being used to invade did not sit well, as many thought that they were only to be used for the defence of the United States. General Dearborn would order regular troops with local indigenous allies under Colonel Zebulon Pike to scout ahead and suppress any local British and militia forces. Crossing the border on 20 November, Colonel Pike marched into Lacolle, facing only forty militia and Kahnawake troops; the British forces fell back in good order to raise the alarm with the local commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles de Salaberry, of the invasion. The Americans would destroy a small guard post and several buildings before moving further into Lower Canada. It was here that they fell under attack by a force of the Provincial Corps of Light Infantry (Canadian Voltigeurs) and Kahnawake under the command of Colonel de Salaberry; with the militia in pursuit, Pike crossed back into the United States only to face fire from a group in the woods and promptly returned the fire. The local militia had taken up positions in the woods to defend against a possible attack from Canada. The militia fired into Pike’s brigade, fearing them to be Canadians, and Pike fired back, thinking they were Kahnawake troops. Returning to General Dearborn, who had lost his heart in the matter, he decided to go to winter quarters and marched back to Albany.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Plus-X Pan (PXP) – Kodak TMax (1+4) 5:45 @ 20C

Nikon FM – AI Nikkor 24mm 1:2.8 – Fomapan 200 @ ASA-200 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 7:00 @ 20C

Graflex Anniversary Speed Graphic – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 – Kodak Tri-X Pan @ ASA-320 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 8:30 @ 20C

But for General Smyth in Buffalo, he had no intentions to go into winter quarters as he had 3,000 regulars and a plan. But his biggest threat was the Red House battery and support from Chippawa, and he planned to land two advance parties to destroy the battery and the bridge, giving a large landing zone to move in infantry and artillery. On 28 November, two groups departed from Black Rock on their missions. The trouble was that the night was moonless, making navigation difficult. The first party, assigned to destroy the Red House battery under Captain William King and infantry from the 13th and 12th regiments and Lieutenant Agnus and a party of US Navy sailors, landed near the Red House battery. Only four of the ten boats made the landing. Despite losing half their force, Captain King marched on the battery, facing fire from Lieutenant Lamont’s men of the 49th and a force of Lincoln militia; despite being outnumbered by the invaders, the British held off the American’s three attempts at charging the battery. But on the fourth attempt, the Americans closed, and the sailors proved their prowess in hand-to-hand combat, forcing the surrender. King and Angus would gather the prisoners, spike the guns and return to the boats. But in the darkness, the two groups were separated, with Angus reaching the boats first, finding only four. They assumed King had already left, took all four ships, and sailed across to Buffalo. When King returned, he found himself stranded. He sent men to commandeer local boats and sent them to Buffalo with the prisoners while waiting for pickup. The second party, under Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Boerstler, landed with 200 regulars from the 13th US Infantry near Frenchman’s Creek, intent on destroying the bridge. Seven of the eleven boats were landing, and the tools needed to destroy the bridge must be included. After quickly dispatching the detachment under Lieutenant Bartley of the 49th, he ordered a small party to destroy the bridge by any means. Boerstler would quickly push back a counterattack by a force of Norfolk militia under Captain John Bostwick but would then learn from a prisoner that the garrisons at Fort Erie and Fort Chippawa had been altered and were marching on the bridge. Cutting his losses, Boerstler would retreat, leaving the bridge party behind with only a third of the planking torn up. When a detachment from the 41st under Lieutenant McIntyre and a detachment under Major Ormsby from Fort Erie arrived at the bridge, they found it deserted but took up guard. The local commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Cecil Bisshopp, arrived at the Red House battery and quickly forced Captain King’s surrender. When Angus returned to Buffalo, General Smyth was most pleased with the result and dispatched Colonel William H. Winder to reinforce the advanced party and rescue King. As Winder’s force got nearer to the Canadian side of the river, he found the party of men Boerstler had left behind. He continued towards the Red House battery only to come under heavy fire from the British forces on the shore. Cutting his losses, Winder turned back to Buffalo. The irony was that Smyth could have effectively landed a force on the Canadian side but lacked the boats needed for both artillery and infantry. A second attempt came on 30 November but failed to leave the American side. Smyth sent his forces to Winter quarters while he headed south to visit family in Virginia.

Canon EOS A2 – Canon EF 35-105mm 1:3.5-4.5 – Kodak Portra 400 @ ASA-400 – Processing By: Silvano’s

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

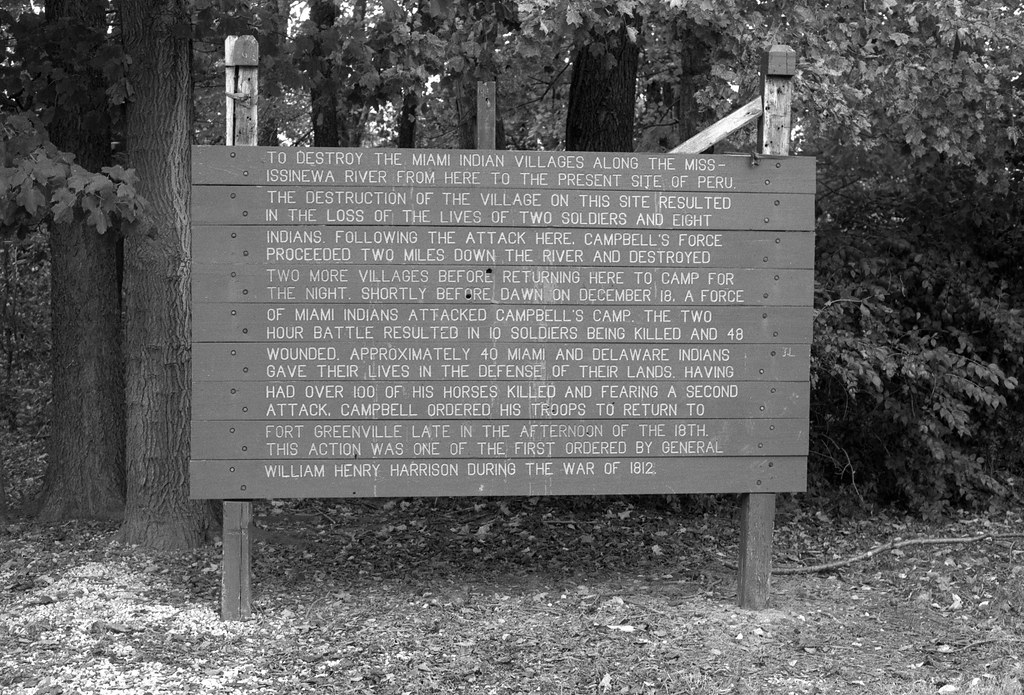

General Harrison had spent much of the fall into the winter of 1812 working towards resecuring the Northwest. Since the start of the war, the Indigenous population had taken to laying siege to the American forts and settlements throughout the region. And while they were not always successful, part of Harrison’s job was ensuring the safety and security of American citizens in the area. Harrison also began constructing a series of depot forts to provide secure locations for supply and troop movements, aiming to retake Detroit and push into Upper Canada. Harrison also authorised several punitive raids against the Indigenous population, destroying the remains of Prophetstown, a symbolic but empty gesture as the site had been abandoned since the confederation had abandoned it a year prior. Harrison authorised Lieutenant-Colonel John Campbell to take a force of 600 mounted militia and raid along the Mississinawa River, with orders to capture prisoners but only to kill when needed and not to touch the chiefs. Departing from Fort Greenville on 14 December, Campbell would conduct raids against Delaware and Miami villages, arriving at the village of Chief Silver Heel on 17 December, where they took forty-two prisoners, men, women and children. Riding further and finding nothing else, he returned to Silver Heel’s village the next day only to be ambushed by a group of Delaware and Miami soldiers who managed to kill a dozen men and secure the release of the prisoners before a cavalry charge led by Major James McDowell drove the enemy troops off and securing more prisoners. One of the prisoners informed Campbell that Tecumseh was nearby with a large body of troops; Campbell opted to return to Fort Greenville rather than test the truthfulness of the statement. The ride back was hard; by the time they returned on 28 December, half his men suffered frostbite. The action was listed as a victory as the goal of disrupting the Indigenous population had been achieved. At year’s end, all sides in the conflict went into winter quarters, the British having secured land gains in the Northwest and repelled several invasion attempts but at a significant loss. The death of General Brock would have far-reaching consequences on how the war continued in 1813 and the peace that concluded the war in 1814.

Nikon F3 – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.4 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Ilford Microphen (1+1) 10:00 @ 20C

Nikon F3 – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.4 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Ilford Microphen (1+1) 10:00 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Plus-X Pan (PXP) – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:00 @ 20C

Today, the entire length of the Niagara Parkway between Niagara-On-The-Lake and Fort Erie is spotted with historical plaques. In Niagara-On-The-Lake, Fort George was faithfully reconstructed to how it would have appeared during the war in the 1930s and features uniformed staff in both military and civilian roles. The Summer Guard portrays the 41st Regiment of Foot’s grenadier, light companies, and the regimental band. Historical markers show where Brock is said to say “Push On York Volunteers” near Brown’s Point, and the Vrooman Battery is also marked with a historic plaque. Another small marker can be found on York Road, where Sheaffe scaled. Queenston Heights is dominated by Brock’s Monument; this massive column is a memorial and tomb for General Brock and his aide, John Macdonell. The monument is operated by Niagara Parks, and you can climb to the top when it is open. You can also find memorials to Laura Secord, the Corps of Coloured Men and the Indigenous Troops, who all played significant roles during the battle. The Heights has seen war reenactments in 2012 and 2022 for the 200th and 210th Anniversaries. In both cases, dedicated reenactors have marched from Fort George to the Heights. You can also see General Brock’s coatee at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa and his new hat that arrived too late at the Niagara-On-The-Lake Museum. Across the river in Lewiston are two markers on Center Street west of North Water Street for the Battle of Queenston Heights. There is a historical marker in Gananoque on King St E to the raid on the town near Confederation Park; in the park is a plaque to Colonel John Stone, the town’s founder. A plaque to the chase of the Royal George is found in Bath, Ontario. The former King’s Navy Yards is now home to the Royal Military College of Canada. It is not open to the general public. But across the harbour at Fort Henry, you can get a good view of the college; the remains of a market battery can be found in downtown Kingston in Confederation Park across from the town hall. There is a plaque outside of Fort Erie at the Battle of Frenchman’s Creek site along the Niagara Parkway. Battery Street in Fort Erie is named such as the artillery redoubts including the Red House battery were originally located. The LaColle Mills blockhouse, initially built in 1781, is now home to a small museum in Île-aux-Noix, Quebec. A memorial to the Battle of Mississinawa can be found on N River Dr in Marion, Indiana. The actual site of the battle is also marked and is located outside of the city on Country Road 380 W and is complete with grave markers to the American soldiers killed and a memorial to the Indigenous dead. Also nearby is the Mississinawa event space that hosts an annual event that portrays what skirmishes in the Northeast were like during the War of 1812 without directly reenacting the battle itself.