Many have heard the analogy of an elephant and a beaver to describe the relationship between Canada and the United States. Even though we are two separate countries and cultures, whatever happens in the United States is like when the elephant rolls over, it does and will affect Canada. The American Civil War is the perfect example of what happens when the elephant rolls over. While the conflict was primarily an American war, it had ripple effects across the globe. The war is not the primary focus of this project, however, as I mentioned in the previous post, is one of the external reasons to drive British North America towards Confederation, and even affected the discussions surrounding confederation. All mainline historians agree that the primary cause of the American Civil War was a battle on State’s rights, specifically the right to keep humans of colour as property as slave labour. The history of slavery in North America is a long and complex one and deserves a great deal of attention. And while America itself had been divided on slavery, the fact was that it remained a legal across the entire United States and in the American Consitution and through Federal Law such as the Fugitive Slave Act. That being said, several states had banned the practice of slavery, while others embraced it. The division along the Mason Dixon line was clear, and a compromise between adding free and slave states had been struck. But not everyone was happy. While the free states maintained their economy through industrial growth, the south remained dependent on agriculture. And those farms and plantations relied on labour filled by men and women of colour who were treated not as human, but property. There was a healthy abolitionist movement in the United States, and while victories had been made elsewhere in the world, those of colour did not find equal footing even in Canada. A network of those abolitionists aided in guiding those seeking freedom out of their home and into the Free States and even Canada. And though many pro-slavery leaders were in positions of power, many states were feeling the pinch and began to discuss leaving the union openly. The problem was that there were processes in place to add states to the Union; there were none to allow them to leave. It all came to a head with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the Office fo the President. Lincoln, a known abolitionist, did not sit well with the pro-slavery governments in the slave-owning states. Several states issued writs of succession, all of which the Federal Government ignored. And in February 1861 delegates of seven states, South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Floridan, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas met in Montgomery, Alabama. The chief purpose of the conference was to establish a newly independent nation, the Confederate States of America. Their constitution would enshrine the right to own humans, specifically blacks, as slaves and property, and allow states to both join and leave should they desire. Jefferson Davis was appointed President and the capital set in Montgomery. That said the Federal government nor any other nation recognised the Confederacy. And it wasn’t for lack of trying, Davis sent envoys to Washington to see about purchasing Federal Land in the new Confederate States, a request firmly ignored by Washington. To prove their point, Lincoln ordered all army posts to stand ready to defend any attempts to seize their posts. Little did Major Anderson know, that his post, Fort Sumter would be the first. On the 12th of April 1861, Confederate forces began an artillery bombardment. After two days of shelling, Anderson received permission to surrender his post. American was a nation divided; the Civil War had begun.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford HP5+ @ ASA-200 – Pyrocat-HD (1+1+100) 9:00 @ 20C

Despite having to fight a war, Jefferson Davis would be desperate to seek foreign diplomatic relations. He hoped that such recognitions could gain allies and see the Confederacy survive separate from the United States. And while he continued to receive the cold-shoulder from Washington, he turned to the major powers in the old world. Special commissions were sent across the Atlantic to both France and England to see if either would be willing to recognise them. To England the special commission, headed up by William Yancy. Yancy had been an early succession supporter and a friend and ally to President Davis. Word of Yancy’s arrival and reception in England reached Washington and the secretary of State, William Deward issued a dire warning, first to the British ambassador, Richard Lyon and the British Foreign Secretary, Sir John Russel. The warning stated that any formal recognition of the Confederacy would lead to war. Russell took the warning seriously, and at the advice of both Lyon and the American ambassador, Charles Adams met with Yancy in an informal setting outside his official office. Russell’s most significant concern would be the reopening of the Atlantic Slave Trade. The Royal Navy’s African Squadron had since 1803 had been tasked with and managed to stamp out the horrible practice of trading humans for money and goods. The last illegal slave ship had landed in 1858, moving those men and women aboard into the local trade. Yancy assured Russell that the Confederacy had no such plans, how true that statement was unknown, but Russell took the envoy at his word. Yancy hoped that his continued informal meetings were leading to something formal, but Russell had no intentions to do so, England could not afford another war in North America. Many in the British government felt that the only real solution to the American Civil War would be a partitioned country and thought that England would act as a neutral mediator. Queen Victoria would take Russell’s advice to declare England neutral in the whole matter, stating clearly that the Civil War was an internal American matter. The declaration did not sit well with either the American or Confederate Governments, as a neutral nation, both sides could make use of British controlled ports. However, there were strict rules, only non-military supplies would be sold, and ships could exclusively remain in port for twenty-four hours. But Yancy did not give up hope. He continued to meet with Russell, hoping that he could persuade the British for some formal relations and showed the early Confederate successes to show that they would be victorious. Plus he explained that any ties with the Confederacy would have valuable trade that would benefit both. Russell was more concerned with protecting British interests. Most concerning was the use of Privateers by both sides, Russell feared that they could attack British merchant ships. Both Russell and Lyon rushed to get the United States to sign onto the Paris Accords that reduced the use of Privateers by nations at war. But many saw and were more than happy to say that the continued meeting was a good sign and that it was leading to a formal meeting. It was, of course, a complete falsehood, however many Confederates were buoyed by the lie and began to send letters of support and propaganda to the British missions in the major Confederate cities, all of which were forwarded by diplomatic pouch to Lyons. The Americans quickly caught on, having a network of spies in the Confederacy. Seward was furious when he learned of the movement of Confederate propaganda, and while the British weren’t too pleased with the fact the Americans had opened a diplomatic pouch, Russell was clear to his actual reasons. When Yancy next tried to arrange a meeting, Russell’s opinion had chilled, and a brief note responded that all future communication was done in writing. Yancy, fearing he failed, tendered his resignation to President Davis.

Sony a6000 + Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

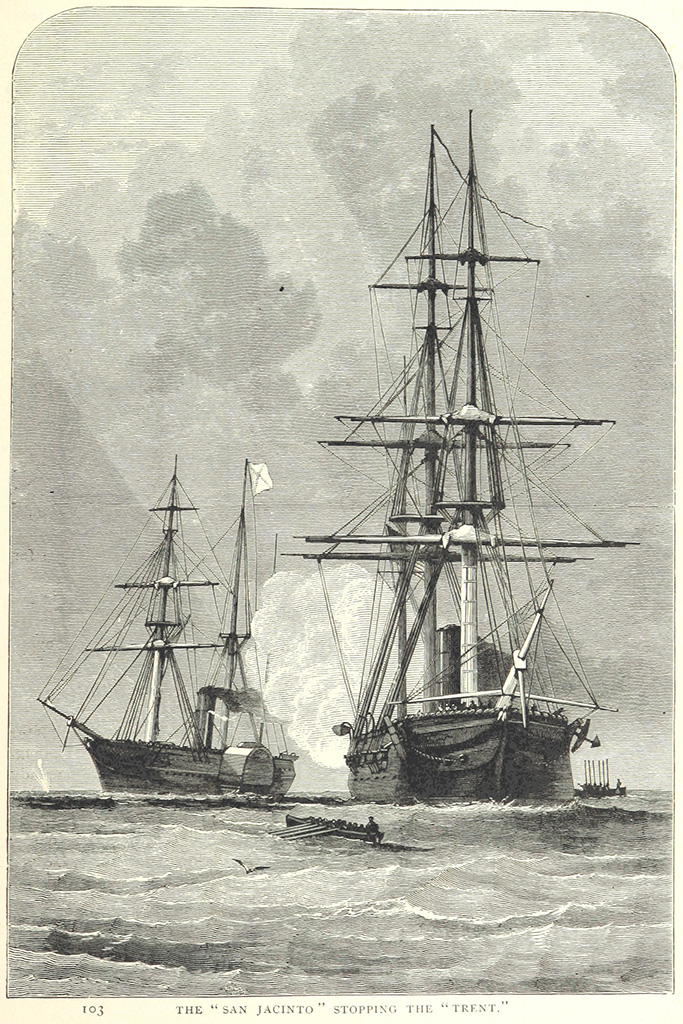

President Davis took a different stance, feeling that only direct action would shake England and possibly other nations into action he promptly appointed two official diplomats and charged them with visiting and taking up office in London. The men, James Mason and John Slidell, were hoping to depart for England from Charleston Harbour. The only trouble was that the US Navy had, since the start of the war, made a point to blockade every Confederate port. In response, the Confederate Navy opted to use fast ships called blockade runners. But when the Americans learned of the planned departure, because the Confederacy decided to announce this move publicly, increased the number of ships blockading Charleston. The plan to use the fast and capable CSS Nashville (2) would no longer work. The ship had no hope in running the strengthened blockade and was too big to navigate the side channels to outflank the American warships. An overland trip to the Gulf of Mexico was also out of the question. Help came in the form of the offer to purchase a small cargo steamer that would be both fast and could get out the backdoor. The Confederates did not have the funds to purchase the ship outright, but a plantation owner offered to purchase the ship and have the ambassadors onboard as honoured guests. The steamer, now rechristened Theodora. Their goal was Nassau in the Bahamas where they planned to catch passage on a Royal Mail Steamer to England. The Americans were furious when they learned the diplomats slipped through their nets, but they assumed that it was aboard the Nashville. The USS James Adgar (9) to sail to intercept the Nashville while on route to England. When the Theodora reached the Bahamas, only to learn that in their delay the last mail steamer had already departed, but that a second ship, the RMS Trent was still due in Havanah in Cuba. Nearly out of fuel, the diplomats landed on Cuba on the 15th of October 1861, ironically the same day that the James Adgar reached South Hampton. The Royal Navy officials confirmed that the Nashville had not been in port. The captain most impressed that they had outrun the Confederate blockade runner, filled the Royal Navy in on their plan. While they were not concerned about the actions of the American warship they only requested that any capture take place in international waters, to prove their resolve, they established a blockade to keep any American or Confederate ships outside the national limit. On the 7th of November, Mason and Slidell boarded the Trent to begin their journey to England. Little did they know that word of their departure would again be crowed about through Confederate papers, one such paper reaching the desk of Captain Charles Wilkes. Captain Wilkes already had a reputation in the Caribbean. He was disliked by both the British for often violating neutrality and by the Confederates by his flaunting and bending of rules to suit his needs. Wilkes knew he could intercept the Trent and positioned his warship, USS San Jacinto (6), on the route the mail steamer. The Trent a day out of Cuba was heading into a trap; the watchman shouted out a sail on the horizon as the American warship came into view, Captain James Moir ordered the colours raised hoping that the Americans would respect their neutrality. Instead, Wilkes ordered a shot across the bow, Moir ordered full steam ahead as a second shot screamed across even closer. Not wishing to lose his ship, Moir ordered full stop. Wilkes gathered a party of Marines and Sailors commanded by his second Lieutenant Fairfax to go over, board the Trent seize the contraband (those being the diplomats, staff, luggage, and families) and return. Wilkes then added another order, should the British fail to comply the ship was to be taken as a prize. Fairfax, however, had a much different view of Wilkes, he had no intention of taking the Trent as a prize as such an act could and would lead to the British declaring war. When the two cutters arrived at the British mail steamer, Fairfax went aboard alone demanding to see the captain. Maintaining his bold front, Fairfax demanded permission to search the ship and detain the Confederate diplomats. Moir refused, and when the crew made threats at the American Lieutenant, the Marines and Sailors rushed aboard. It seemed renewed violence between the British and the Americans were about to start, not wanting trouble, the two diplomats stepped forward identifying themselves. Then in a twist registered a formal complaint to Captain Moir and surrendered to Fairfax. A second ask for a search was again rebuffed, and rather than start a war, Fairfax returned with his prisoners.

Edward Sylvester Ellis [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Wilkes sailed into Boston Harbor, a hero. The bold capture of the diplomats had made the captain an instant media sensation. There was even talk of a congressional gold medal. Lawyers, politicians, and civilians alike spoke at great lengths on the capture often defending the captain. While there were a few, who felt the capture was illegal. And for now it seemed Wilkes and the US Government got away with it, at least until the Trent arrived in England and the government took offence at the illegal actions of the American captain. In a telegram to Washington, the British made harsh demands, calling out the Americans as hypocritical for their response to the 1807 attack and boarding of the USS Chesapeake a neutral American ship by the HMS Leopard, which nearly turned the War of 1812 into the War of 1807. But a technical glitch prevented the telegram from reaching Washington. Instead, the discussions around the Trent Affair fell in the laps of William Seward and Richard Lyon. The two proved able diplomats and negotiated in good faith, but neither was going to get what they wanted. That didn’t prevent the two armies and navies from preparing for war. The Royal Navy deployed ships to Halifax and British Columbia, troops were moved across the Atlantic and garrisoned across British North America. The Canadian government increased the size of their Militia, and larger Battalion sized units were made up from smaller units seeing the formation of the 1st and 2nd Battalion Volunteer Militia Rifles of Canada (better known today as the Queen’s Own Rifles) in Montreal and Toronto, Hamilton saw the formation of the XIIIth Battalion Volunteer Militia of Canada (Infantry). Smaller forces were raised to defend the Welland Canal in the form of the Dunsville Naval Brigade and the Welland Battery. The Americans were no slouches either, building improvements at Fort Niagara and stationing armed warships on the Great Lakes. But the threat of a second war did not sit well with the American public, and soon public opinion turned against Wilkes. While the American government stopped short of a formal apology, Lincoln did make a statement to indicate that Wilkes had acted alone and without orders. And on a cold December night, the diplomats were released to the Royal Navy and boarded the HMS Rinaldo (17) in Boston and international waters transferred to the RMS La Planta and sailed for England. By the time the initial telegram reached Washington, the matter had been resolved, and the Confederacy never knew how close their actions came to inciting a northern War although that would have helped their plans.

Intrepid 4×5 – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 – Kodak Plus-X @ ASA-125 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 7:30 @ 20C

The Trent Affair only served to drive England further into neutrality, and officially they did and said nothing about the Civil War. Gone were any offers of negotiation between the Confederate and American governments. Officially, any British subject was barred from supporting either the Americans or Confederates in the conflict, but that did little to stop many private businesses and citizens from showing their support, of both sides. Many Canadians would cross the border and fight for both the American and Confederate Armies. American Army recruiters would cross into Canada visiting the Buxton, Dawn, and the settlements in the former Queen’s Bush, men who had escaped slavery signed up and headed south to fight for the freedom of their nation. The migration only increased after the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. Despite efforts by the Canadian Government to protect the border, Confederate agents would often slip into Canada and conduct terrorist acts against the United States from the North. Canadian Premiere, John A. MacDonald would form two special police forces, the Western Frontier Constabulary and the Montreal Water Police to both patrols the Canadian/American border and to spy on the Confederates. British arms would be sold to the Confederates and warships and raiders were built by private shipbuilding firms in England. The most infamous of all these British built Confederate raiders was the CSS Alabama. While many believed the Alabama was both built and armed in the yards of John Laird & Sons & Co, it was more likely armed in neutral territory when the Confederate navy took possession. Construction had been arranged to Fraser Trenholm Company a cotton firm with ties to Confederate cotton interests, who also arranged for British guns to be loaded on to her in the Azores. The Alabama proved an effective raider in the Confederate Navy she would sink in 1864 during an engagement with the USS Kearsarge (7) off the coast of France. English shipyard would eventually build four other raiders for the Confederate Navy, the CSS Florida, CSS Shenandoah, CSS Lark, and CSS Tallahassee. Ultimately early successes for the Confederacy would not be enough to force an end to war, and on the 9th of April 1865, the Confederate army would surrender at the Battle of the Appomattox Courthouse.

Rear Admiral J. W. Schmidt [1] [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

And while the war ended the effects of the war carried on, the Americans would attempt to punish England by revoking the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 with Canada and increasing tariffs on British made goods. The American government would attempt to get money out of the British Empire for the damages caused by the Alabama. Senator Charles Sumner wanted to bill England for two billion dollars for damages caused by the Alabama and other British built Confederate Raiders. The Americans were more than happy to accept all British holdings in North American instead of the cash. The Civil War, combined with the ongoing troubles with the Fenian Brotherhood, had left a strong Anti-American sentiment in Canada, and they had no desire to be annexed. The Alabama Claims would not be settled until 1871 when the Treaty of Washington was signed, beginning the special relationship between England and the United States. England would still pay for the claims, a sum of 15.5 million. And while the war has been over for over a hundred and fifty years, the effects of that conflict are still felt to this day. Despite the Emancipation Proclamation, men and women of colour still suffered discrimination today, the Jim Crow Laws and the revitalisation of the Ku Klux Klan in the early 20th Century and the raising of monuments to Confederate leaders during those times to remind those of colour of their place. And while the Civil Rights Movement achieved further victories, people of colour still suffer discrimination, systemic racism, and degradation of their rights to this day. And while it’s easy to dismiss this as a purely American problem, we in Canada are not innocent. We do struggle with systemic racism both in our past and in our present. You can visit many American civil war battlefields today, I’ve had the honour to visit Gettysburg twice now, you can also find a memorial to those in Canada who went and fought in the Civil War in Cornwall, Ontario. The wreak of the Alabama can be found at 49°45′9″N 1°41′42″W off the coast of France where she sank.