Sir Francis Hincks, the proverbial third wheel in the reform movement and a figure that I knew nothing of until I started researching for this project. And while generally overshadowed by the likes of his predecessor in Robert Baldwin and his successor Sir Allan Napier MacNab as Premier of the Province of Canada his role in creating the modern province is fairly essential. The meeting of Robert Baldwin and Louis La Fontaine may have never happened if it was not for Hincks. Born the 4th of December 1807 in Cork Ireland, Francis was the youngest son of Reverend Thomas Dix Hincks. From his youth, Hincks was surrounded by the cause of reform as his father was a critic and supporter of the movement growing in England. Francis would be enrolled in school to follow in his father’s footsteps attending Trinity College before attending the Royal Belfast Education Institute. However, it soon became clear Francis had more of a head for business than academia. He soon found employment at the Belfast shipping firm John Martin & Company. He soon grew out of the firm and moved on to set up his own import/export firm, exploring opportunities in the New World. Going first to the West Indies and then to Upper Canada and the town of York through the early 1830s. He settled in the town of York in 1832 with his wife and established a firm that dealt in the import of liquor, renting space to operate from the Baldwin Family and took out advertising in the Colonial Advocate. He quickly found his social circle filled with members of the Reform Society, becoming friends with William Warren and Robert Baldwin. And while he ran in political circles, he had no desire to run for public office. But as the reform movement grew, being close to the reform movements, the Assembly (under reform control) selected Hincks as auditor to the Welland Canal Corporation in 1834.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Despite his connections, Hinck’s ventures always seemed on the verge of financial ruin. After the failure of his import business, he took on the position of general manager of the in the Farmer’s Bank. A new banking institution to counter the Family Compact controlled Bank of Upper Canada. His involvement in the new bank brought him into contact with the radical wing of the reform movement with the likes of John Rolph being heavily invested in the Farmer’s Bank. The movement towards open rebellion by the radicals worried Hincks, and he kept his distance. When even the Farmer’s Bank fell under the Compact, Hincks again jumped ship joining the People’s Bank a third institution set up by the radical reformers. Hincks made sure to keep away from the likes of MacKenzie. He never joined the rebellion that came to a head at the Battle of Montgomery’s Tavern; he still went to ground in the final weeks of 1837. While in hiding he along with other reformers cooked up the idea to seek shelter in the United States, forming the Missouri Emigration Society going to Washington DC to plead directly to the American government for land and status but not in Missouri but rather Iowa. When he learned of the arrival of John Lambton, he along with other moderate reformers saw a new hope, and he quickly left the United States abandoning the idea of moving there and returned to Canada. Hincks and Lambton spoke at length, reinforcing the concept of responsible government and non-violent revolution. To help further the cause, Hincks established a newspaper, The Examiner in June 1838 to speak on the model of responsible government and spread its word around the province.

Nikon F5 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G – Fomapan 100 @ ASA-100 – Blazinal (1+50) 9:00 @ 20C

When Upper and Lower Canada were united at the Province of Canada, Hincks at the urging of Robert Baldwin, ran for and won a seat in the new assembly for the Oxford District in 1841. During these elections, Hincks read a piece written by the radical turned moderate Louis La Fontaine. In La Fontaine’s article, an Address to the Electors of Terrebonne, he learned of the troubles faced by reformers in Canada East. He had the address translated and published it in The Examiners. He did more than just that; he reached out in a series of letters to La Fontaine pledging what support he could to fellow reformers. Then with the help of both Robert Baldwin and David Wilson, La Fontaine would come to Canada West and run in a safe district winning a seat in the Assembly. But Hincks quickly changed his tune, seeing the restrained tactics by the two leaders as taking too much time to gain their goal. Hincks shifted to supporting the colonial administration, distancing himself from the reformers to cement his new allies. Many of the reformers now viewed Hincks as an opportunist and were openly hostile towards him in the assembly and the Executive Council when Sir Charles Baggot was forced to include them. Their hostility only increased when he accepted the Inspector General posting before winning his seat back in the assembly and suggesting that some Tories be appointed to government posts. But when Metcalfe and Baldwin began to disagree, it became clear to Hincks who his allies were and joined the reformers in the mass resignation from the Executive Council. The crisis provided the catalyst needed to allow Hincks to reconcile with the Reform movement. Hincks even provided the needed encouragement to convince Baldwin, now in a deep depression to stay with the cause. To aid the cause Hincks moved to Montreal to take over as Editor of the Montreal Examiner, but when the editor in chief prevented Hincks from publishing Reform content, he simply quit and established The Montreal Pilot. And Hincks knew precisely how to target the French-Canadian public by reminding them of past actions by the Tories to undermine culture, language, and voting power. Despite his efforts to further the cause, he lost his seat in the next election. But that didn’t stop Hincks from advancing the cause, and he aimed to expand subscriptions to The Pilot into Canada West. His efforts brought him into competition with George Brown’s paper, The Globe. And while Brown had no political aspirations, Hincks still viewed him as a political rival though Brown seemed more of the radical slant. Brown would even assist and promote Hincks in his successful reelection to Oxford District in 1847. With a total reform victory, Hincks was accepted into the Executive Council and the position of Inspector General.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Kodak Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

The Reform Executive found a Province in dire financial straights, Hincks worked with Baldwin and La Fontaine to pay back the debts and built up a proper cash reserve. The arrival of responsible government and the troubles caused by the Rebellion Losses Bill sent Hincks to London to defend the bill before the Colonial Office. But when the office allowed the bill without question, Hincks remained in London to promote Canada as a place to invest. His efforts saw many British elite and businessmen pour money into the burgeoning rail industry that set to take Canada by storm. Even Hincks poured his wealth into the newly formed Grand Trunk Railroad that promised to build a rail line between Toronto and Montreal. On his return, he found the assembly in chaos as Baldwin refused to move forward on several questions. When he learned that even George Brown had attacked Baldwin and saw his anti-Catholic and anti-French-Canadian views as against the unity formed by the Reform Movement, he refused to lend his support. In the following election, Brown lost his bid to William Lyon MacKenzie, and even Baldwin failed to be reelected. Hincks sat secure in Oxford and would be appointed at Premiere as Baldwin’s chosen successor, forming the government with Augustus Morian in 1851. But even Brown didn’t stay out of the Assembly for long, winning a by-election. Rather than join the mainline reformers, Brown chose to ally himself with the radical Clear Grits due to his being stubbed my Hincks. The Hinck-Morian government held on by a thread and soon needed to seek an alliance. The interference of MacKenzie the Grits refused, which allowed Sir Allan MacNab to move in offering his support. But the cost was the formation of a new party, the Liberal-Conservatives. Under the new party, the province flourished, the railroad expanded, the clergy reserve abolished, the responsible government expanded to the municipal governments, and Hincks’ crowning achievement, the establishment of the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States, the first free-trade agreement between Canada and the United States. Of course, his high did not last long, and everything came crashing down when MacKenzie discovered profits from the sale of railroad stocks between Hincks and the mayor of Toronto went unreported. Hincks resigned in scandal, giving the premiership to MacNab. The new government would find Hincks not guilty in 1855, giving him the go-to to accept the position of Lieutenant-Governor of Barbados. In his role, he proved an effective governor in modernising the province, and he would be appointed to the governorship of British Guiana in 1861. Here he proved far less a reformer, refusing to allow responsible government in the province, and he would not be given another governorship in 1869. Instead, he was appointed a Knight Commander in the Order of St. Michael and St. George. Sir Francis returned to Canada in 1869, accepting the post of Minister of Finance in Sir John A. MacDonald’s cabinet, serving as a Member of Parliament for Renfrew North. In his role, he successfully established the modern and standardisation of the banking system in Canada. With age catching up, he resigned from the government in 1873, his last service to the government saw him head up the Manitoba/Ontario border commission. But he was far from done, taking on the post of President of the Consolidated Bank of Canada in 1875. Hincks; age did not act in his favour, and when the bank collapsed through his negligence, he faced criminal charges under the banking laws, he help write and champion in Parliament. In 1879 he was found guilty of willfully submitting false statements and deceptive returned, and though acquitted of all charged he was removed from his post and finally retired. Moving to Montreal, he began his work on his memoirs, but his life ended on the 18th of August 1885 from smallpox.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

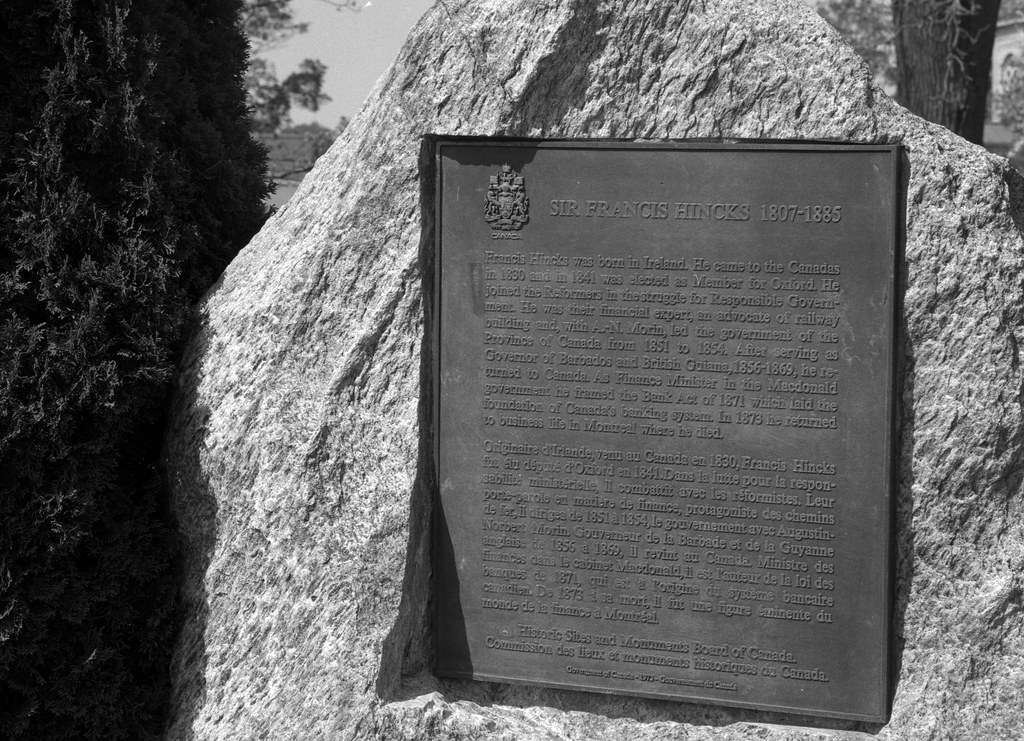

Today there is little to remember Hincks, although his legacy as a robust financial administrator and the highly regulated banking system serves still today and many of the laws that he helped to create remain in place today. The railroad he helped finance, The Grand Trunk would be the sole survivor of the colonial railroads lasting until 1923 when it was absorbed into Canadian National Railroad. A plaque to Sir Francis Hincks can be found outside the Oxford County Courthouse in Woodstock, Ontario the district he represented until his resignation as Premier in 1854. The Hincks Township in Quebec would be named for Sir Francis, but in 1975 changed to Lac-Sainte-Marie. In Bridgetown, Barbados there is a Hincks Street for his time as Lieutenant-Governor of the island nation.