While the major campaigns of the War of 1812 get the spotlight and widely known, and it is true; these were the battles that shaped the course and action of the war those weren’t the be all and ended all of the war. And even today the British capture and occupation of what is now Maine, or as it was two hundred years prior Massachusetts, the War of 1812 remains relatively unknown even to those living in the modern communities today. I would not have even known about this conflict if it were not for my reading and participating in the reenactment of the war as the unit that I am a member of, the 7th Batallion, 60th (Royal American) Regiment of Foot fought in what is known as the Sherbrooke Expedition.

My rather well worn 60th Golf Shirt near the Fort George Marker in Castine, ME

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

For the eastern seaboard, the first two years of the war were taken up mostly by the naval battles between the US and Royal Navies. The governor of Nova Scotia, General Sir John Sherbrooke could do little more than muster the local militia, mount guns along the shores, and pray that the might of the Royal Navy would prevent any American invasion. And while Sherbrooke could not invade, he did see an opportunity. The war was not well received in the New England States, and rather than antagonize his neighbors, Sherbrooke opened up trade relations. Sherbrooke began to issue passports and licenses to American merchants allowing them to trade with the British Colonies in the Maritimes; the move boosted the economy of Nova Scotia. The unofficial peace the two sides enjoyed was not to last. With the abdication of Napoleon following his defeat at The Battle of Leipzig, the might of the British army was about to come crashing down on the United States. The British Parliment and Sir Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington wanted the American war to come to a quick end.

The Halifax Defenses ensured that no American captain in their right mind would attack the center of Royal Navy Activity in North America.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Portra 400 @ ASA-800 – Processing By: Burlington Camera

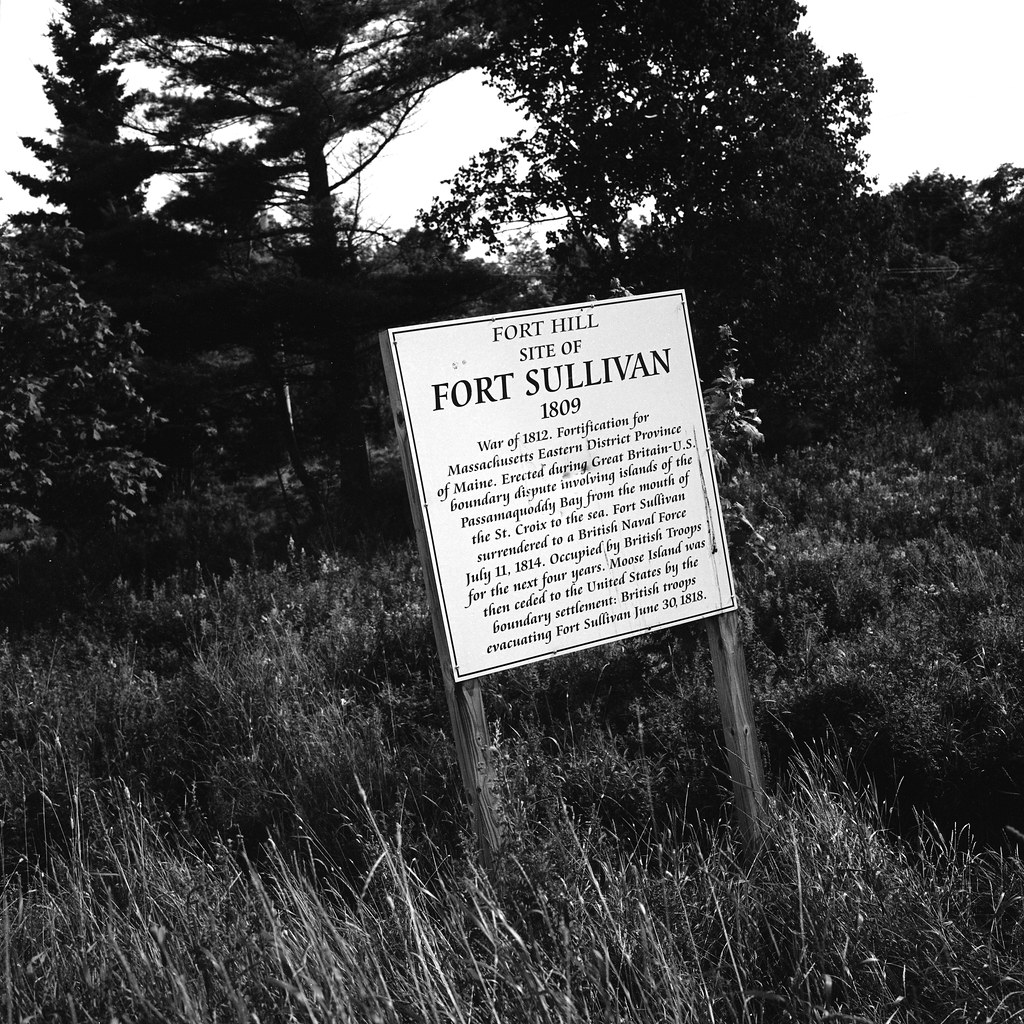

Governor General Sir George Prevost ordered that Sherbrooke establish a land link between Halifax and Quebec City. The idea of capturing the eastern part of Massachusetts had been in flux since the Treaty of Paris (1783). So to Sherbrooke, the reoccupation of the territory seemed the best option. His first move was to send Commodore Sir Thomas Hardy and Lieutenant Andrew Pilkington with a thousand regulars to capture Moose Island. Upon seeing the British fleet, Major Perley Putnam surrendered his garrison of eighty-five regulars of the 40th US Infantry along with Fort Sullivan and the village of Eastport. Hardy and Pilkington immediately renamed the post, Fort Sherbrooke and as the island was considered by the Crown as British ordered that all citizens declare an oath of allegiance to the British Crown. A majority of the citizens did, those who refused were ordered to leave. To maintain the island and deter any counter attack a garrison of 800 regulars were left behind.

Fort Sullivan surrendered quickly without firing a shot. Today there are a few remains including the hill, a cannon, and the 1808 barracks in Eastport, ME

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

But Moose Island was a small spit of land, to secure a land route between Halifax and Quebec City the British would need to reestablish an old colony. In 1779, Brigader General Francis McLean established the colony of New Ireland; Sherbrooke was going to take a page out of the history book. Five ships, HM Ship Dragon (74), HM Frigate Endymion (40), HM Frigate Bacchante (38), and HM Sloop Sylph (18) were placed under command of Rear Admiral Richard Colpoys while ten transports carried 3,000 regulars from the 29th (Worcestershire), 60th (Royal American), 62nd (Wiltshire), and 98th regiments under Major General Gerard Gosselin set out from Halifax late in August 1814. By the 30th the invasion fleet was joined by the HM Sloop Rifleman (18) which brought news that Captain Charles Morris and his ship, the US Brig Adams (20) had taken shelter at Hampden. The Rifleman would join the invasion fleet along with HM Ship Bulwark (74), HM Brig Peruvian (18) and HM Frigate Tenedos (38). Sherbrooke decided to prevent the Adams from escaping first before capturing or destroying her. The fleet sailed north on the Penobscot River for the small village of Castine. On the 1st of September, Lieutenant Lewis, commander of the garrison at Fort Madison that watched over the village of Castine received word from the British fleet requesting his surrender. Having only 40 men under his command, Lewis chose to fire several volleys at the invaders from the fort’s four 24-pounders then spike them. Lewis, his forty men, and a pair of smaller field guns left without a fight. Landing a small force of regulars the village of Castine quietly came under British occupation. Sherbrooke would order that Fort George, built by General Francis McLean be rebuilt and reoccupied. Additional fortifications were constructed around the town such as Fort Castine (built on the remains of Fort Madison).

Fort Madison as it stands today. The 24-Pound Cannon dates to the War of 1812, however the earthworks are from the Civil War.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

With the river blockaded Sherbrooke would assign the capture or destruction of the Adams to Captain Robert Barrie of the Dragon, Barrie would take a ground force of 750 regulars, along with the Dragon, Slyph, and Purivan. For Captain Morris, the situation was not good. His ship was still under repair, and he only had a crew of 150 sailors and Marines. General John Blake, the local militia commander, offered a force of 600 men. The timely arrival of Lieutenant Lewis gave Morris an extra pair of field guns and forty regulars. Calling the townspeople together, Morris said that he would stand and defend the town providing the militia held. If they did not, Morris would destroy his ship and retreat. The trouble was that the militia had never seen combat, and while Blake had confidence in the men, Morris had little.

If the water level is low enough, you can still see the remains of the Crosby Warf. Just ask permission as it sits on private property today.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Moving the guns from his ship, he set up a battery along the shoreline and the Crosby Warf. His sailors would form the right flank, while Lewis his men and two field guns would make up the right flank, the center would be Blake’s Militia. They only thing that they had to their advantage was that they had the high ground. Sherbrooke hoped to protect the peace, and in a proclamation informed the local population that should they wish to trade with British North America, they would need to swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown. It was not required as it had been on Moose Island (the British felt Moose Island was rightfully theirs). Any other would simply have to swear an oath to keep the peace and turn in their weapons. Sherbrooke ensured that the garrison would pay fair prices for all the goods and services they required.

Bald Head Cove as it is today. Probably hasn’t changed much in 200 years, but with the dry summer the water level was pretty low.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

On the 2nd of September, Barrie landed his ground forces at Bald Head Cove, a short three miles south of Hampden. With the late hour, the British troops made camp that night. The next day dawned with a damp drizzle and fog. With the riflemen of the 60th in the lead, by seven in the morning the skirmishers started shooting. Lewis, unable to see anything through the fog opened fire with his cannons pointed roughing in the direction of the approaching enemy. It was nowhere near enough, the mere site of the organized British regulars advancing through the fog, the rain drops glistening off the fixed bayonets combined with disciplined volleys saw the militia scatter. Morris and Lewis, seeing that they had no chance against Barrie’s troops and began their retreat. Morris flew the colours from the Adams lighting the charge himself that sent the brig to the bottom of the river. With Hampden captured, the trouble for the locals was just beginning. Barrie made no delay in giving chasing to Lewis and Morris and sailed his squadron to Bangor demanding the town’s immediate surrender along with quarters and supplies with the threat of their destruction.

Looking south along the main road (US-1a) in Hampden, ME the battle would be fought here.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

The town scrambled to comply with the officer’s demands, while that was happening some of the men got their hands on some alcohol, and when Barrie got word of this ordered all the town’s liquor destroyed. This order set off a wave of looting, British soldiers and sailors rampaged through the town looting and destroying property, they even went across the river, burning fourteen ships. The town only escaped further destruction by promising Barrie that they would deliver some of the ships still under construction. A similar scene occurred in Hampden, property destroyed, animals killed for sport, and fearing for their lives the citizens applied to Barrie for a little humanity. The captain scoffed at their request, explaining that he had every right under the rules of war, and while he spared their lives, he would certainly burn their houses. Thankfully he never got around to that. By the time Barrie sailed back to Castine the British invasion had caused an estimated 90,000$ in damages, the British lost two men in the fight with another eleven wounded, seventy Americans were taken prisoner with twelve wounded. In one final act, the British took and destroyed the small fort at Michasport, Fort O’Brien fully securing the coast of Maine from American troops.

Humanity! I have none for you. My business is to burn, sink, and destroy. Your town is taken by storm. By the rules of war we ought to lay your village in ashes, and put its inhabitants to the sword. But I will spare your lives, though I mean to burn your houses. — Captain Robert Barrie

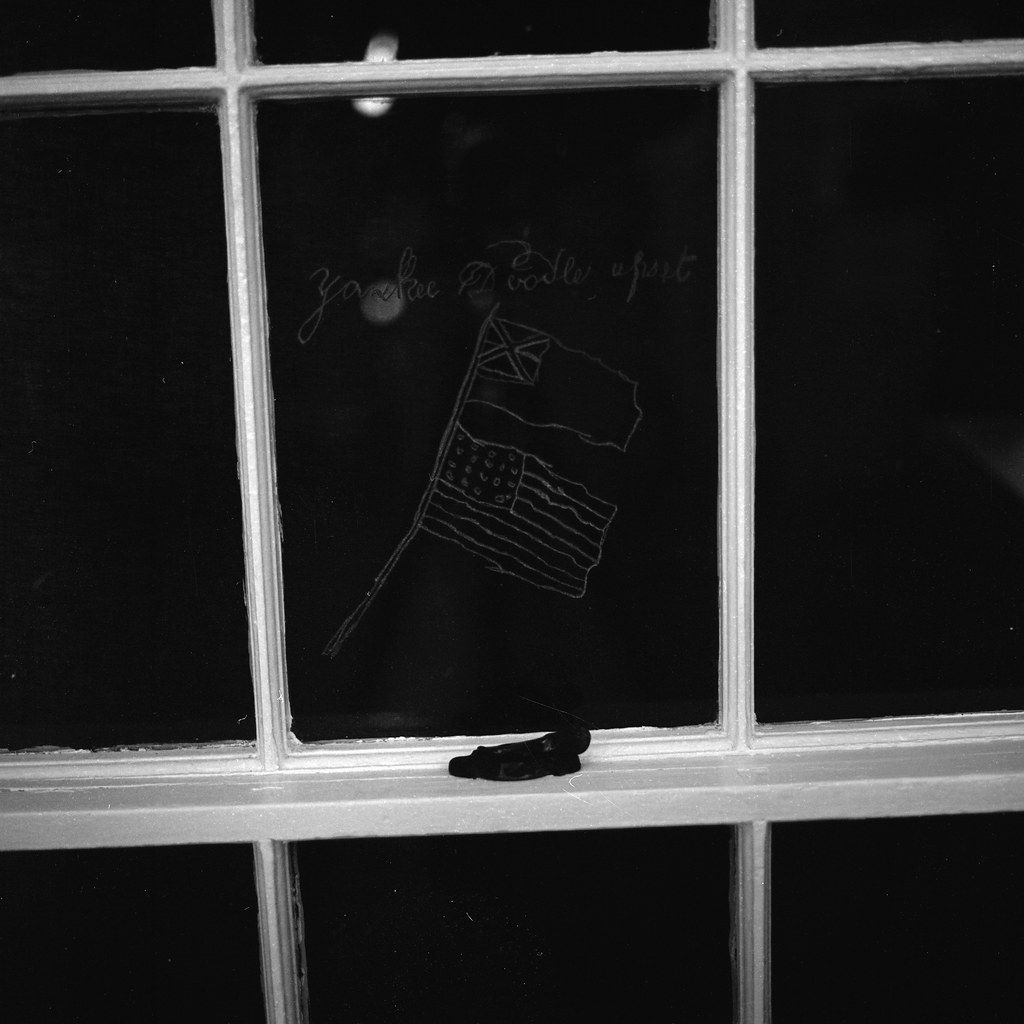

The British occupation would last until 1815. And while the state government did come up with a plan to retake the district of Maine, the governor showed little interest, having little funds or desire to support such an action. The British administration and garrison at Castine were much better behaved, the troops would put on plays for the townsfolk and treated the locals with respect. There was only one recorded instance of vandalism when an officer etched ‘Yankee Doodle Upset’ on a pane of glass in the house he was billeted. When news of the Treaty of Gent arrived, the British destroyed their posts and marched out of the town with much fanfare from the townsfolk. The garrison at Moose Island did not withdraw until 1818. While the Treaty didn’t solve the border issue, the occupation and treatment of Hampden and Bangor left a bad taste in the mouth of the population in the district of Maine. Maine would vote to secede from Massatuchetts and become a separate state under the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Anti-British sentiment would find an outlet in the Aroostook War (1838-39) and the border finally set by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842. The duties paid to the British administration during the occupation would come back to Nova Scotia, the money, known as the Castine Fund would be used to help found Dalhousie College, today Dalhousie University as well as a military library in Halifax.

A lone cannon sits on Bangor’s riverfront, the only reminder that war once came to the town. The cannon dates to the American Revolution.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

It is tough to find information about the Sherbrooke Expedition, even in the areas where it was fought. In Eastport, there’s a sign and cannon marking the site of Fort Sullivan and the wooden barracks now house the local historical museum on Washington Street. Fort O’Brien’s earthworks still stand behind the school of the same name in Miachasport. Castine is home to the greatest number of relics from the occupation, and the local historical society has gone to great lengths to preserve the forts and batteries. Fort Madison/Castine can still be seen with the earthwork battery that was rebuilt during the American Civil War. Fort George’s earthworks and ruins of a casemate and powder magazine now play host to a baseball diamond. And the “Yankee Doodle Upset” etching, while destroyed in 1931 by accident, was recreated by the Castine Historical Society for the bicentennial. In Hampden the old meeting house was destroyed and rebuilt and now is a part of the Hampden Academy the battlefield is now Locus Grove Cemetary. A small grave marks the final resting place of the two British dead in the old burying ground. The Crosby Warf is long gone, but if the water is low enough you can see the remains, but it sits on private property. There’s no evidence that war ever came to Bangor, only a Revolutionary War cannon recovered from the Penobscot Expedition sits mounted on the waterfront behind Sea Dog Brewing. There are no plaques, no markers, and even contemporary guide books focus on Castine for the most part.

A recreation of the famous “Yankee Doodle Upset” etching. The original was destroyed in 1931

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

Special Thanks to the fine folks at the Castine Historical Society for assisting me in the photography for this post. They were helpful in pointing out locations and letting me photograph the replica glass etching. Also special thanks to the kindly woman who owns the property where the remains of the Crosby Warf can be seen for letting me photograph that as well.

Written with Files From:

Collins, Gilbert. Guidebook to the Historic Sites of the War of 1812. Toronto: Dundurn, 2006. Print

Young, George F. W. The British Capture & Occupation of Downeast Maine, 1814-1815/1818. Print.

Hickey, Donald R. Don’t Give up the Ship!: Myths of the War of 1812. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2006. Print.

Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1989. Print.

Lossing, Benson John. The Pictorial Field-book of the War of 1812 Volume 2. Gretna, LA: Pelican Pub., 2003. Print.