If there is a singular group that I had a clue about going deep into this project, that group would be the Family Compact. And how you view them relies on your view of Canadian History. To some they are the antagonist of this particular branch of Canadian history, to others, they represent Canadian loyalty to the British Crown in the rebellions. But for me, they now stand as the opposite side of the same coin during the Upper Canada Rebellion. The Compact represented the colonial elite, the new ruling class. They controlled every aspect, every part of the government, the law, and the church. Many were part of the government, the law, and the church, freely elected and allowed to remain in their posts. Alliances meant you would get ahead; opposition was nothing short of political and social suicide. They could trace themselves to the first loyalists to come to Upper Canada in 1791, and they used that power to maintain provincial loyalty through manipulation, and this was allowed, by law, and even encouraged.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

The formation of this cadre of men did not happen overnight, like any circle of power it took some time to grow. But it can trace itself back to the first group of men whom John Graves Simcoe appointed into the higher offices of the Provincial Parliament in 1794. Under the Constitution Act, the letter of the law did not forbid cross-appointments, but the spirit of the law did call for separation between the Legislative Council and Executive Council. And in the 1st Upper Canada Parliament, that met at Newark, today Niagara-On-The-Lake, Ontario, four of the five members of Simcoe’s Executive also sat on the Legislative Council. These men were more than happy to serve as service on these two councils not only gave them to power to direct the Province in their favour it also helped them influence the Lieutenant-Governor. And as long as they remained loyal to the Crown and the taxes flowed to England, the Colonial Office remained happy. The office even promised the creation of a local aristocracy complete with titles which could be passed down from father to eldest son. But these men did not need ancient titles they had a new power for the new world, and that power was money. These men used their influence and power to ensure they controlled the dominant economy in Upper Canada and the vast tracts of untouched land proved rich in natural resources such as fur, timber, and wheat. The extraction of these resources filled the docks at the major ports of Montreal and Halifax where their peers were more than happy to send it back to England to drive the home economy. They created their new aristocracy, the merchant baron. And other governors were delighted to go along, as the taxes kept flowing, the Province stayed loyal, which meant they would maintain their position and possibly advance their social standing at home. And when the Colonial Office saw this, they to were happy to continue with the model and even encouraged its spread. These groups of Colonial Elites would spread and form in the other provinces, notably Lower Canada.

Intrepid 4×5 – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 – Kodak Plus-X (PXE) @ ASA-64 – Blazinal (1+100) 10:00 @ 20C

The most significant ally in the early 19th-Century was Francis Gore, he not only encouraged but helped expand the reach of these elites, and they were more than happy to line his pockets with extra income. And in return Gore would ensure that they kept their positions of power, got the top choice in land and appointments. And appointments to their friends and allies were also granted to provide the wealth held within a small loyal group. The war, however, changed everything, Sir Isaac Brock had no desire to help the elites, he had something more significant to worry about, and as Brock was not the Lieutenant-Governor, he was merely the President of the Executive Council. The elites were more than happy to go along with Brock and other Military governors and used to war to build their social standing. Usually through appointments to high-ranking positions within the local militia. The war, however, did shape many of their views of the British military especially because of General Roger Hale Sheaffe’s actions during the Battle of York in 1813. At the climax of the battle, rather than make a final stand, General Sheaffe ordered all the British troops to retreat to Kingston, destroying both the grand magazine at the town garrison and destroying the bridge over the Don River. To add insult, he left the surrender negotiations to several members of the local militia, Colonel William Chewette, Major William Allen, and Captain John Beverley Robinson. He was watching over the disaster, Reverend John Strachan the local Anglican priest who offered to help several of his former students. Strachan to the up-play the role of the Militia would often publicly speak of how the War had been won not by the brave efforts of the British Regulars but the tenacity of the Canadian Militia. In the post-war era, the men worked endlessly to reestablish their control, and with the return of Francis Gore, they had no issues bringing about total control over every aspect of the Province. By the 1820s, they controlled Provincial Justice, the Church, Schools, Business, Land Use, Banks, the Militia, and the Government. They had their people everywhere, and everyone owed their allegiance to the core few.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

It would be in 1824 that this elite group of men got their name, The Family Compact. The name credited to Marshall Spring Bidwell in a letter to John Rolph offering his help to rid the Province of the evils wrought by this Family Compact. The title itself is misleading, while there were some familial connections between the members, they were a family less in blood more in loyalty. The Family Compact was the original old-boys club. And while their numbers exaggerated by the Reform Newspapers, notably William Lyon MacKenzie’s Colonial Advocate their membership numbered ten men. At the head of the compact, Chief Justice John Beverly Robinson. Robinson born in 1791 in Lower Canada could trace his family back to some of the first families to arrive in Virginia. His teaching fell under Reverand John Strachan, and he studied law under D’Arcy Boulton. During the war, he served in the York Militia serving at Queenston Heights and York. He is best known however for leading the Bloody Ancaster Assizes of 1813 after being appointed Acting Attorney General at the death of John MacDonnell. He sentenced seven men to death during the trials. He would see election to the Legislative Assembly after the war. Next to Robinson would be his teacher, Reverand John Strachan. Strachan, born in 1778 in Scotland. He arrived in Upper Canada and made a name teaching the young children of prominent families. He would use his influence both in the schools and the pulpit to ensure that other denominations, especially Roman Catholicism. He also served on the Executive Council of several Governors and used that influence to keep the Anglican Church in the forefront for Upper Canada and power in the local schools. The Compact also controlled the militia through the connection of Æneas Shaw and James FitzGibbon. And membership in the group did not stay closed; the men were always seeking other members to join, oddest of all was Allan Napier MacNab, who used the group only to further his power and standing within the Province. Others like William Allan who controlled the Bank of Upper Canada and later Colonial Expansion through control of the Canada Company. And trade with William Hamilton Merritt owing the Compact for their granting of capital to build the Welland Canal. Even William Chisholm knew he had to ally himself with the Compact to push through his request to purchase land at the mouth of the Sixteen Mile Creek and saw the founding of Oakville. And while these men were named with the compact, they were only allies of the group, not actual members. These men were not family, but still had that bond of brotherhood, bound by loyalty, ideas, and ideology of how things must be. They desired unwavering loyalty to the Crown, not the province, to the Church of England, and to that idea of the Ancien Régime. The Compact found their twin in Lower Canada in the form of the Chateau Clique.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

The Family Compact and their Supporters, the Tories were often faced down by men who held different ideas on how the province should run, men like Robert Gourlay, the Baldwins, Bidwell, Rolph, MacKenzie and others formed the Reformers. And often the two groups openly fought in the Assembly and even in the Toronto Council chambers. No arena was safe, but the Compact held all the cards and all the power. And they were not above changing the rules to allow them to win and where that didn’t work, they used groups like the Orange Order to force their will upon others. While they held onto power throughout the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-8 ultimately the arrival of John Lambton would spell the end to the Compact. The 1830s brought about a great deal of reform across the world, the passage of the Reform Bill in London and the Rebellions in France the same decade saw that the power of the few and concentration of power would soon end. And while Lambton would dismiss the Family Compact as a petulant Tory Clique, he did not blame them as the root cause of the Rebellions. But the Uniting of the two provinces eventually reduced the powers of the Tory elite although they continued to exert control until 1849 with the arrival of Responsible Government. Although by this point, very few of the members remained in government.

Graflex Pacemaker Crown Graphic – Schneider-Kreuznach Symmar-S 1:5.6/210 – Kodak Tri-X 320 @ ASA-320 – Kodak D-76 (Stock) 5:30 @ 20C

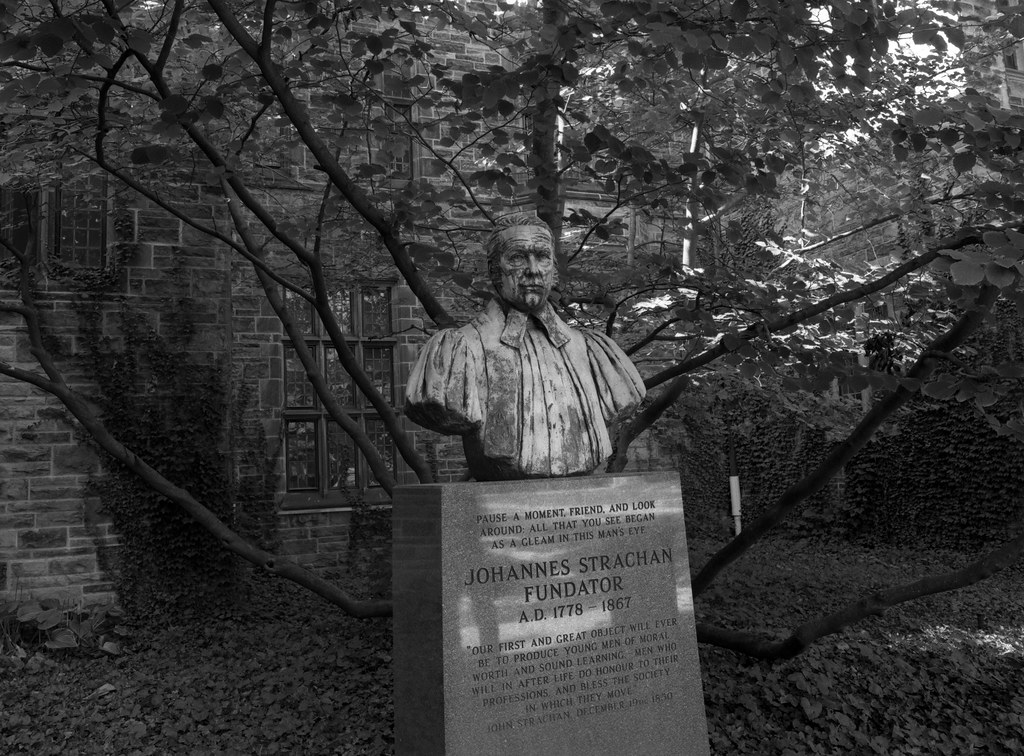

Today the Family Compact is remembered only barely, their members, however, are still held up as upstanding members of Society. If you look closely many streets in Toronto today, bear their names, Beverly and Strachan. D’Arcy Boulton’s House, The Grange still stands today, it remained in the Boulton family until 1910 where it served as home to the Toronto Art Gallery and the Ontario College of the Art and Design (OCAD). In the 1960s the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) restored The Grange to how it appeared in 1835, and today it is home to the Norma Ridley Members Lounge. Sir John Beverly Robinson became a Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1850 and a baronet in 1854. Despite everything he continued to serve in the Justice System until his retirement in 1863, he would die that same year in February. His retreat and library also called The Grange is now home to Heritage Mississauga and their extensive library which has helped in the creation of this project. Bishop Strachan would leave Provincial Politics but continue to influence his former pupils and Compact members. He would continue to live in his grand home in Toronto, the Bishop’s Palace, and ultimately die in the City on the 1st of November, 1867 and is buried beneath the cathedral of St. James, the church he helped build. He is also remembered by a bust in the quad of Trinity College, a part of the University of Toronto, the school he helped to found. Ultimately the Family Compact would show precisely how extreme views can stifle and prevent growth and change, but their conservative opinions must not be dismissed either, and many who held onto a moderately conservative view would go on to help create Canada as we know it today.

3 Comments