The first six months of the war had not gone as planned for the United States. Rather than a swift capture of Amherstburg, Niagara, and Kingston, the swift actions of the late Major-General Sir Isaac Brock resulted in the capture of Mackinac Island, Fort Detroit and Michigan Territory down to the River Raisin, and a repulse of the invasion across the Niagara River which cost him his life at the Battle of Queenston Heights. The death of General Brock was a significant blow, as his replacement, Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, proved to be a far less effective administrator and military leader. It got bad enough that the Governor General, Lieutenant-General George Prevost, would have to leave Quebec City to visit Upper Canada to fill in while General Sheaffe was ill. In the United States, the bitter taste of defeat had left a fire to renew efforts in 1813, mainly spearheaded by the new Secretary of War, John Armstrong Jr, who also began to work with younger officers who were not relics of the American Revolution, but also had to work with an older general like Major-General Henry Dearborn and reign in Major-General William Henry Harrison. Armstrong’s new plan called for a combined effort by the army under General Dearborn and the Lake Ontario squadron under Commodore Isaac Chauncy to launch a strike against Kingston and blockage the St. Lawrence River to cut off support from Lower Canada and the Maritime Provinces. But the winter 1813 proved rough, and the lakes and rivers were frozen. Any attack would have to wait until the spring.

Graflex Anniversary Speed Graphic – Kodak Ektar f:7.7 203mm (Yellow-15) – Kodak Plus-X Pan @ ASA-125 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 5:00 @ 20C

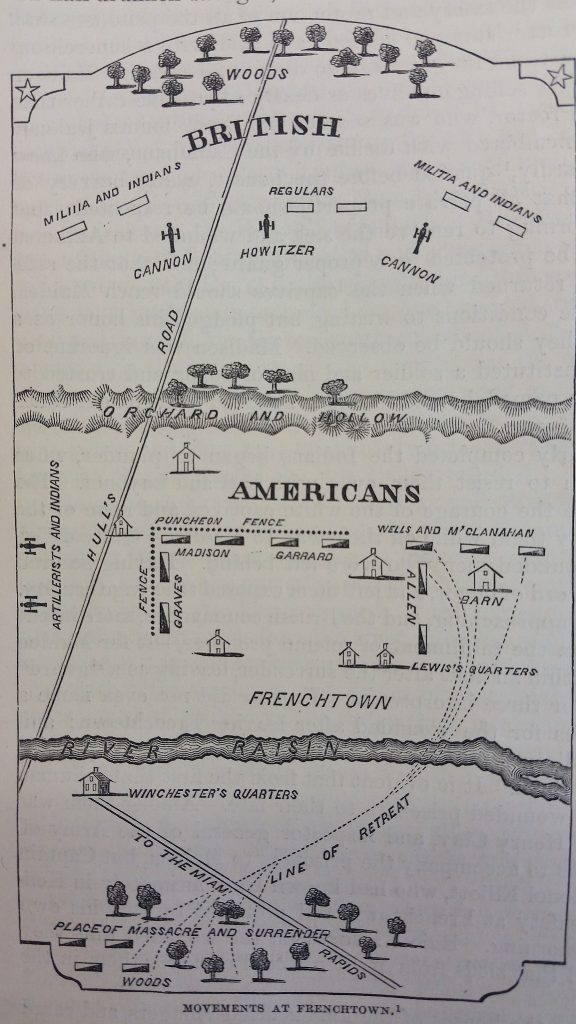

Out in the west, General Harrison had been tasked with breaking through the British lines and recapturing Fort Detroit. But Harrison had been left with an army in shambles and was forced to rebuild and retrain a batch of fresh recruits. While Harrison would make his headquarters in Sandusky, Ohio, he ordered his second-in-command, Brigadier-General James Winchester, to make camp within marching distance on the southern bank of the Maumee River, today a part of Toledo, Ohio. Winchester commanded a brigade of mainly militia troops recruited from Kentucky,, including musket and rifle-armed units. It was at his camp that Winchester received a visitor who had walked some twenty miles from the small settlement of Frenchtown. The civilian asked for help to dislodge a British outpost in their community. Without orders from Harrison, Winchester ordered Lieutenant-Colonel William Lewis to take most of the troops north to force the British out of Frenchtown. On 18 January, Colonel Lewis’ force crossed the River Raisin, and despite having no combat experience, the numerical superiority of the American force could easily force the withdrawal. The outpost had only a body of Essex militia and Potawatomi and were easily outnumbered, but made the Americans fight for every bit of ground, beating a fighting retreat out of the town. The militia troops would head north to report the push by the Americans, and the Potawatomi would burn the small hamlet of Sandy Creek on the retreat. Winchester would march his remaining troops north to fully occupy the town but left vital supplies at the Maumee River. When General Harrison learned of the move, he sent four companies of regular army troops from the 17th and 19th US Infantry Regiments under Captain Nathanial Hart. Both Winchester and Hart arrived in Frenchtown on 20 January; Winchester set himself up in the Navarre House as headquarters, leaving no instructions to set up field fortifications. Despite word that a large force of British troops had crossed the river under Colonel Henry Proctor and were headed south. Proctor had assembled members of the 41st and Royal Newfoundland Regiments, local militia, a large group of Indigenous troops under Tecumseh, Roundhead, and Walk-In-Water, all accompanied by six sledge-mounted cannons. Proctor’s army faced no resistance and managed to make it within a few miles of the settlement as Winchester set no advanced sentries. Attacking after dawn on 22 January, the British were able to almost completely form up and get within musket shot before the Americans were even aware they were under attack. The green troops stood under withering volleys and artillery fire for nearly twenty minutes. They managed to deal some damage against the British before cutting and running back in disorder. Having assumed this, Proctor had sent Roundhead around the American flanks to cut off the American retreat. Winchester, who had finally awoken, sent Captain Hart’s regulars forward. The general retreat forced many, including General Winchester, back along the narrow road. The waiting Indigenous troops attacked with such violence that even General Winchester found himself a prisoner. Stripped of his uniform, he was brought before Colonel Proctor. Colonel John Allan managed to rally his troops. He continued to put up a fight, his riflemen taking out two gun crews of Proctor’s center guns. Hoping to force the issue, the British line charged in three times, each time being thrown back by the Kentuckians, who had managed to get some form of cover. Winchester and Proctor haggled back and forth on surrender terms and were impasse. Only the intervention of Major George Madison of the Kentucky militia and the suggestion of protection from the Indigenous troops made the two men agree. The defenders were confused when a British officer approached the line under a flag of truce, and their confusion turned to indignity when the surrender orders were delivered. Colonel Allan said his troops were willing to die rather than become prisoners of the Potawatomi. The fighting continued for another three hours when the lack of ammunition and the intervention of Major Madison the ,last of the militia surrendered. Fearing a swift response from General Harrison, Proctor had no intention of securing the town and ordered his troops to round up the prisoners who could walk and march north. Those who were too wounded were left at Frenchtown with the promise that sledges would be sent for them the following day. Only the next day the wounded were awoken by an unfriendly group of Potawatomi, having rifled and stolen the surviours belongings, those who would walk were forced out into the snow, those who couldn’t were killed and the buildings set to the flame. The road north would become littered with bodies as several wounded were unable to keep up and were killed; the exact numbers could be as low as thirty to more than one hundred. The actions at Frenchtown resonated with General Harrison and Kentucky, and a new recruiting drive called on the population to remember to Raisin and further drove a wedge between the American population and the Indigenous population. Harrison would be forced into a more defensive stance, having wanted to start making hit-and-run raids into Upper Canada, which were put on hold. Harrison made plans to fortify northern Ohio and restarted the construction of several forts, including a large depot fort on the Maumee River.

Bronica SQ-Ai – Zenzanon-S 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak Xtol (Stock) 6:15 @ 20C

Bronica SQ-Ai – Zenzanon-S 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak Xtol (Stock) 6:15 @ 20C

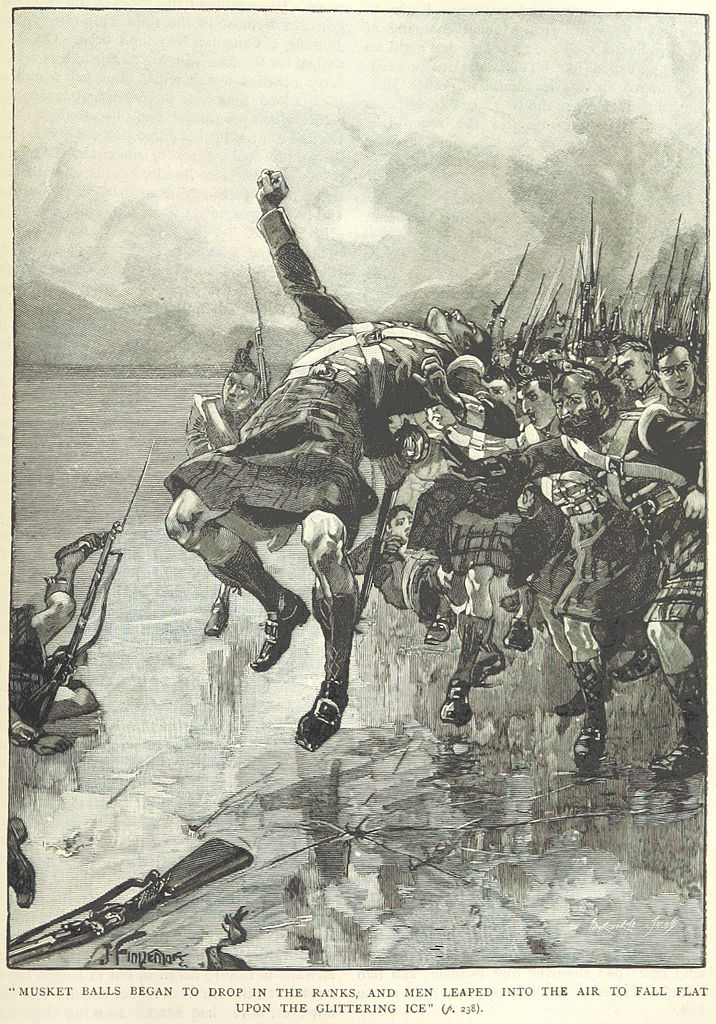

The St. Lawerence River had since the fall of 1812 become an active battleground, thanks mainly to the proximity to the two shores and a series of raids and counter-raids had left a rather sour taste in the mouths of the civilian population on both sides of the river. While the raids started focusing on the theft of supplies, a raid by the garrison at Prescott on 4 February across to Ogdensburg had resulted in the theft of supplies by a few prisoners. When Major Benjamin Forsyth moved from Sacketts Harbor to Ogdensburg, he learned of the recent raid and the capture of prisoners. He set out to rescue the men and conduct a counter-raid. Forsyth, his 1st US Rifle Regiment, and a handful of New York militia moved first by sledge to Morristown before crossing the river on 7 February under darkness. Having learned the prisoners were being held in Elizabethtown (Brockville), quickly took the town, killing one sentry and suffering a single loss before forcing the local garrison to surrender and occupying the town’s courthouse. Forsyth released the prisoners, gathered up what supplies he could and secured the entire garrison as prisoners, then ordered the town’s barracks burned down and crossed the river without incident. Word of the counter-raid would reach General Prevost. At the same time, he travelled to York with additional regular troops to reinforce Upper Canada’s garrisons. However, the soldiers from Quebec City were not the only ones moving towards Upper Canada. The newly formed 104th (Royal New Brunswick) Regiment of Foot began the long departure from Fredericton, New Brunswick, on 16 February; leaving at a company per day, the men would march single-file on snow shoes ten miles each day, setting up camp then repeating this feat the next day. General Prevost stopped in Prescott on 20 February; he left a handful of troops there to bolster the garrison in light of the raid. He also left orders with the local commander, Lieutenant-Colonel George MacDonnell, that should the American garrison at Ogdensburg see a reduction, he could launch a counter-raid to free the prisoners and recapture the stolen supplies. After Prevost left, MacDonnell found himself with elements from his regiment, the Glengarry Light Infantry, forces from the 8th (King’s) and Royal Newfoundland Regiments, and local militia. Plenty to conduct a raid against the American garrison, MacDonnell wasted no time and, on 22 February, marched his force out onto the ice of the river along with a pair of cannons. The sight of the British garrison drilling on the ice was not a strange sight for the residents of Ogdensburg. The force is split into two separate columns. The attack was already off to a bad start as the pair of guns (which were not mounted on sledges) had gotten bogged down in the snow. The local militia scrambled to operate the batteries to defend the town. When MacDonnell’s column hit the American shore first and quickly overwhelmed the shore battery, the militia fell back in good order. It forced the British into street fighting, slowly drawing the column into a trap outside the town armoury on Ford Street, where a six-pound cannon had been set up. The second column under Captain John Jenkins hit the shore facing the old French fort on the town’s outskirts; here, Major Forsyth had taken his men into a series of small stone buildings where they easily held off the British column, causing a great deal of death. Without cannons, the British were forced to use small arms against the fortified position. The initial charge had wounded Captain Jenkins and left Lieutenant James Macauley in command to fight to a standstill. MacDonnell managed to dislodge the militia and now marched to the rear of Forsyth’s position and demanded the garrison’s surrender as they were now surrounded. Forsyth had no plans to surrender to become a prisoner and ordered the militia to create a diversion. With the militia now lining up for a counterattack, Forsyth slipped his riflemen out of the town as the militia put up a show before surrendering. The British would loot several homes (along with the militia) in the general confusion following the initial stop to the fighting, and a few schooners burned in their stocks. MacDonnell would agree to return the stolen private property with the return of the stolen supplies and release of the prisoners. The local community leaders also agreed to prevent the return of any garrison to Ogdensburg. That influence prevented Forsyth from launching a planned counter-attack. The two communities enjoyed a pocket of peace and mutual trade. When General Prevost learned of the attack and, more specifically, the success of it, he adjusted his journals to show that he had already approved the attack.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak Plus-X Pan @ ASA-125 – Kodak TMax (1+4) 5:45 @ 20C

Hasselblad 500c – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

By 15 April, the first companies of the 104th were arriving in Quebec City, having completed their march in record time. But their journey was far from over; they were waiting for the winter ice on St. Lawerence and Lake Ontario to thaw before they could continue by bateaux to Kingston and garrisons across Upper Canada. Also waiting for the thaw, a force of 7,000 American troops at Sacketts Harbor. But the plan had changed; despite counter-intelligence, General Dearborn and Commodore Chauncy believed that the Kingston garrison easily outnumbered their invasion force and that such an attack would result in a crushing defeat. They wanted an easy and symbolic victory to boost the flagging morale. Dearborn and Chauncy would convince Secretary Armstrong that York, the provincial capital, would make the perfect target for such a victory. Armstrong agreed and authorised the change, and the American commanders were not wrong. Despite being the capital of the province, York was sorely under-defended. When John Graves Simcoe established York as the capital of Upper Canada, he felt that the distance between the city and the US border was enough of a defence. The main garrison was east of Garrison Creek, with a blockhouse at the mouth of the Don River and a second one on Gibraltar Point. On the western bank of the creek stood the grand magazine for the garrison and the Government House. In 1806, General Brock had ordered the construction of an artillery battery near the government house, a smaller battery near the ruins of Fort Rouille and a battery further west. Brock also established artillery batteries and additional earthworks at the garrison to be constructed. The trouble was that the garrison lacked cannon, and even had several cannon that dated to the English Civil War and had to be lashed to carriages as the guns lacked the trunnions needed to secure them properly. General Sheaffe also lacked troops; many of the soldiers at the garrison were either moving further east or west, with regular troops, local militia, and Mississaugas making up the small garrison. On 26 April, the signal sounded from an outpost on the Scarborough bluffs that a large squadron of American ships had been sighted. General Sheaffe hurried to position his troops, placing most regulars around the blockhouse on the Don River, and ordered the militia to be called up and ready to defend. Leading the invasion from his new flagship, US Corvette Madison, Commodore Chauncy and General Dearborn had placed command of the landing force with Brigadier-General Zebulon Pike. With the US Brig Oneida supporting several small schooners, the shores were swept with artillery fire into the woods. As the landing craft moved in close, they were peppered with fire from the Mississaugs occupying the woods. Major Forsyth and the 1st US Rifle Regiment would be the first to land under harassing fire. The riflemen were also well-versed in the same type of irregular fighting in the forest. Between the rifle fire and cannon fire, the Mississaugas were forced back. Sheaffe quickly ordered the regular troops from the town site and sent the Glengarry Light Infantry to support the Mississaugas. But light troops were misdirected by the local Adjunct-General of the militia, Æneas Shaw, who was slowly forming the local militia. The delay allowed more Americans to land, and with the riflemen in pursuit, the Mississaugas came out into a clearing around the old French fort where Captain Neil McNeale had formed up his grenadier company of the 8th (King’s) Regiment. The crashing volley sent the riflemen back into the woods, giving them cover to start quickly picking up the British troops. After the captain was killed, several officers took charge and made attempts to drive the Americans back, but they met with the same fate. It was a sergeant who managed to get the men lined up and charged into the woods, only to be killed and the line thrown back.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

General Sheafe had formed a new defensive line at the Western Battery but soon found his line mixed up with the wounded from the initial efforts to halt the American advance. More troops were now moving forward towards the garrison. In the chaos, a spark ignited the portable magazine; the resulting explosion forced Sheaffe to fall back to the garrison, leaving the Americans a clear path. Sheaffe would watch as the American artillery lined up; the militia would form up in the ravine behind the garrison but refused to move, fearing an American flanking move to take the town. Deciding his position was lost, Sheaffe ordered the magazine destroyed along with the HM Sloop Sir Isaac Brock, under construction at the King’s Warf, burned in her stocks. Then, the regulars and fencible troops were formed, and they went west to Kingston with orders for the militia officers to arrange the best terms of surrender with the Americans. In the confusion, the flag was left flying, so when General Pike showed up, he assumed that the garrison was still defended and moved in. The explosion of the grand magazine could be felt at both Fort George and Fort Niagara, withThe commander of Fort Niagara noted in his journal that the windows of the French castle shook with the shockwave. Rock, shot, and fire came down in a wide radius, killing or wounding both British and Americans, among them General Pike. The angered Americans rushed in, only to meet three militia officers under a flag of truce. Colonel William Chewett, Major William Allan, and Captain John Robinson met with Major George Mitchell to discuss the terms of the surrender. The Americans were quick to round up any survivors, holding them in the town blockhouse. Major Forsyth would be ordered to set a guard on the town to enforce General Dearborn’s and General Pike’s orders to protect private property. The negotiations were not off to the best start, with the mortal wounding of General Pike,, the destruction of the magazine, the Sir Isaac Brock, and the burning of the bridge across the river, all while the flag still flew over the garrison. Eventually, the officers agreed, but Major Mitchell did not have the authority to sign the surrender agreement. Several Americans left the garrison that night and made it into the town, but it only caused some damage. But when the surrender order remained unsigned the next day, the city faced full reprisal. American troops looted without any concern for the general order, private homes, stores, the library, and even churches. American troops also raided the Parliament buildings of the mace of office, the speaker’s wig and a golden lion statue. The town jail was opened up, and prisoners would also make it to the Parliament buildings and set the building ablaze. On 29 April, a furious rector, Reverend John Strachan, demanded to speak to General Dearborn and Commodore Chauncy aboard the Madison. Reverend Strachan accused the officers of purposefully delaying the signing of the surrender order to facilitate the town’s destruction. It is unknown if the minister’s fury contributed to it, but the order was signed. The American occupation saw any surviving military supplies transferred to the American fleet, required medical care given to the wounded British soldiers, and the local government was allowed to maintain order. But the Americans began to feel ill at ease. They tried quickly to end their occupation, but the weather remained uncooperative.

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

Pentax 645 – SMC Pentax A 645 75mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:45 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

Major-General Henry Proctor also faced troubles; he had been ordered to launch an attack against Fort Presque Isle, where since 27 March, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry had been constructing a Lake Erie squadron for the US Navy. But he lacked the required men, ships, artillery, and supplies to assault such a target or even General Harrison’s headquarters at Sandusky. Instead he could only try and delay any action by General Harrison by attacking the depot forts in northern Ohio. Despite being the largest of Harrison’s depots, the fort’s garrison stood at less than one thousand men. General Proctor would leave Amherstburg while York was under attack, landing a force of regulars, militia and Ingenious troops at the mouth of the Maumee River and marched inland. When Harrison learned of the landing of the British army, he ordered three hundred more troops to garrison the fort and convinced the governor of Kentucky to send Brigadier-General Green Clay north with some 1,200 new militia troops. Proctor would establish most of his artillery batteries along the northern shore of the Maumee River, with two south of the fort and opened fire on the fort on 1 May. Harrison hastily ordered tall traverses be erected inside the fort walls to defend against the bombardment, the traverses along with the soaking rain meant that the shot simply sunk into the mud. Harrison, not one to wait, ordered General Clay to attack the British batteries north of the River. At the same time, he sent a sortie out from the fort to attack the batteries to the south. On 5 May, Colonel William Dudley landed on the northern bank of the River, making his way under the cover of darkness quickly overwhelmed the lightly defended artillery batteries. But waiting in the woods were Indigenous troops who jumped the Kentuckians, ready to take their revenge; Colonel Dudley lost all control as his militia troops chased after their enemy, leaving only ramrods to spike the guns. Dudley would leave Major James Shelby to hold the batteries while he went after the troops. Across the River, Colonel James Miller met with similar success, easily overpowering the small force at the batteries and driving the attackers back. But the nose of the action had raised the alarm, and Proctor ordered two forces of troops out to retake the batteries. Colonel Dudley and many of his troops would meet their end in the skirmishing in the woods, and survivors were taken prisoners by the Indigenous troops. Major Shelby soon faced down Major Adam Muir who made quick work of the remaining American militia. Colonel Miller gave Captain Richard Bullock more of a fight before being forced back to Fort Meigs. Only a small number of troops from Dudley’s brigade made it back to Fort Meigs, many were killed but a large group were taken prisoners by the Indigenous troops and taken to the ruins of Fort Miamis outside the main British camp. The animosity between the two groups was on full display when the Indigenous troops began to torture and kill the American prisoners; in the middle of that, Tecumseh went to General Proctor to try and get him to stop the killing; what happened between the two is vague and often told with Tecumseh insulting Proctor. But when Proctor refused to stop the violence, it took the combined efforts of Tecumseh, Lieutenant-Colonel Matthew Elliot and Captain Thomas McKee before the Americans were left alone. The ineffective artillery bombardment between the two lines continued, as did the miserable spring rains. A prisoner exchange was arranged on 7 May, and those survivors were returned to their appropriate camps. The barrage continued until 9 May and fought to a standstill. Proctor reduced to only his regular and militia forces returned home to Amherstburg.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Delta 400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Delta 400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:30 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Ilford Delta 400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+4) 6:30 @ 20C

The last American troops left York on 8 May, and the ships filled to the brim with military supplies and some personal belongings looted from York. Returning to Sacketts Harbor to rest, rearm and reinforce from the losses taken in destroying the capital would take several weeks. It also allied with General Dearborn’s new chief-of-staff, Colonel Winfield Scott, to implement several reforms in the US Army, improving the logistics of moving supplies. Also arriving at Sacketts, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry asked for additional sailors and supplies for his squadron on Lake Erie. Perry, officially a Lieutenant, was pushed into the service of mapping out the shore of Lake Ontario for a landing zone of the next target, Fort George in Niagara. Brigadier-General John Vincent, the commander of the British forces in the area, had an idea that an attack against Fort George was coming; it had been only logical after the attack on York. The trouble was that, like the year before, he did not know where the Americans would land and didn’t have enough troops to defend the entire frontier along the Niagara River. He had positioned most of his forces at Fort George, with detachments at Queenston, Chippawa, and Fort Erie. When the American guns at Fort Niagara opened on 25 May, Vincent assumed that any attack would come from across the river, covered by the artillery at the fort and the shore batteries. Several shots were heated red hot and set fire to the wooden buildings inside the fort’s wall and in the town. The British batteries along the shore also noted that a large number of sails were on the horizon; Vincent rightly assumed these were the ships of Chauncy’s squadron and sent a dispatch to General Prevost and Commodore James Lucas Yeo at Kingston that Sacketts Harbor would be largely undefended with the squadron tied up in the Niagara area. As the morning fog lifted on 27 May, the first boats pulled towards Lake Ontario’s shore, and the schooners Perry commanded moved in close behind. Chauncy’s big ships, the Madison and Oneida, suppressed the shore batteries first. The first wave, commanded by Colonel Scott and Major Forsyth, hit the group. Even before they waded onto dry land, they were met by a group of Glengarry Light Infantry. They engaged in deadly hand-to-hand combat that officers and soldiers alike were forced to defend themselves. But as more American troops landed, the defenders were forced back. Scott signalled for the schooners to move in closer as the defenders charged in again, the Glengarry now reinforced by the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. But this time, Perry’s schooners were ready. They peppered the shores with grapeshot, sending the defenders back to a ravine on the other side of the town where General Vincent had gathered the main body of troops, mainly from the 8th (King’s) Regiment and the local militia. The delay allowed the remainder of the invasion force to land, two brigades commanded by Brigadier-General John Boyd and Brigadier-General William Winder. Scott also arranged for a group of the 1st US Dragoons under Colonel James Burns to land on the other side of the fort to cut off any chance of escape. The British shore batteries proved effective in delaying their crossing. As the first group of Americans passed through the town, the defenders launched a counterattack, pushing the Americans back into the town, forcing street-to-street fighting, and nearly getting them back to the landing area only to find themselves outnumbered and pushed back into the fort itself, which was now under bombardment by the Madison and Oneida. General Vincent,,, now desperately outnumbered,ered the fort’s magazine destroyed and batteries spiked. But the sudden reversal saw Vincent arrange a hasty retreat to Queenston, leaving the fort almost totally intact, with only a tiny magazine detonating wounded a handful of Americans, including Colonel Scott. Scott arranged for a quick pursuit of Vincent, where he linked up with Colonel Burns; only the timely arrival of Captain William Hamilton Merritt and his Provincial Dragoons allowed most of Vincent’s troops to escape. Scott and Burns wanted to continue the pursuit, but a recall order from Major-General Morgan Lewis, fearing an ambush, halted the action. General Vincent would disband the local militia, arrive at the farm of Richard Beasley, and establish a new defensive post at Burlington Heights.

Nikon FA – AI-S Nikkor 50mm 1:1.4 – Kodak Panatomic-X @ ASA-32 – Blazinal (1+50) 10:00 @ 20C

Zenza Bronica SQ-Ai – Zenzanon-PS 65mm 1:4 – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 7:00 @ 20C

Leitz Leica M4-P – 7Artisans DJ-Optical 35/2 – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-320 – Ilford Ilfotec HC (1+47) 8:30 @ 20C (Constant Rotation)

Commodore James Lucas Yeo had been sent to Canada to take command of the naval establishment on the Great Lakes. He had grand plans to expand the small navy on the lakes in North America from Kingston. He had started the construction of two new vessels, the Sir Isaac Brock (destroyed at York) and the HM Sloop Wolfe at Kingston, to replace the ageing and falling apart HM Sloop Royal George. Commodore Yeo, along with General Prevost, took General Vincent’s message as an opening to cause significant damage to the US Navy by attacking Sacketts Harbor and, for Yeo, the destruction of the US Corvette General Pike under construction as Chauncy’s new flagship. The combined force arrived near Stoney Point on 28 May, and the army began to land shortly after noon. But when sails were spotted, Prevost ordered a retreat, fearing that Chauncy’s squadron was returning. A detachment from the Glengarry Light Infantry was deployed aboard a gunship accompanied by a group of Indigenous troops to investigate. The sails were a flotilla of bateaux carrying new recruits for 9th and 12th US Infantry regiments heading for Sacketts Harbor. The troops landed and engaged the Americans, with the Indigenous warriors giving chase through the woods; the fight was short and sharp, with the Americans surrendering, although some would escape and make it back to Sacketts Harbor to raise the alarm. At Sacketts Harbor, Lieutenant-Colonel Electus Bakus sent word to Brigadier-General Jacob Brown to call up as many militia as he could muster to meet the British attack. Since the failed attack by the British in the previous year, the defences of Sacketts had been improved, with a new line of earthworks, fortifications, and blockhouses constructed to defend the town from a landward attack and two artillery forts defending the harbour from the waterside. Prevost’s delay resulted in the town being better defended by the time the squadron arrived on 29 May. As the troops began to affect their landings on Horse Island, Yeo hoped to move his big ships in to suppress the batteries at Fort Lewis and Fort Tompkins. The shallow water prevented his ships from manoeuvring close enough to provide practical artillery support. The British forces made quick work of the small force of the Albany Volunteers defending Horse Island before charging across the causeway to the mainland to attack the town from the landward side. The infantry could make it across the causeway. The water levels prevented the pair of field guns from making it across. Again, the militia fell back in disorder, only to find the arrival of General Brown, who quickly reestablished control and established cover behind the fortifications. One ship, HM Schooner Beresford, managed to move in close to fire on the naval establishment using oars and opened fire, sending the troops manning Fort Tompkins scrambling. One shot landed in the naval yard, which caused the sailors to raise the alarm that the town had fallen and British troops were moving up. Rather than allow the supplies and the General Pike to be captured by the British, both were put to the flame on the orders of Lieutenant John Drury. The opposite was true; the British were locked in a stalemate, lacking artillery support. General Prevost ordered a retreat, which was reported officially as being orderly, while the opposite was again accurate. The infantry fell back in disorder and returned to the ships before additional American regulars from the 9th US Infantry arrived. When word reached the naval yards, the fires aboard the General Pike were put out, and the ship was saved; the supplies, however, were a total loss

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+9) 20:00 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+9) 20:00 @ 20C

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+9) 20:00 @ 20C

When word of the attack reached Commodore Chauncy, he immediately made sail to Sacketts Harbor, leaving the army in Niagara without any naval support. Commodore Perry was released to return to Lake Erie, bringing two schooners and their crews in an overland engineers feat from Niagara to Black Rock. The Americans would extend their occupation across the peninsula and began to organise an attack against Burlington Heights. General Vincent had started fortifying the Heights against a landward and lake attack. While the fortifications were simple, the heights offered a defensible position. General Prevost would not face any consequences for his actions at Sacketts Harbor. His reputation and standing in the eyes of Commodore Yeo would grow into a rift between the Army and Navy that lasted through the rest of the conflict. General Sheaffe would be removed from his duties as commander-in-chief in Upper Canada and relocated to command the garrison at Montreal. Replacing Sheafe, Major-General Francis De Rottenburg, another career officer with a noted focus on light infantry tactics, something that could prove useful in the disorderly war happening. For the British, the first part of the year proved bruising; the loss of York and Niagara, plus the failures in the west, would take decisive actions to reverse course and regain Upper Canada.

Rolleiflex 2.8F – Carl Zeiss Planar 80mm 1:2.8 – Kodak TMax 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak TMax Developer (1+9) 20:00 @ 20C

Sony Cybershot DSC-WX7 – Carl Zeiss Vario-Tessar 2,6-6,3/4,5-22,5

Nikon D750 – AF Nikkor 14mm 1:2.8D

Many of these battles through the winter and spring of 1813 are well commemorated across Canada and the United States. In some cases, you have to go looking for them. The River Raisin battlefield is now a National Historic site operated by the National Parks Service in Monroe, Michigan, south of Detroit. The site has a small visitor’s centre, a historic plaque, and a unique example of a sled-mounted artillery piece. The centre lays out the battle with an interactive map and displays of artefacts from battlefield archaeology. It also hosts an annual battle reenactment. Today, Elizabethtown is known as Brockville; the town changed their name to honour Major-General Sir Isaac Brock in mid-1812, although it would be several years before the name was officially changed. Sadly, there is nothing in the town to mark the raid. Similarly, no buildings from the battle survive in Ogdensburg, New York. However, using information plaques, you can still follow the British route through the streets. There are still some surviving earthworks from Fort de La Présentation, where the American guns were mounted. The town hosts an annual reenactment even in February. I’ve had a chance to participate once. On the Canadian side, Fort Wellington in Prescott, Ontario, is a national historic site operated by Parks Canada and restored to how it appeared in the late 1830s. It does tell the story of the fort’s involvement in the War of 1812. The Battle of York is well-marked throughout the city of Toronto. The original garrison location is now a condo development; the rebuilt Old Fort York is a city-operated museum. It has some of the oldest buildings in the city, including two blockhouses and the brick magazine from 1813, plus several other buildings that were added post-war. You can also find detailed information about the Battle of York and a surviving “Simcoe Gun” that was part of the defense. A Lion Memorial near the leading battle site is located outside the Liberty Grand Event Space on the CNE grounds. Also nearby is the memorial to Fort Rouillé, where another action happened. The Defenders of York memorial can be found in Victoria Memorial Park between Bathurst, Niagara, Wellington and Portland, and a modern monument erected in 2008 and designed by Douglas Copeland is found at Bathurst and Lakeshore. The original Upper Canada Mace was returned in 1934 and is now displayed inside the Ontario Legislature (Queen’s Park). Fort Meigs in Perrysburg, Ohio, was reconstructed in the 1960s and hosts an annual siege event every Memorial Day long weekend. I had a chance to attend the event once, it was cold and wet and right on par with how the historic siege was weatherwise. The site is well constructed to reflect how the site looked during 1813 and is littered with memorials to the battle, the largest being an obelisk erected in the early 20th Century by Civil War veterans. You can also find two surviving gun pits south of the fort in the Fort Meigs Union Cemetery north of OH-65. North of the Maumee River in Maumee, Ohio, is Fort Miami Park, with some remaining earthworks from the Northwest Indian War era fort that the British used, including a plaque to the 41st Regiment of Foot. Sackets Harbor has a massive collection of war-era and post-war buildings, and last year, it hosted a grand tactical event for the War of 1812 reenactment hobby. I have had a chance to visit Sackets but sadly did not spend enough time as I was in a time crunch. Having interpretive plaques, markers, and volunteers throughout the site is well worth the effort. Also, make sure to visit the Military Cemetery on Spencer Drive where the mortal remains of General Pike can be found. Similarly, the Battle of Fort George is well marked throughout Niagara-On-The-Lake with the historic fort having been rebuilt in the 1930s to how it would have stood in 1813 and a memorial marker is found near the American landing site east of the public golf course. The march of the 104th is well documented, with a memorial erected in 2014 at Officer’s Square in Fredricton, New Bruswick. A second plaque can be found at Fort Ingall in Cabano, Quebec.