Politics, in general, can be rather dull. I’m sure only pundits and political science students watch CSPAN regularly. When I attended a question period in the House of Commons in Ottawa, Ontario, it proved so dull that even the Prime Minister appeared to be napping. Yes, tales of military might, bravery, heroism, and battles make for more exciting reading and writing. We cannot ignore the political history that shaped pre-confederation Canada. Because much of this early dealings helped shaped our country’s government today, yet if you look closely you’ll find a bit of exciting. Like how the arrival of democracy resulted in riots only seen on the news in eastern European nations the decade that followed proved to be filled with intrigue and scandal that would make our modern analysts, hosts and pundits scrambling for their social media accounts. Decrying the government and laying the blame on their political opposites. Despite their hard-won victory, Robert Baldwin and Louis La Fontaine maintained their hold on the government. They had no party, but rather a group of representatives from all sides of the political spectrum, the idea of unity and restraint remained their goal. But not everyone felt the same way; Sir Allan MacNab maintained his hold on the Conservative stalwarts. Joseph Louis Papineau had brought together some of the radical in the reform wings of Canada East forming the Parti Rouge, opposite of the conservatives under George Cartier and the Parti Bleu. Peter Perry, disgruntled at the lack of movement from Baldwin and La Fontaine took the radical wing of the reformers and formed the Clear Grits. And while the two father’s of Canadian democracy held on it was apparent their hold was slipping and without any real oversight from the Crown. Things, it seemed were moving back into chaos.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

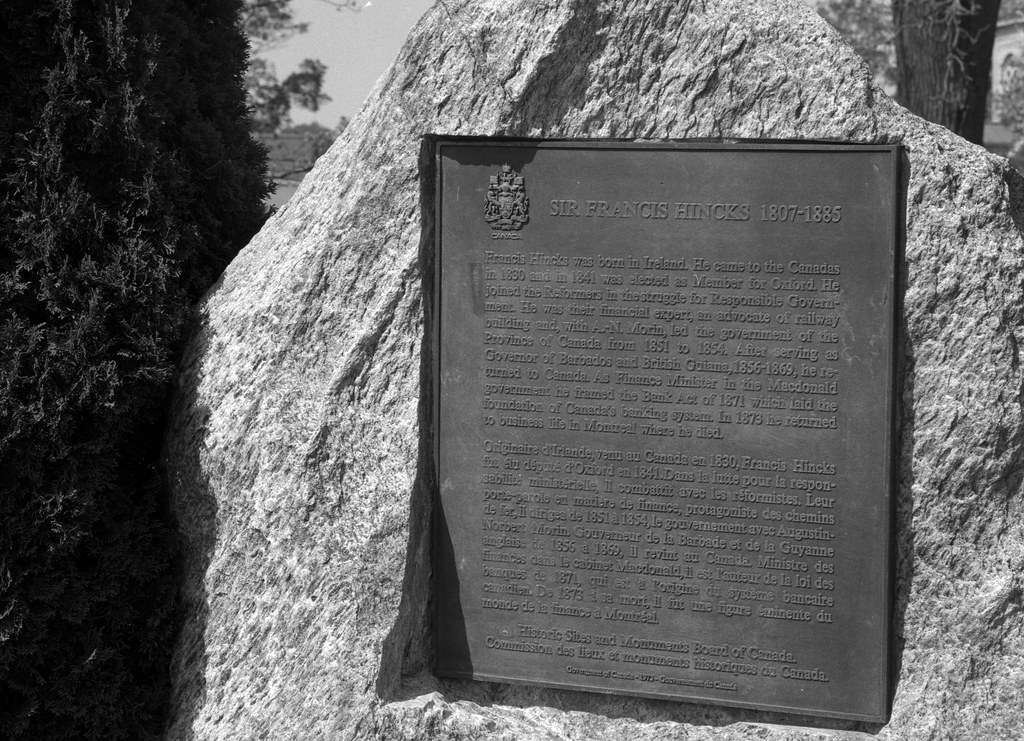

It probably did not help that in 1851 into the fray came back two significant opponents of Robert Baldwin. George Brown, the owner of the Globe Newspaper in Toronto, had a bone to pick with the Reformers having been snubbed in the past by Francis Hincks, Baldwin’s second in the government. Brown had his ideas about moving forward in the independence of Canada. Brown also felt that French-Canadians held far too much influence over the affairs of Canada West and was stanchly anti-Catholic. Brown quickly joined up with the Clear Grits. The second one to return to the assembly proved a wildcard. Having been pardoned and moved back to Canada, William Lyon MacKenzie also won a seat in the assembly in 1851. He immediately returned to his old ways; the former firebrand attacked anyone who crossed his path. He latched onto Brown’s anti-French and anti-catholic views, called out the Clear Grits and even Baldwin for selling out the cause of reform, calling any who served in the government or the grits shams. But both men found a familiar opponent in Baldwin. Brown attacked the Premiere on his lack of movement on the Clergy Reserve and MacKenzie rooted out a bit of corruption with Baldwin’s choice of heading the Court of the Chancery who used the body to line his own pockets. Rather than address these attacks, Baldwin, caught in the middle of an increasingly hostile assembly took the matter personally. Instead of addressing things in the assembly, he resigned as did La Fontaine a few months later. With the government collapsed, the Governor-General called for general elections. While La Fontaine retired from public life, Baldwin would run in the election, and lose his seat. He retired from public life. Left holding the bag was Francis Hincks and Augustine Morain. The hastily formed reform party took heavy losses to the Grits but held onto a slim control of the government and Hincks, and Morian were appointed as Premiers.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

The only one to stay outside party lines remained MacKenzie, although he had been courted by both the Reformers with a plum job offered up by MacKenzie’s old ally John Rolph and by Brown and the Grits. MacKenzie refused both not wanting to restrict his ideology. Hincks and Morian knowing they held power by just a thread, decided to seek out an alliance with another party within the government. Their first and obvious choice was the Grits, but MacKenzie quickly soured the relationship between Brown and Hincks. But another ally stepped in a strange bedfellow for the reformers. Sir Allan MacNab and the few remaining moderate Conservatives, but MacNab wanted to more than just an alliance he offered to merge the two parties. Despite misgivings and several members flocking to the Grits, the moderate conservatives and right-leaning Reformers formed the Liberal-Conservative Party in 1853. And the work of government continued, the parties worked together and worked on modernising the province. Railroads were built, much the pleasure of both Hinck and MacNab who both were heavily invested in the railroads, Grand Trunk and Great Western respectively. Bills were introduced and passed to repeal the clergy reserve, expansion of the voting franchise, and to allow citizens to elect their mayor directly. Hinck’s crowning achievement would be the negotiation and passage of the first free-trade agreement between the United States and Canada, the Reciprocity Treaty.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

And while things seemed to be going well, at least until MacKenzie uncovered a little backroom deal between Hincks and the mayor of Toronto. An agreement which MacKenzie accused had stolen some ₤10,000 (approximately ₤1.1 million) from the Canadian taxpayers in the sale of railway stocks. Hincks resigned in disgrace, allowing MacNab after years of trying to gain real power finally be appointed to Premiere. But the old Tory was not used to having power and figured it might as well use it as he pleased. Friends were appointed to top posts; finances were left by the wayside. And MacKenzie, fresh off toppling one official went after MacNab and his Attorney General, John A. MacDonald. It also did not look too good that MacNab rarely attended Parliament age and illness all but crippling him. MacKenzie began to speak out about the whole union, declaring the entire idea worthless. He would again raise the idea of annexation both in the assembly and in his small newspaper. In light of the charges of financial mismanagement and misuse of patronage, MacNab resigned. And in 1856 John A. MacDonald, MacNab’s second would take the office of Premiere. The Liberal-Conservatives, now drifting more right, aligned themselves with George Cartier and the Parti Bleu in Canada East. MacKenzie would be the last of the old-guard to leave government, resigning due to age and illness in 1858. And now new people and a strange new idea began to stir within the country.

Nikon F6 – AF-S Nikkor 85mm 1:1.4G – Kodak Tri-X 400 @ ASA-400 – Kodak D-76 (1+1) 9:45 @ 20C

By the end of the decade, the Province of Canada had transformed from a rural backwater to a modern civilised and industrialised province of a modern Empire. Railroads and Telegraphs gave the province a modern mode of transportation and communication. The Niagara Region along with Toronto and Hamilton were centres of population and industry. A small semi-professional standing army showed in the Active Militia although untested in battle stood ready to defend their homeland. And even a permanent capital city had now been selected by the Queen herself, the former community of Bytown now called Ottawa and designs for a grand Parliament building on the old Barracks hill were coming together. Robert Baldwin would die in Toronto in 1858, his friend an ally Louis La Fontaine did not stay far from the public eye seeing an appointment as Chief Justice of Canada East dying in 1864. William Lyon MacKenzie managed to reconcile with both John Rolph and George Brown before his death in 1861. Sir Allan MacNab would be appointed to the Legislative Council in 1860 and would die two years later in 1862. The only member of the old guard that would survive to see the creation of the country of Canada was Sir Francis Hincks, having been found not guilty recovered and saw the appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of Barbados in 1856 and British Guiana in 1861. Returning to Canada in 1869 he served as the Minister of Finance until 1874, dying in 1885.

Pacemaker Crown Graphic – Fuji Fujinon-W 1:5.6/125 – Kodak Plus-X Pan @ ASA-125 – Kodak Microdol-X (Stock) 8:00 @ 20C

Oddly the greatest legacy of this strange decade in Canadian Political history is the Political parties that still exist today in the Canadian Federal Government. The Liberal-Conservatives would drop the Liberal title in 1873 becoming the Conservative Party, a title they maintained until severe losses taking the name the Progressive Conservatives in 1942. The PCs would merge with the Canadian Alliance in 2003 becoming the modern Conservative Party of Canada. They use the colour blue a throwback to the Parti Bleu and maintain the moniker, Tory. Far less complicated are the Federal Liberal Party which grew out of the Parti Rouge and Clear Grits. The two parties merged and took the name in 1867, which has remained unchanged since that year. They are represented by the colour red and often are referred to as the Grits. And while our political dealings are far less exciting they remain much as they did in the past, infighting and inter-party fighting and scandal still make the news as they did over one-hundred and fifty years ago.