From 2012 to 2016, I worked on my most extensive photography and history project, covering almost all aspects of the Anglo-American War of 1812. It remains one of my favourite projects I ever worked on and became virtually a template for a few other projects. Both ones that were finished and published and others that remain in the background as possible for future endeavours. But this year marks the 210th anniversary of the end of the War of 1812, so I have decided to revisit the conflict and present it in a new way. Instead of going deep into details, I’ll show the war through twelve posts, one a month through this year. The idea is to get a better overview of the conflict roughly chronologically rather than an extensive series of posts that dive into deep detail. This series aims to show what happened to start the conflict, including the state of the world that brewed this conflict and its lasting effects even today, 210 years later.

A Note to Readers: This post is going to cover a lot of overlapping and complicated history. I don’t have the time or energy to cover everything in greater detail. Rather I’ll be moving quickly through a period of nearly 100 years in a very short time. This is simply to lay the ground work to the world which birthed the Anglo-American War of 1812.

Nikon FE2 – AI-S Nikkor 85mm 1:2 – Ilford Delta 400 @ ASA-400 – Adox FX-39 II 9:30 @ 20C

Almost a century after the first European settlers arrived in North America, the cotenant was divided between three major powers: Great Britain, France, and Spain. While war plagued Europe and did have an impact on these North American colonial holdings, the local population were often subjected to more minor regional skirmishes. One of the big wars in Europe, the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748), would renew the ancient rivalry between Britain and France over what is today the American Midwest, or Ohio County, which was nominally land claimed by France and Britain. To further these claims, France ordered an expedition of colonial marines, fur traders and indigenous allies to establish trading posts and forts and cultivate relations with the region’s indigenous population. Britain would authorise the colonial authorities to mount similar expeditions into the area. One of the most significant contributors to these efforts was the British colony of Virginia. Both sides tolerated the other until a French party attacked a British post, killing the population and burning it to the ground; in response, Virginia constructed a series of fortified and armed outposts. The governor ordered Major George Washington, an officer in the local militia, to meet with the French to warn them off crossing into Virginian territory, hoping to prevent further violence. While Washington did meet with a representative of New France, it did little to stop the violence from continuing. Despite the efforts, it did not work, and Major Washington soon started fighting the French and their Indigenous Allies by 1754. The conflict soon spread through the other British colonies on the eastern seaboard, and news would get to the home governments. The British had a small force of regular troops and naval ships in North America, and the French had even fewer regular troops and a limited maritime force. Both sides rely on locally raised regiments and civilian militias. Both parties would begin to pour in regular troops and naval ships to support the growing regional conflict. The battles of 1755 would favour the French, but the British would take Acadia (New Brunswick). The regional conflict would go global when Britain declared war against France in 1756. Both sides would form alliances and engage in open warfare across all their colonial holdings. Taking advantage of the new theatres, Britain would send more forces to North America. By 1758, British troops had expelled France from Ohio County, and the British successfully captured the great Fortress of Louisbourg, opening up a route into the St. Lawrence River. The capture was followed up by the capture of Quebec City and Fort Niagara in 1759, which gave the British further access to the Great Lakes. The final city to fall to the British was Montreal in 1760. Fighting would continue sporadically until 1763, when the Treaty of Paris formally ended the Seven Years’ War or, more regionally, the French & Indian War. The terms of the treaty ended French control in North America. While Spain lost Florida to Britain, they gained French Louisiana (which they returned to France in 1801). Great Britain gained all of New France, which they reorganised into the Province of Quebec. Britain and France would end up in severe debt over the cost of the war. Britain now had many more colonial holdings and populations against which to levy taxes. They would also recognise Indigenous claims on the new Ohio territory, allowing them sovereignty through the Royal Proclamation and the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The region’s administration was turned over to the Province of Quebec in 1774, protecting French Civil Law, the French language, and the Roman Catholic Church.

Intrepid 4×5 Mk. 1 – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 – Kodak TMax 100 @ ASA-32 – Kodak Xtol (1+1) 8:00 @ 20C

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

The taxes levied against the population of the thirteen original colonies proved the most annoying; the first such taxes were the Stamp Act of 1765 and left an anti-royalist taste in the mouths of many. Several leaders from nine colonies met to voice their grievances, declaring that their rights as British citizens had been violated and that there should be no taxation without representation. When word of these grievances reached the British Parliament, the home government put in place punitive measures between 1765 and 1768, known collectively as the Townshend Acts. The colonial governors struggled to implement these measures. When word reached King George III, he ordered troops deployed to the thirteen colonies in 1770. The response from the population was swift; a disagreement turned violent when troops fired into a crowd in Boston; the growing rebellion movement labelled it a massacre and only five were killed. In Rhode Island, a mob destroyed a customs schooner in 1772. In 1773, a mob in Boston destroyed 340 crates of tea worth 2.15 million CAD adjusted for inflation. Further punitive measures were implemented, including the ability to quarter troops in people’s homes and the removal of all self-government in several colonies. The rebel movement in the colonies grew, and the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia that same year to organise an armed rebellion against the British colonial forces. Local militias began to seize government weapons, and in 1775, when Regular troops attempted to prevent this seizure, the twin battles at Lexington and Concord opened up the American Revolutionary War. King George III declared the colonies in open rebellion and deployed more troops. A second congress would reorganise the militia into a Continental Army, with George Washington promoted to Commander-In-Chief. Only the thirteen American colonies would sign onto the movement, with the Province of Quebec declining. About one-third of the population supported the rebellion, and another third remained loyal to the crown. Both sides treated the other terribly; the British viewed the Americans as traitors, and vice-versa. Neighbours turned against neighbours, captured troops were not given the same privileges as prisoners of war, and irregular warfare often resulted in the death of soldiers and civilians alike. The Continental forces did see early successes against the Crown Forces, although an attempt to capture Quebec failed. The Rebel Government would meet and declare the King a tyrant and declare their independence in July 1776. The Crown Forces recaptured New York City and Philadelphia in 1777, but Continental forces scored several stunning victories. These victories would allow Spain and France to recognise the independence of the rebel government. However, France would provide financial and military support and declare war on Great Britain. French ships and troops would begin to arrive in 1778. Both sides would fight through the next several years, with the British losing ground and choosing to focus on the southern colonies. The final action of the war would come in 1781 with the capture and surrender of the British forces at Yorktown. While the fighting ended, there was still the threat of renewed attack until the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, ending the conflict. Under the terms, Britain recognised the new United States of America as independent, reliquished all claims on Ohio County, and would turn over all remaining posts to the new nation. Which the crown did, mostly.

Nikon D300 – AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm 1:2.8G

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Pan F+ @ ASA-50 – FA-1027 (1+14) 5:00 @ 20C

France’s economy was shaky after the defeat and loss of New France after the Seven Years’ War. A failed harvest in 1760 combined with overextended the army and treasuring aiding the American Revolution resulted in a high national debt. King Louis XVI needed to increase taxes, and while he was one of the last absolute monarchs, new ideas of revolution and the rights of individuals were starting to take hold. Especially after the Americans overthrew the British powers and formed a republic. King Louis decided to call a meeting of the Estates General in early 1789; the last time this had been done had been in 1614. This pseudo-ruling council comprised delegates representing the three estates, the Clergy, the Nobility, and the Proletariat (the average French citizen). When the Estates met on 5 May, trouble was already brewing on how votes would be cast and counted. The first two estates wanted one vote per estate, giving them the power. The third estate, which would be unequally affected by any increases in taxes, wanted to have each delegate cast a vote, which gave them the majority. When that came to an impasse, the third estate started verifying each of their members to vote and invited the other two estates to copy their example. While some of the clergy would join the people, most stood in horror, even more so when the Third Estate named themselves a ruling National Assembly, declared all taxes illegal and demanded the drafting of a Constitution making the King answerable to the people, taking an oath to stay at the Palace of Versailles until their demands were met. Unaccustomed to such a blatant disregard for his power, King Louis agreed to meet with all of them and settled on drafting a constitution and limiting his power. To some, it was a move too far; to others, it was not far enough; it all depended on the point of view. On 9 July 1789, a new French Constitutional Monarchy was established, and a new police force, the National Guard, was formed with Marquis de Lafayette as the commander. Most welcomed the King as the head of the new constitutional government. But strife and infighting proved to destabilise the government, and fearing a growing anti-royalist movement, the King brought in elements of the Swiss Guard to protect himself and his family. And rumours grew that the Swiss Guard would be sent in to dissolve the National Assembly. In response, a mob formed in Paris, storming the royal fortress and armoury, The Bastille, on 14 July 1789, forcing the surrender of the commandant, who was subsequently executed. The Royal family attempted to flee but were recognised, caught and returned to Paris. A new ruling body, the National Legislature, was formed with a new Constitution, which limited the King’s power even more than the previous document. King Louis accepted the limits on his power, but other powers in Europe were not too pleased. In 1792, several nations formed an alliance and opened the War of the First Coalition 1792. The new government hoped the war would unite the factions in the Assembly, but it only caused further division. In the general public, news of the Brunswick Manifesto that threatened retaliation against the civilian population of France should King Louis be harmed sparked riots and counter-revolutions. The National Guard and Army were called out and often put down these demonstrations with violence. The Assembly struggled to remain in power; the King sought refuge in the Assembly chambers, but a growing anti-royalist group had gained power. They voted to remove the King from power. But without the King, the Constitution proved void, the Assembly dissolved, and a new National Convention was formed on 20 September 1792, which removed all references to the monarchy, declaring France a Republic. The Convention moved quickly to arrest the King, try him for high treason and carry out a summary execution by guillotine on 21 January 1793. The move only widened the war against France. Fearing threats from inside France and without, the Convention formed the Committee of Public Safety. No stone was left unturned, and traitors and threats were found behind every door and corner. Maximilien Robespierre proved to be pivotal in engineering a reign of terror, which saw ten months’ worth of violent stamping out of political rivals, counter-revolutionaries and public enemies as determined by the committee; the terror lasted until 27 July 1794, when Robespierre himself was executed by guillotine. The Convention was soon replaced by a five-person Directory on 26 October 1795. In 1797, the War of The First Coalition came to an end. It catapulted a young General, Napoleon Bonaparte, into the limelight as he used combined tactics in his efforts in Italy. But the peace was short-lived; in 1798, a French Army invaded British-held Egypt with General Bonaparte as its head. The Directory put emergency measures in place, and the Austrians declared war in 1799 thanks to the control of a pro-war faction that controlled The Directory. But a Pro-Peace faction soon arranged for a coupe. Both sides remained at odds with each other, and into the middle came General Bonaparte. Now a national hero and celebrity, Napoleon played both sides. He quietly positioned troops loyal to him around Paris and protected both groups. Both groups feared a coupe and soon found themselves in the middle of one by Napoleon, who marched into the ruling chambers surrounded by loyal troops. The Directory and the Council of 500 found themselves without a choice, and Napoleon installed himself as First Consul of France. While he didn’t hold absolute power, it was an autocratic position with a highly centralised republican government.

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

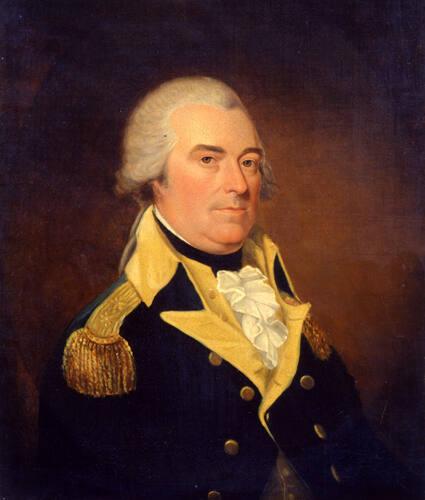

The great American experiment had begun, and while the Revolution had ended in 1783, the new government faced a deeply divided group of states. The latest country faced the growing idea of forming a unified government and figuring out what to do with everything. One thing that had been missed in the peace negotiations was what to do with Ohio County; under the loose British rule, the Territory was nominally administered by the Colonial government in Quebec and technically governed by the indigenous population that lived and stewarded the land. For the American government, these people were allied to the British. The British still maintained a presence in the region, occupying Fort Lernoult (Detroit, Michigan) and Fort Miami (Maumee, Ohio). For the indigenous allies, they felt the British, their allies, had sold them out. When the new States claimed the Territory, it became a mad struggle. It wasn’t without violence, with elements of the Kentucky Militia destroying a Shawnee Village on the Mad River and killing several of the residents. The Federal government would acquire the land from the individual states and put it under Federal control in 1787 as the Northwest Territory. The goal was to purchase the land from the indigenous population for distribution to those wishing to move further west to colonise the region. Some people would sell their land to the Federal government, while others chose to resist. These efforts increased tensions, and both sides began to skirmish against each other. President George Washington would go to Congress to authorise an expansion of the First American Regiment, the small professional army of the new country. Congress reluctantly agreed, seeing the need for a steady, well-trained professional force at the core of a primarily State Militia force to quell the growing resistance in the new Territory. The opening two years of the war did not go well for the Americans. In several cases, they suffered massive defeats on the field against a large alliance of indigenous troops with the backing of the British. President Washington ordered an investigation into the matter. He was already facing internal divisions in his administration and growing concerns over a violent revolution in France. Washington would return to Congress and ask for another increase in the professional army; again, Congress would reluctantly agree. The First American Legion would be given to General Anthony Wayne, who marched the 5,000-strong force to the North West Territory and began intensive training. While the Federal Government still desired a diplomatic victory, any hope of a peaceful end was dashed by 1794. General Wayne marched his army north and quickly engaged and defeated the indigenous alliance, with the decisive victory coming at the Battle of Fallen Timbers that year. The American victory would spell the end of the alliance and force the surviving people to sign the restrictive Treaty of Fort Greenville. The Jay Treaty signed in 1796 forced the remaining British-held posts to be abandoned and turned over to the Americans.

Zena Bronica SQ-Ai – Zenzanon-S 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak Xtol (Stock) 7:00 @ 20C

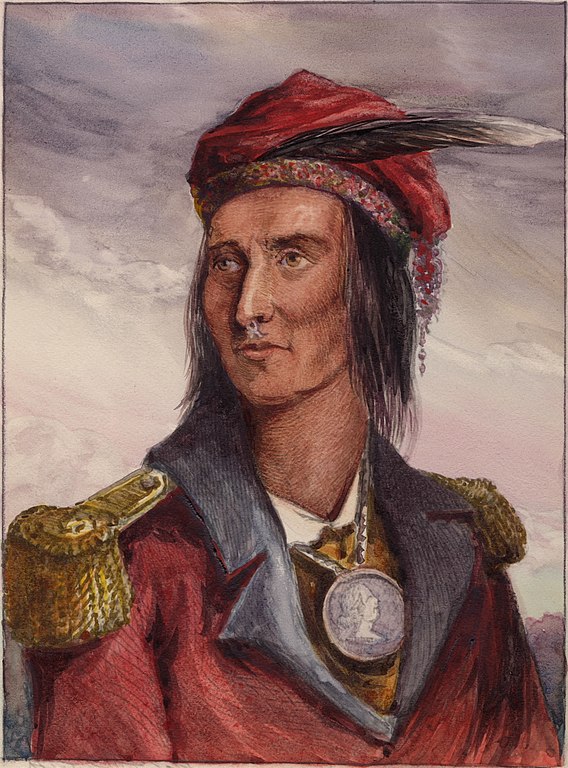

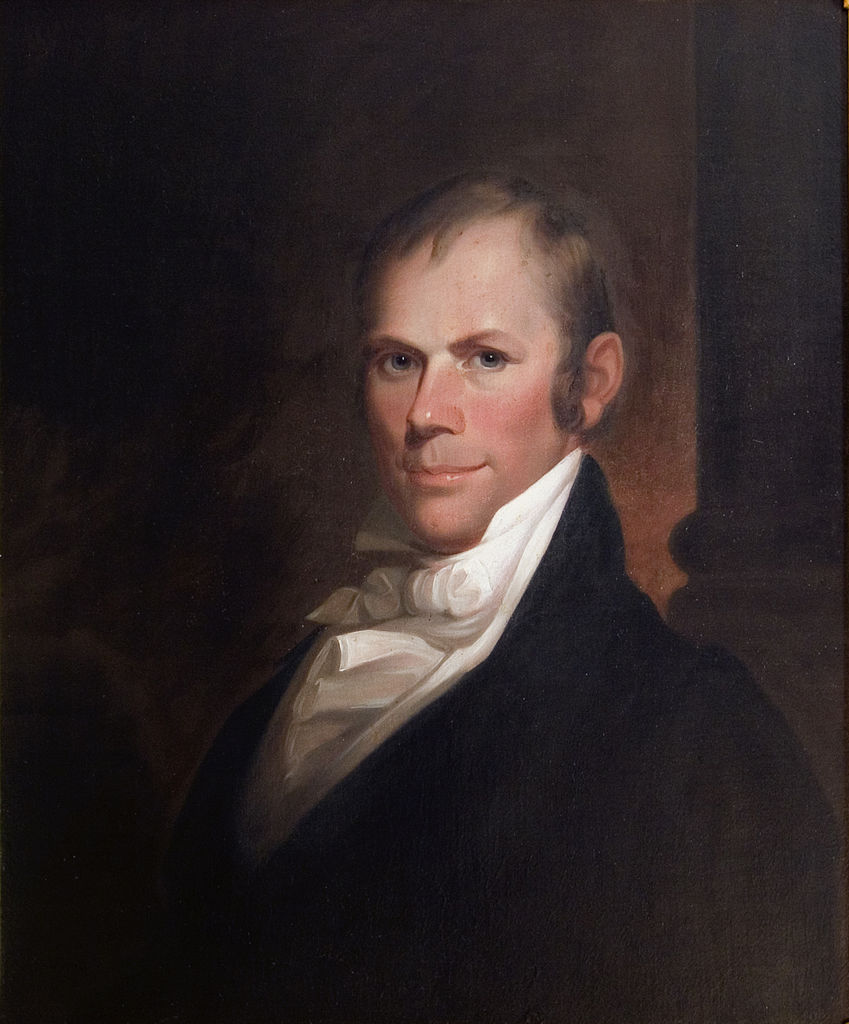

While the treaties ensured some level of peace in North America, the indigenous people or France did not receive them well. The United States and Revolutionary France found themselves in a state of undeclared war, and many indigenous peoples found themselves without land. One of the tribes greatly affected was the Shawnee; many found new homes among the Myaamiaki (Miami) People. The Federal government would quickly reorganise the Northwest Territory into smaller territories and states, including Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. In 1801, the governorship of Indiana was granted to William Henry Harrison, a former aide-du-camp of General Wayne during the Northwest Indian War of the previous century. Governor Harrison was keen on gaining as much Indigenous territory as possible, and he wasn’t above using underhanded tactics to gain those titles. In Ohio, two Shawnees, Tecumseh and his brother Tenskawata, began to teach that all Indigenous peoples were to return to the old ways and that all people were one. The idea of pan-tribalism was not new and had been a vital part of the previous alliance. The two brothers set up a small community in 1803 near Fort Greenville, which directly violated the Treaty signed there. Despite the American settlers’ concerns, they promised only peaceful coexistence. The small community grew with many different people flocking to the teachings of Tenskawata. The teachings called to abstain from drinking alcohol, dressing in European clothing, eating traditional foods and using traditional farming techniques. And they were mostly true to their wish for peace, although some would prove militant. Tecumseh even turned away British agents, refusing an alliance that would have only angered the Americans. However, a naval skirmish in 1807 threatened renewed conflict between Britain and the United States, which saw the community move further south into the Indiana Territory. Harrison would not be pleased when Prophetstown set up on the banks of the Wabash River. Tecumseh again assured the government that he only wanted peaceful coexistence. That is, at least until Harrison negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne. The Treaty had been signed by several peoples, and Tecumseh, who was still only a minor player in the greater picture, had not been a part of the negotiations. Tecumseh would meet Governor Harrison with several warriors who all seemed ready to fight, and it would nearly come to violence if not for quick interventions by one of Harrison’s men and another chief. Both sides would back down, but Harrison became concerned with the large community growing in his territory. Tensions stood on a knife’s edge, and when Techumseh headed south to try and bring members of the Muscogee into his confederation, Harrison wrote to Washington asking for advice. Harrison had already declared Tenskawata a fraud, which angered the Indigenous leader, who many saw as a prophet. While Techumseh had urged caution, Tenskawata had called for Harrison’s death and even lifted the ban on firearms, securing several British muskets for the community. Harrison would receive permission to disperse the Prophetstown population by force if the need arose. Harrison marched south with an armed force of regulars and militia troops under his command. He set up camp where the Tippecanoe and Wabash Rivers met. The two agreed to meet, but even after the meeting, both sides remained wary. Tenskawata thought Harrison was planning a sneak attack and launched a surprise attack on the American encampment. The attack was brief, and while initially surprised by the sudden attack, Harrisons troops stood their ground and eventually drove the indigenous forces back. Then, they pursued them to Prophetstown, where they destroyed what was left and dispersed the surviving population. When Tecumseh returned, he found nothing but ruins; gathering up what survivors of the confederation he could, he headed north for Upper Canada.

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Formulary Developer 23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Formulary Developer 23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

When we last saw France, Napoleon Bonaparte, the hero of the War of the Second Coalition, which had wrapped up with the peace of Amiens in 1802, had installed himself as First Consul of the French Republic. Napoleon used the peace to spread French influence over the European continent, much to the annoyance of Great Britain. Napoleon would also annoy the British by selling French Louisiana to the United States that same year for a very good price, which doubled the new country’s size overnight. These actions pushed Britain too far, and they openly declared war on France in 1803. Both nations quickly gathered their allies, starting the war of the Third Coalition. During the war, Napoleon would wipe away any trace of the French Republic, dissolving the Holy Roman Empire and declaring himself Emperor of the new French Empire in 1804. While Napoleon would wipe the floor with the allied armies on land, the Royal Navy would clean the clocks of the Franco-Spanish Fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Although Napoleon would win the decisive victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1806, forcing a peace treaty. During the pause in the fighting, Napoleon would redraw the map of Europe, setting up puppet states that were friendly to the French Empire. Not pleased with France’s increased influence, Prussia started the short-lived war of the Fourth Coalition, which resulted in the capture of Berlin by Napoleon’s forces in 1806. Napoleon, still trying to suppress British influence in mainland Europe, started the Continental System, banning trade by the member states with Great Britain and invading Portugal, the only ally left of Britain on the mainland, in 1807. In response, Britain set a series of laws blocking trade with France by any of their trading partners. The Royal Navy would blockade French ports along with the ports of any of France’s trading partners. This economic warfare put the United States in a troubled position as they were active trading partners with both parties. The American government would launch a series of laws to reduce the country’s reliance on trade with Europe. Which stimulated and industrialised the northern states. Britain would launch an invasion of occupied Portugal in 1808, landing a large force under General Arthur Wellesley, who quickly turned back the French troops, pushing them back into Spain. Fearing Spain would turn and ally itself with Britain, Napoleon deposed the Spanish King, installed his brother as the new King and started a war in Spain to occupy the country. An army under Sir John Moore would pursue the French into Spain. Still, due to bad weather, logistics, and luck, they were forced into a disastrous retreat followed by another invading French army. While the French maintained some control over the nations, they faced constant engagement from loyalist Spanish armies, a mixed Portuguese and British army, and partisans. A short-lived Fifth Coalition gave the British time to reform their armies under General Wellesley, return to Portugal, and fight to remove the French by 1810. With France completely controlling Spain, both sides fought to a standstill by 1811. But with British naval dominance, improved supply lines, and the French under constant threat from Spanish partisans, Wellesley would invade Spain, fighting one of the longest, bloodiest sieges in the year’s first half. By the summer, the British had achieved a comfortable beachhead in Spain, and Napoleon was turning his eyes to Russia.

Nikon F5 – AF DC-Nikkor 105mm 1:2D – Ilford Delta 100 @ ASA-100 – 510-Pyro (1+100) 10:30 @ 20C

Nikon D750 + AF-S Nikkor 70-200mm 1:2.8G

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

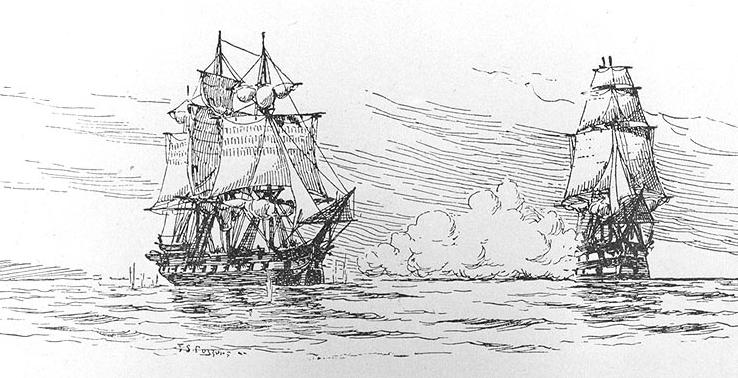

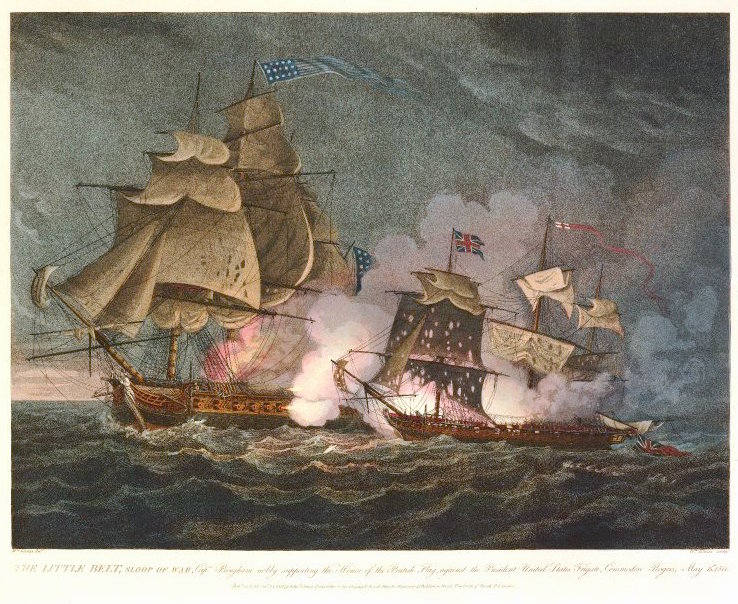

There was no singular cause for the American declaration of war against Great Britain in the summer of 1812, and the entire thing could have been easily prevented. But in the end, it all came down to national honour, something that a large group within the American government felt the British had continued to stomp on through their actions since the end of the American Revolution. These War Hawks saw the actions of the British in the Northwest as stirring up trouble within the Indigenous population against the Americans. It also didn’t help that in the Northwest Indian War, the British openly supplied weapons to the Confederacy and even, in some cases, fought alongside the troops. British muskets had been found at Tippecanoe, which further pushed the Americans towards war. And then there were Great Britain’s actions with their war against France. The might of the Royal Navy was the only thing that could keep Napoleon in check, and the Royal Navy needed men; often, these men were taken without consent in what is called impressment. Mostly, British men would be pressed into the service. If a ship at sea was captured and the ship doing the capturing needed men, they did not care about citizenship. This would lead to two incidents where the British learned the hard way not to touch American ships. The first occurred in 1807 when the British searched for four deserters from their ships at the North American Station. When the British ministry in Washington learned that the men had signed onto the US Navy at the Gosport Naval Yard, they demanded their return. Many US Naval establishments would ignore such requests and give sanctuary to anyone who came looking for work as a US Sailor. The yard’s commander delayed his response, giving enough time for the men to sail aboard the newly minted US Frigate Chesapeake. When the Royal Navy learned of this, they sent the HM Frigate Leopard to intercept. When the two ships met, the Leopard signalled for the Chesapeake to heave and prepare to be searched, something the American captain refused. The Leopard then fired across the Chesapeake’s bow, and when she again refused to stop, she fired directly into the ship with a full broadside. The battle proved short, and the Americans managed to fire a single gun before surrendering. A boarding party secured the four men and returned to the Leopard. Of the four, three were natural-born Americans; these were sentenced to five hundred lashes (a death’s sentence), while the fourth, a British citizen and deserter from the Royal Navy, was returned to the ship he deserted from and hanged from the yard arm until dead. The American government threatened war over the actions of the Leopard’s captain, but the British (busy with Napoleon) commuted the sentences of the American sailors and returned them to Boston Harbour unharmed. The whole thing was smoothed over, and the Royal Navy cut back on impressment and backed off from the American ports. At least until the HM Frigate Guerriere decided to board the US Sloop Spitfire and press their sailing master into His Majesty’s Service in 1811. The US Navy deployed the US Frigate President to intercept the Guerriere. When they saw a ship on the horizon, they closed for battle. The Americans thought the ship was the Guerriere and quickly closed, misreading the signals. The ship they had intercepted was the HM Sloop Little Belt. The Little Belt stood no chance against the powerful American Frigate and soon was defeated. Both captains and governments painted each other as the victim of the affair. But neither side was ready to take the blame. While the British Parliament would start to move the needle on how they were conducting their war with Napoleon, it was too little too late and too far. By May 1812, the Americans were moving armies into position and laying out a plan of invasion against British North America. A declaration of war was being made by the American government. The die had been cast, and it would soon end in fire.

While this post has covered a lot of subject matter across a wide range of history, there is still plenty to see and visit today. The reconstructed Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia is well worth a visit. You could even spend an entire day here without worry. The Plains of Abraham are dotted with memorials and sit outside Old Quebec City’s walls, giving you a sense of the scale of what the British Forces had to climb to get up to defeat the French. The remains of a French Fort can be found in downtown Kingston, and Fort Rouillé is marked by a memorial on the CNE grounds in Toronto. Fort Niagara in Youngstown, New York, is home to the oldest military buildings in the area and is well worth a visit. A single blockhouse survives from Fort Pitt in Point State Park in Pittsburg, PA. Moreover, several vital forts, such as William Henry, were reconstructed. Memorials to the American Revolution are many across the United States. I’ve had the chance to visit the Bunker Hill memorial in Boston and Valley Forge in Pennsylvania, and you can find memorials similar to those of the attempted invasion of Quebec in Quebec City and Montreal. A cannon from the ill-fated Penobscot Expedition is found in Bangor, ME. The ruins of the British fort in Castine from the same period are still visible. Europe is covered in the reminders of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. A memorial to the Battle of Fallen Timbers can be visited in Maumee, Ohio. The Tippecanoe Battlefield is covered in grave markers from the American dead and dominated by a memorial; the former site of Prophetstown is now a state park and has both an American colonial settlement and a replica Indigenous settlement; all three are located near Lafayette, Indiana. In the case of all these periods, there is an active reenactor base. At the same time, most are focused on the American Revolutionary and Napoleonic Periods; some French & Indian Reenactments occur at critical sites. The novel Last of the Mohicans is written about the French & Indian period and there is also a film by the same name that presents a rough approximation of the Siege of Fort William Henry. Additionally, the musical Hamilton gives an interesting take on the American Revolution in the play’s first act. Bernard Cornwall has written several novels set during the opening stages of the Penisular War in his popular Sharpe Series, and also The Fort which takes place during the American Revolution and the Penobscot expedition.