The Welland Canal attracted a wide range of industry. But most of the industry used the Canal as a way to bring in power to drive the machines, transport in raw materials, and ship out finished products. But if there is a single industry that not only depended on the presence of the Canal but also provided goods and service to the Canal, it is the shipbuilding industry. Shipbuilding in Canada was nothing new; ships were the cars of the day as water was the highway. And with most the communities that existed in Canada were on the water. While Mills drove inland communities on rivers communities on lakes gathered around shipyards. The Royal Navy had operated shipyards along the Great Lakes from the days of the American Revolution, and these same yards built the massive warships that fought for dominance of the Great Lakes during the Anglo-American War of 1812. But in the post-war, most ships were small civilian vessels designs to carry cargo rather than cannons. The Welland Canal required not only ships, known as canallers but also facilities to repair ships transiting the Canal. And like the mills, shipyards would become another anchor industry for the Canal and her communities.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

The first shipyards appeared on the Welland Canal in what is now downtown St. Catharines. Formed in 1828 north of where the Burgoyne Bridge is today. By 1836 the yard came under the ownership of Louis Shickluna. The second shipyard in St. Catharines stood near the modern intersection of Oakdale and Winchester. These two yards were small, dedicated to building barges and other ships dedicated to service on the Canal. The 1830s saw increased traffic on the great lakes, and port communities on the Canal provided the best location for shipyards, and the idea was not lost on men like Robert Abbey and Alexander Muir. Both men would set up shop in Port Dalhousie, taking advantage of the movement of the Canal’s entrance further inland with the completion of the Second Canal. Robert’s yard would come first in around the 1840s he also brought his two sons John and James, to work with him. Muir, who had made a name and a captaincy for himself on the Great Lakes arrived in 1850. Muir would convince his brothers to join in the business and set up a floating drydock. The Muir brothers weren’t just interested in building ships for the Canal they wanted to build larger vessels that could travel lakes and even oceans. So they also purchased timber, sawmills, and cordage facilities. That same year, John and James opened their shipyard at Port Robinson. The Muir brothers launched their first ship in 1855, a schooner named Ayr after their hometown in Scotland. By far, the Muir Brothers proved to be the most successful shipyard on the Canal, adding a permanent drydock in 1866. But they weren’t too picky on their clients, one of the ships they built became a slave ship in the American slave trade. And Alexander maintained his role as a Captain, a stickler for the rules even chased his employees off the job site when they were working on Sunday. Sabbath Laws in Canada are a whole other ball of wax. But the Muir brothers remained dedicated to the construction of sailing vessels. The Abbey Brothers in Port Robinson would join the slow march forward and started building steamships almost from the start, often employing factories on the Canal to create both engines and boilers. But with the arrival of the Third Canal, which bypassed the lock onto the Chippawa River, the Port Robinson Yards were no longer viable. The final ship, a steamship the City of St. Catharines was launched in 1874 and two years later the yards closed. And by 1890 even the Muir Brothers ceased shipbuilding but continued to repair ships. In fact, by the end of the 19th Century, most shipyards on the Welland Canal were reduced to repair work only.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 70-210mm 1:4 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 28mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Alexander Muir would work at his shipyards until he died in 1910. Beaty and Sons opened their shipyard in 1917 modifying several older piers into drydocks. They had won a government contract to build five ships to aid in the construction of the new Canal. But the yards were short-lived and closed in 1920 after the five ships were completed. After the Fourth Canal opened in 1935, the Muir Brothers docks continued to serve as a small repair yard in Port Dalhousie even though canal traffic was now mainly large cargo ships and transited the Canal from Port Weller. Recognising the need to have a small dockyard, the Federal Government opened the Port Weller docks in 1947. The docks provided minor repairs but were primarily storage for support craft and spare parts. The Muir family closed down their Port Dalhousie yard in 1953 selling everything to the Port Weller Docks. But the sale of Port Weller in 1956 to Upper Lakes Shipping Co returned the construction of new ships on the Welland Canal. Throughout their operation, Upper Lakes built forty-two ships. Icebreakers, Bulk Carriers, Tankers, Scows, and more would splash down into the Welland Canal. And by the 1990s, Port Weller was the only shipyard actively building ships on the Great Lakes. But all was not well, and the economic downturn in the 2000s saw the Port Weller Docks pass through several firms before shutting down. The hit, combined with a general decline in the industry was felt across the entire canal community. Algoma Central opened their small repair yard at Port Colborne, and Marine Recycling opened a ship-breaking yard also. Not wanting to lose out on a repair yard, the St. Lawerence Seaway Corporation bought up the shuttered Port Weller Docks and turned to Heddle Marine to operate a repair yard there in 2015. And now, Heddle Marine is even looking to build ships again at Port Weller to supply new icebreakers to the Canadian Coast Guard.

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 70-210mm 1:4 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

Minolta Maxxum 9 – Minolta Maxxum AF 70-210mm 1:4 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

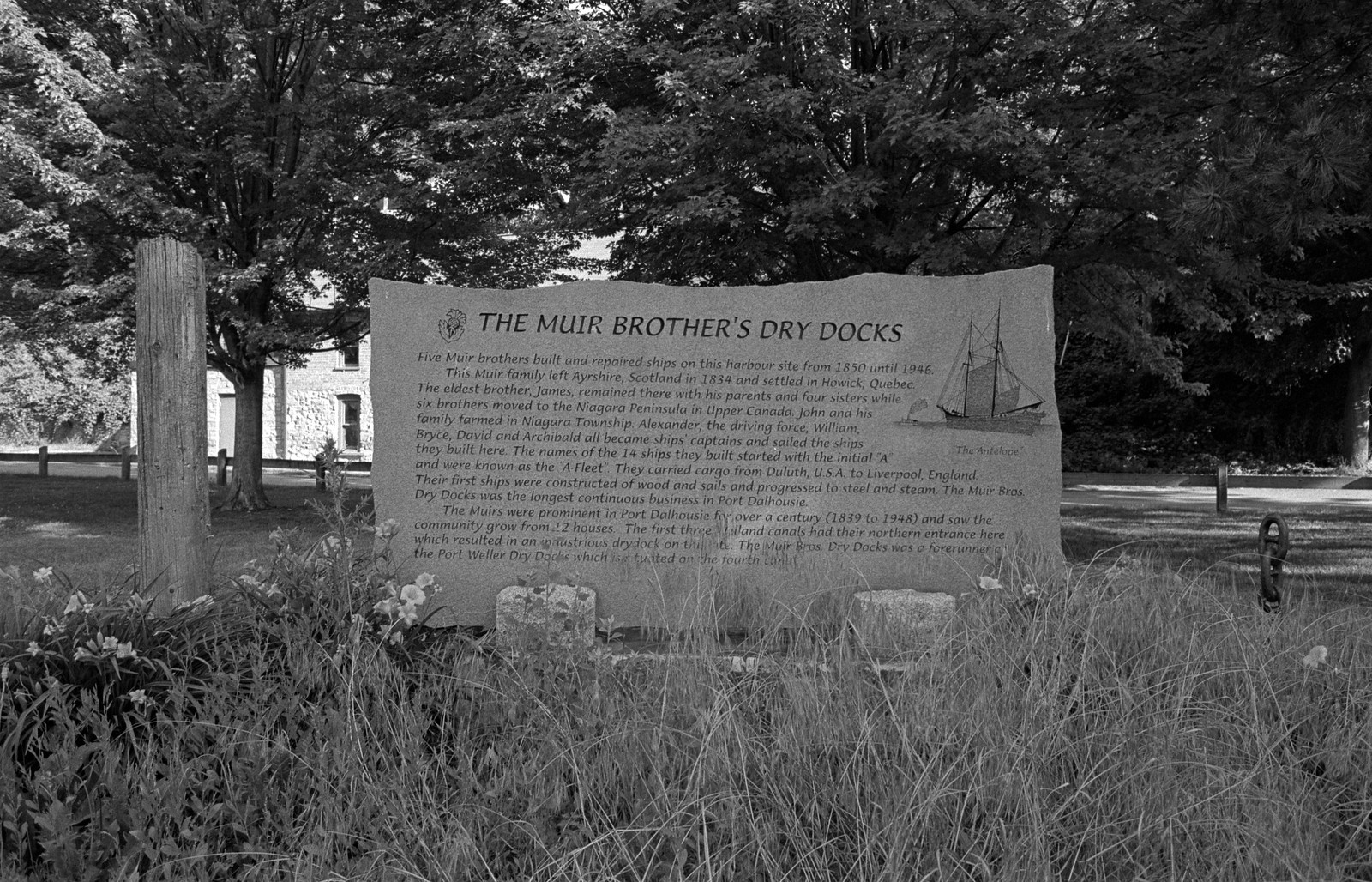

Today you can still find plenty of reminders of the shipbuilding legacy of the Welland Canal. In Port Dalhousie, Rennie Park is the former site of the Muir Brothers drydock; a stone marker outlines the history of the site. And the original 1850 office and store stands still as Dalhousie House. Although the building is tucked away and you need to look carefully. In St. Catharines, the Shickluna yard was abandoned in 1891 and saw some commercial use until 1901. Today most of the yard is buried under Highway 406 although a historical plaque is located nearby and some archaeological work has been done. The Simpson Yard at Winchester and Oakdale is completely paved over with little left to tell you what used to be there. The Port Weller Docks remain a common sight near Lock 1 of the Fourth Canal. And one ship built by the Upper Lakes Co remains in service the CCGS De Groselliers an icebreaker. There is also nothing left of the Abbey Yard in Port Robinson, it’s buried under the Port Robinson Park next to the old Second Canal lock. In Port Colborne the yards of Algoma Central and Marine Recycling are off-limits, you can see them out in the distance from the island that sits between the historical and current canals. In a final note, I’m happy to announce that the book on this project is now available for sale and would make a perfect Christmas gift for those who live in the Canal Zone or just have an interest in the Canal itself. You can pick it up over on Blurb, books start at 63.03$ CAD.

Written With Files From

Jackson, John N. The Welland Canals and Their Communities: Engineering, Industrial, and Urban Transformation. University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Colossal Project: Building the Welland Ship Canal, 1913-1932. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

Styran, Roberta M., and Robert R. Taylor. This Great National Object: Building the Nineteenth-Century Welland Canals. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

Styran, Roberta McAfee, and Robert R. Taylor. Mr. Merritt’s Ditch: a Welland Canals Album. Boston Mills Press, 1992.

Jackson, John N., and Fred A. Addis. The Welland Canals: a Comprehensive Guide. Welland Canal Foundation, 1982.

Styran, Roberta M, et al. The Welland Canals: the Growth of Mr. Merritt’s Ditch. Boston Mills Press, 1988.