Slavery is an ugly word and one sadly we here in the 21st Century still struggle with, both as an institution and a sticking point in the history of both Canada and the United States. And in any discussion about the pre-confederation history of Canada slavery is something that is intertwined with the increase in diversity in the population of the province and many who once were slaves impacted the province through their actions. Since the creation of the Act to Reduce Slavery in 1796 and the general emancipation of black slaves in the British Empire in 1833 provinces of the Empire provided new hope for many still enslaved in the United States. Communities grew up, such as the Queen’s Bush, and Dawn grew out of the desire to form their destiny and carve out a community of their own. And the British-American Institute in Dawn, which opened it’s doors in 1840 provided education to all former slaves beyond that of farming. Graduates and men from Dawn were held up as examples of artisans second-to-none. And while I may be portraying Canada as a haven free of anti-black racism, don’t whitewash the situation. Canada was ripe with racism, many were forced to live as second-class citizens, often banished to the outskirts of major urban centres living in little more than shacks, and this despite the passage of many anti-slavery laws by the Empire and the Province. As a white man, I cannot begin to imagine what such a life would be, having escaped to freedom only to face some of the same situations in what was considered freedom.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

But not all citizens of the Empire held the attitude that those of colour were lesser, like many who worked to end the institution of slavery in the United States, there were many in Canada and the Empire who fought for the same thing. Reverend William King proved to be such a fighter. Reverend King had a crisis on his hands. He had recently learned of his father-in-law’s passing and that his entire property was now his property, which included both land and slaves in Louisianna. As a member of the clergy of the Free Presbyterian Church, he could not own slave, and if word reached the Church, he could be removed as a minister. It all started back before his ordination when he served as headmaster of a school in New Orleans and met and fell in love with the daughter of a wealthy member of society, one Mary Phares. When they married, her dowery included both land and slaves. King, already an abolitionist had no way to free these men, now his property under American law, nor could he pay them also illegal. He also refused to sell them, fearing for their safety. King, would carry on, treating all who worked for him fairly. In 1844 he would leave for Scotland to seek ordination and turned all his property over to his father-in-law. As he studied, he received the horrible news that he lost his wife and many of his children. Nevertheless, he continued his studies and in 1846 ordained as a minister and sent to minister to a congregation in Toronto. Here he learned of his father-in-law’s death and began to formulate a plan after learning members of his extended family wished to purchase the property. He did not hide the fact that he now owned slaves and approached the church openly but presented a plan to them. King’s project involved purchasing a large tract of land near Chatham and there establish a community which former slaves could buy a plot of land and build a new life for themselves in freedom, and the first men would be those whom he now owned. The church granted his wish, and he went to the United States. It must have looked strange to see a well dressed white man escorting a group of black men without chains as they headed north on the Mississippi River. King would declare the men free in Ohio (a free state) and leave them in the care of his family there to learn some skills in farming and climatisation to the colder climate, while he proceeded back to Canada to set things in motion.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

King proceeded to use his influence in the Church and even sought the help of the Governor-General, Sir James Bruce. Both proved beyond helpful in providing financial and legal backing for the idea. But not all desired a community of blacks in their district. Those against the settlement rallied around Edwin Larwell, a hard-line tory which was among those who had not supported the move towards Responsible Government. King, undaunted, arranged for a public debate between Larwell and himself. The discussion took place in Chatham on the 19th of August 1849, and while many of Larwell’s supporters had threatened violence, King did not back away and even allowed for supporters on both sides to attend. Larwell and his supporters came up with a list of requirements for those of colour who would settle in Elgin. They called for segregated schools, voting restrictions and reexamination, payment of additional taxes and posting bonds, and disbarment from public office. King cooly defended his plan even when faced with the jeering crowd, using the Dawn settlement as an example that such a community would only add to the area and bring value. Larwell’s demands would be ignored and on the 28th of November 1849 King officially founded the Elgin Settlement. But those who had supported the community had a set of rules for the residents. Any who wished to purchase land must be a former slave who had escaped to freedom. The new owner could not lease the property to anyone else until they had repaid the small mortgage. The owner must build a house, garden, and farmland. It proved to be a great example of keen urban planning that allowed the community to flourish under local leadership. Reverend King would plant a Free Presbyterian Congregation in the form of St. Andrew’s Church and soon a congregation of the American Methodist Church arrived. The locals built mills and a school, the mills providing additional employment and the school taught both children and adults. Many children graduated from the school went on to learn at the many universities in the province. The local government decided to rename the settlement after Foxwell Buxton, the British Member of Parliament who sponsored the British emancipation bill in 1833. And by the peak, the community of Buxton supported mills, farms, and brickworks with a population of 1,000 men.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

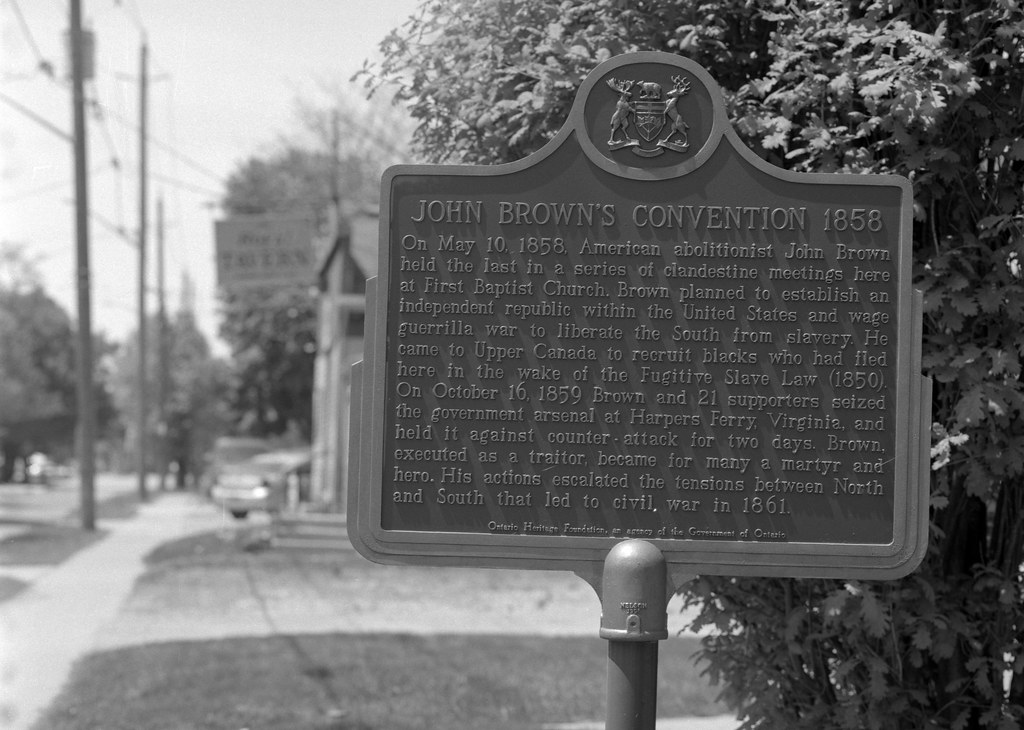

By 1850, escaping to freedom proved far more difficult as the Fugitive Slave Act gained new teeth. Anyone found helping slaves could face criminal charges, and the recapture of slaves made a Federal responsibility. Additionally, some slave catchers proved far more ambitious and pushed into Canada, hunting those who had crossed the border to gain freedom. Thankfully the Empire and the Americans never came close to war over these invasions, and many catchers found themselves helpless in Canada with many refusing to help or running the men out of town. And many who once maintained their freedom in the northern states began to fear for their safety and decided to escape to Canada. The Underground Railroad continued to operate despite the threat to all who worked the network, but even the railroad’s famous conductor, Harriett Tubman moved to Canada. Tubman and her family settled in St. Catherines in 1851. Like many port cities in Canada St. Catherines held a large community of former slaves and free black men. Tubman worshipping at the local congregation of the American Methodist Church. The opening of the Great Western Railroad Bridge in 1855 proved an additional help to many seeking to escape the United States by walking across the bridge or hitching a ride on a train. But for some the only way to end slavery would be through force of arms, John Brown soon rallied many around his cause to start a revolt and start a free country and an enclave of the United States. Brown’s planning began in 1856 and within two years gained a large cache of guns, ammunition, money, and men. But he thought that he could drum up support among the community at large, specifically in Canada. On the 10th of May 1858, he opened a constitutional convention at First Baptist Church in Chatham. Nearly a third of the communities 6,000 residents were former slaves. Brown spoke at length on the goals of the new nation. Among those would attended was Harriett Tubman and while the exact number of those who pledged support is unknown, a year’s delay caused many to dismiss the cause. Brown would eventually launch an unsuccessful assault against Harper’s Ferry on the 16th of October 1859, leading to his capture, arrest, and execution on the 2nd of December.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

But in the United States, a group of seven slave-owning states, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana decided to split from the United States to form the Confederate States of America on the 8th of February 1861. While the Washington government refused to accept them as an independent nation the slow march to war had begun, ending in the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861 starting the American Civil War. Many former slaves would begin to return the United States, many joining the Union Army to fight for their freedom and reunification of their Country. And while the Civil War proved a catalyst for Canadian Confederation it also marked a low point in Anglo-American relations since the end of Rebellions in 1838. The population of many black communities took a nose dive and continued even after the war’s end in 1865.

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Today the rich history and diversity brought by those men and women who fled for their freedom are well remembered across Ontario. While Buxton is a shadow of its former self, having split into North and South Buxton. Much of the site’s history and that of the Underground Railroad can be found at the Buxton National History Site. The location has a museum, several buildings from the original settlement including an example of the house that was required to be built by any landowner and is located in North Buxton. Each year on Labour Day weekend the site hosts a homecoming for the ancestors of those first residents to come back and celebrate. King’s church, St. Andrew’s remains an active and thriving congregation in South Buxton and is a part of the United Church in Canada today. First Baptist Church in Chatham, Ontario still stands today and has a small museum to Brown’s convention and an Ontario Historical Plaque stands outside the church. In St. Catherines the church where Tubman worshipped still stands, the Salem Chapel saw extensive restoration work from 1957-9 and still operates as a congregation today. A museum to the church’s role in the Underground Railroad and a memorial bust to Tubman can be found. A memorial to those men who as former slaves returned to the United States and fought for the Union Army can be located in Washington DC near the U Street Metro Station. A twin memorial to those who escaped to freedom stands in Detroit, Michigan and in Windsor, Ontario the memorials can be seen from the other to form the complete memorial. The most significant memorial is those who thrived in Canada, and who contributed to our nation and continue to do so today. But even still today both here in Canada and the United States the shadows of slavery and the division is caused are still things we struggle with today, in how any person of colour is often looked down on or mistreated. It remains an ugly stain on both Canada and the United States and one we must come to terms with before we can move forward. But this is not my story to tell, I simply tell Canada’s story as best I could if you want to see what it was like, really like and from the proper perspective I urge you to read this hard to read an article by Michael Twitty, shared by my dear friend Martha.