The year was 1865, the American Civil War had ended, and four British Provinces in British North America decided to unite under what is called Canadian Confederation. And a large group of Irish Americans were wondering what their next step would be, and John O’Mahoney found himself at a crossroads. The Fenian Brotherhood hit its stride during the Civil War and now had money and manpower to spare. Plus all their members who served in both armies during the war had either kept or purchased their own equipment, the Fenians had an army that could easily stand up to the American Army of the day. The trouble was what to do with them? O’Mahoney wanted to keep the model where the money would be sent onto John Stephen’s and the Irish Republican Brotherhood, however, Stephens saw the army as a way to realise the goal of Irish independence. Stephens wanted to see the Fenian army sail across the ocean and invade Ireland. Confident that such an army would easily overwhelm any local garrisons, plus he expected the Irish to rise up and join in the revolution. But the greatest threat of O’Mahoney’s authority in the United States came from within the Fenians in the form of William Roberts. Roberts had a different plan, that was to invade and hold key cities, canals, and rail lines then ransom them for Irish independence. Stephens would speak in favour of the Roberts plan. And while O’Mahoney held onto the presidency, the strength of Robert’s Wing grew. And Roberts would be elected as Head of Centre. This election gave the Canadians pause, Premiere John A. MacDonald would deploy his spies that served to investigate the movements of Confederate agents now tracked the Fenians. The Canadians began to express their concerns to England and asked for them to deal with the Fenians through diplomatic channels. The trouble was that the British were already talking about the Fenians with the American government but through unofficial channels. The request came from the Americans themselves who wanted to keep things on the download, publically the reason was not to anger the Irish-American voters the second was that Anglo-British relations were low in the post-Civil War era. The Americans did make token gestures in seizing Fenians arms, but the brotherhood always got their guns back, either through sympathetic officials or sly lawyers who kept the government tied up in court.

Nikon D70s – AF-S Nikkor 55-200mm 1:4-5.6G DX

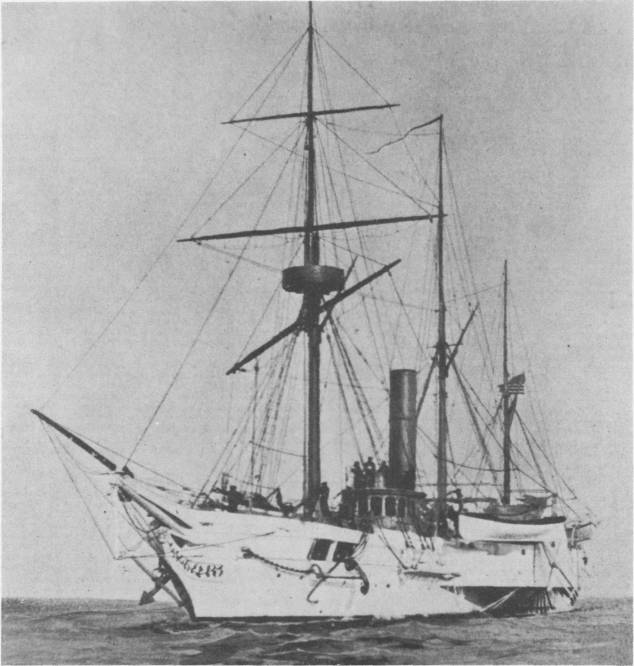

Roberts proved himself a man of action and began to spend much of the money in the Fenians accounts. He purchased arms and bought men, he sent Fenians into Canada as spies or to establish Fenians Circles in major urban centres. While they did not use the term Fenian, they instead would operate under the name of the Hibernian Benevolent Society. One such spy, John Canty, purchased a home in the village of Fort Erie (at that time called Waterloo). He found work as a crew chief for Grand Trunk Railroad working on upgrading the old iron rails of the Buffalo & Lake Huron rail branch that connected Fort Erie to Goderich. His work took him along the entire lower Niagara Penisula and even in site of the Welland Canal. He made detailed sketches and maps of the area. Additional details on the Welland Canal came from a Fenian Circle aboard the USS Michigan (15). But Roberts also began to plan for an all-out invasion of Canada. The irony is that the plan looked similar to that of the Americans in the first year of the War of 1812. The initial invasion would see Fenians cross and take Goderich, Port Colborne, Amherstburg, Windsor, and Montreal. Then move inward taking the Welland Canal, Kingston, the Rideau Canal, Hamilton, Toronto, Ottawa, and Quebec City. And to ensure secrecy, Roberts ensure that the right people were paid and the right eyes averted. The Green Scare of 1866 had the Canadians scrambling the active militia in March to counter a St. Patrick’s Day invasion that never came and a second time in April. In April at least O’Mahoney had launched his invasion which briefly seized Campobello Island in New Brunswick. The Fenians would quickly be chased off by British Regulars and Royal Navy Warships. O’Mahoney’s failure would be on his head, and he separated himself from Robert’s Wing.

unattributed; probably United States Navy [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

And the Fenians prepared for their planned invasion, men trained for battle and women made uniforms and battle standards. Fenian Regiments were raised across all of the United States, and men took on commissioned granted by the Fenian government. Uniforms of the Union and Confederate Armies were pulled out of trunks some decorated with Irish symbols. Others had the buttons replaced with those bearing the initials I.R.B. A call to arms sent the Fenians to their assigned jumping-off points in Chicago, Vermont, Detroit, and Windsor. Smaller groups would head to other cities like Buffalo to launch diversionary support of the major attacks. Everyone was ordered to travel in civilian gear, or travel under cover of darkness. Some even detrained before reaching the main stations in the final city. Irish neighbourhoods swelled as arriving Fenians were welcomed into the homes of their fellow Fenians. But not all went according to the plans, cities like Chicago stood empty, many Fenians in the north did not respond to the call to arms, yet the ones in the south surged north. At Cleveland, two failures would change the course of the planned attack. The first being a failure to acquire boats to transport the army across Lake Erie to capture Port Colborne, the second the failure of General William Lynch actually to arrive and command the army. Here is where Roberts made his mistake, he changed the plan and made the attack on Fort Erie the main push to capture the Welland Canal and sent word for those in Cleveland to move to Buffalo. At Buffalo, Colonel John O’Neill received the good news, he was being promoted to General and would be in charge of capturing the Welland Canal. With reinforcements on their way, the Fenians failed to disguise their movements. The sudden migration of men and arms came to the attention of US Army Commander General Ulysses S. Grant, who immediately alerted the local district commanders in upstate New York. Also the District Attorney and mayor of Buffalo, Sander Wells. Mayor Wells, already a vocal critic of the Fenian movement, found himself neck-deep in the group. But both he and the district attorney knew they could do nothing until the Fenians did something illegal. So they instead cooked up a plan to blockade the city, not to keep people out but to keep the Fenians in, and every night the Michigan would patrol the river to prevent any crossing. O’Neill already had a plan to deal with the Michigan and how to get his men across. Fenians who worked for the Pratt Iron Furnace arranged for a pair of tug boats and four barges to bring the invasion force across under the guise of an employee picnic on Grand Island, and the Fenians aboard ship would handle the US Navy warship.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

The pilot of the Michigan would not turn down a night out with his fellow crewmates, who treated the man to a night of fine whisky, cigar, and the attention of an amorous young woman. As the time came to launch on patrol, it became clear that on the night of the 31st of May 1866 the Michigan would be staying in port that night. Lieutenant-Colonel Owen Starr, having stolen a pair of small craft slipped across the river unhindered landing just above the village. The vanguard quickly securing the small dock marched towards the village with haste, but altered a pair of men who had been fishing in the early hours before dawn. John Canty waited for them to guide them further into the village. But the alarm had been raised and a telegraph operator in the Grand Trunk Yard in the village began to tap out warnings on his telegraph machine. The first to the rail ferry International to sail out into the middle of the river and hold there fearing it would be captured and used by the Fenians. Second to Toronto to warn of the invading army, and third to signal the train waiting in the yard to drive out with haste to Port Colborne out of the Fenian’s hands. All three transmissions made it out before Starr’s men cut the line. As dawn rose, the main body of Fenians began their landing at Frenchman’s Creek, marching into town. The town garrison, a small detachment of men from the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment surrendered the ruins of the Old Fort to the Fenians. O’Neill ordered the town leaders onto the main street. He aimed to assure them that the Fenian’s quarrel was not with them, but with England and if they did not resist or cooperated, they would not be harmed. Most would agree to the terms and opened up the various hotels and public houses to feed breakfast to the army. The odd thing was that the town stood mostly empty, many Canadians having learned of the invasion had fled to neighbouring villages or across to Buffalo for shelter. Many remembering the stories of the American occupations during the last war. O’Neill ordered Starr to cut the rail line to prevent any trains from getting close to the village, and his small force moved forward disabling telegraph poles and burning the rail bridge over the Saurwein River. Some in the town joined the invasion force. Others provided supplies and some horses. O’Neill ordered a small garrison be left in the old fort and marched his army forward to Black Creek.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

In Toronto, Premiere MacDonald stood up before the assembly again calling for a motion to call out the active militia. After being called out twice before on false alarms, many where tired of being called away from family, friends, and work. Because the Active Militia was a volunteer force from the soldiers up to the Officers, in the case of being called out, it affected the economy of many smaller communities in Canada. Thomas D’Arcy McGee joined his voice to MacDonald. McGee, a former Irish revolutionary, warned of the dangers of Fenianism, and their ultimate goal of Irish independence but through military means. McGee had since the failure of the Young Ireland uprising in 1848, and subsequent return to North America had grown tired of the violent turn of the movement and spoke out against the Fenian Brotherhood both before and after his arrival in Canada. Warning telegrams from the mayor of Buffalo helped, and the motion passed. Businesses closed, students and staff put down their books, uniforms and weapons were turned out. Militia units converged on their drill halls and barracks. Commander-In-Chief of the British forces, General George Napier, began to draw up the battle plan. Lieutenant-Colonel George Peacock would be appointed to command the combined regular and militia forces to repel the invasion. Napier ordered the Welland Field Battery to deploy one wing to Port Colborne to report to Lieutenant-Colonel John Soughtan Denis while a second wing to guard the reconstruction efforts at the Saurwein Bridge. Hamilton’s XIIIth Battalion Volunteer Militia of Canada under Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker was to march to Dunnsville and Toronto’s 2nd Battalion Queen’s Own Rifles were to sail for Port Dalhousie then head to Port Colborne by way of the Welland Railway. Napier was to establish his headquarters at St. Catherines with additional regular infantry, militia, and artillery. The only thing missing was cavalry, and troop commander George T. Dennison III of the Governor General’s Bodyguard York County found this rather odd and went directly to Napier. Napier initially refused the assistance of the old militia cavalry unit but did take the suggestion to have Peacock secure the Great Western Rail Bridge at Niagara Falls and establish a camp at Chippawa. But the British were in the dark, completely, they had little more than a map that showed the area’s postal routes and intelligence placed the Fenians at both Frenchman’s Creek and Black Creek. And things were about to get far worse.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 35mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

Colonel Dennis did not appreciate the orders given to him by both Napier and Peacock. And it showed at how the militia troops at Port Colborne were acquitting themselves. Captain Richard King of the Welland Field Battery was at least used to being under the command of Dennis, but the men of the Queen’s Own Rifles did not appreciate being under the command of a stranger despite having a capable commander who was delayed in arriving. To further add to the chaos, Booker, who had been ordered to proceed to Port Colborne brought the XIIIth from Dunsville under orders to bring the Queen’s Own Rifles to Stevensville where Peacock was marching to from Chippawa. Dennis had orders to remain at Port Colborne to defend the canal’s entrance. Peacock also feared the Canadians would not follow his ordered and sent his Aide-Du-Campe, Captain Atkars with written orders. It didn’t help Dennis’ ego that he fell under the command of Colonel Booker, despite being of equal rank, Booker held the rank longer, making him the senior officer. Booker was prepared to follow the orders from Peacock, but Dennis insisted he had better and more recent intelligence to the disposition of the Fenians. He knew that they were nothing more than a drunken rabble at Black Creek and the village of Fort Erie was open for retaking. All the Canadians had to do was take the town and then force the Fenians out of their camp. Dennis also felt that Peacock knew this and was purposefully putting the Canadian militia troops in lesser roles to keep all the glory to himself. Oddly enough, Atkars sided with Dennis and agreed to let the Colonel go through with his plan and communicated this to Peacock at Chippawa. Dennis’ plan also required the use of the Grand Trunk Rail ferry, the International. The trouble was that the ferry refused to budge, having orders from Grand Trunk to stay out of the mess, but Dennis knew someone who had not been called out with the militia. Captain Lauchlan McCallum’s Dunsville Naval Brigade had been standing ready and responded quickly to Dennis’ request, bringing the lumber ferry W.T. Robb to move troops quickly to Fort Erie. Dennis, King, and Atkars boarded the Robb with the Welland Field Battery and the Naval Brigade and left. Missing an angry telegram from Peacock dismissing Dennis’ plan, Booker responded that he would march as ordered. But both Peacock and Dennis had it wrong, O’Neill’s troops were sober and were no longer at Black Creek or Frenchman’s Creek. While history remains unsure how O’Neill got his hands on Booker’s orders, he had moved the army to a ridge above the village of Ridgeway he planned to cut off the Canadians from the British regulars marching on Stevensville.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

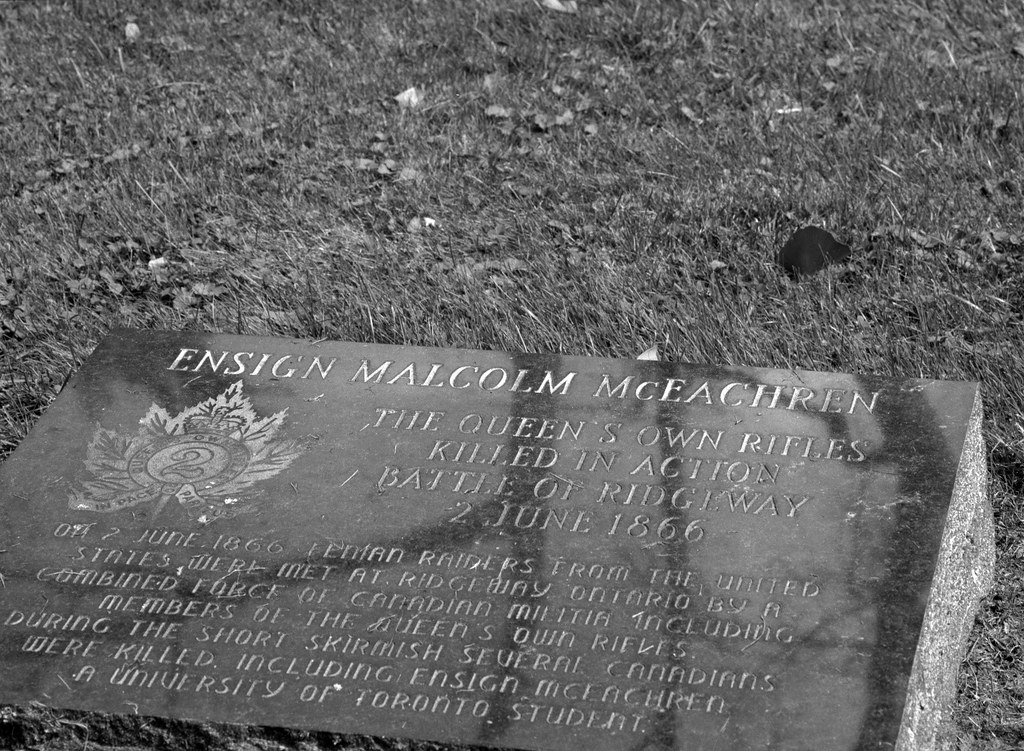

Booker was a modern business owner; he knew that moving goods in a timely fashion was paramount to maintaining customer satisfaction, and he needed to work within the train times available. He also knew his orders and intended to follow them to the letter. Peacock had ordered that Booker should march by 5:30 am if the men’s bread ration was ready. Booker ordered that the bakers make all the bread of the Town would go to those under his command. And with bread in hand, the men of the XIIIth and Queen’s Own Rifles paraded in front of the train station at Port Colborne and boarded their train which left the station at 5:25 am on the 2nd of June. The train would be five minutes out of the station when counter orders arrived by telegraph. Peacock asked for a one hour delay to wait for reinforcements to arrive at Chippawa in the form of Dennison’s cavalry troop. Peacock had not taken into account the efficiency of Booker, and Grand Trunk sent the telegraph on via handcart. Booker was not expecting a fight nor was most of the militia, many having departed their barracks with little ammunition, no water, little rations. Plus the few medics had only what they could carry, or scrounge, and even the surgeons were local doctors who volunteered in the region. The train pulling into Ridgeway a couple of hours after departure and the men again assembled and with the whistle of the train and the bugle note commanding the men to march, O’Neill knew his foe was on the march. Booker at least had the foresight to deploy skirmishers ahead in the form of Number five company from the Queen’s Own Rifles. The number five company stood out among the militia units present, unlike most units which used the single-shot Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles, they had the Spencer Repeating Rifle. The Spencer featured an internal magazine that held seven rounds and reloaded with a leaver action, giving a clear advantage of the most single-shot rifle of the day, the problem was that they had little training and little ammunition with the Spencer. It would be these skirmishers that faced the first attack, and shots rang out from behind fence lines along Garrison Road. The Canadians took cover and returned fire, the company commander, Ensign Malcolm McEachern, ordering the men to pick their targets and conserve ammunition. But the Fenians it seemed were not up for a fight and kept on falling back, allowing the Canadians to push forward, taking fence line after fence line. As the action grew, a winded Grand Trunk employee arrived with Peacock’s telegram. Booker hastily scrawling a reply with a borrowed pencil and a scrap of paper, the only thing legible would be the time of 7:30 am. As Ensign McEachern leaned out to pick a target, a Fenian bullet struck him, and at the age of thirty-five, he became the action’s first casualty. Booker would have no choice and committed most of the Queen’s Own Rifles, companies one, two, three, four, six, seven, and eight along with the smaller militia units the Caledonia and York Rifles to aid the push.

Sony a6000 – Sony E PZ 16-50mm 1:3.5-5.6 OSS

What the Canadians did not realise is that the Fenians were purposefully drawing the Canadians into a trap, a well-defended line across Bertie Road caught the Canadians unaware. And as calls for additional reinforcements and ammunitions reached back to the main body of troops. Booker ordered companies nine and ten from the Queen’s Own Rifles forward along with the full force of the XIIIth. Number nine company of the Queen’s Own Rifles finding a gap on the Fenian flank and charged headlong past the Bertie Road line supported by number ten and charged into the main force of O’Neill’s army. And while the Fenians continued to toy with the Canadians, the arrival of the XIIIth on the battle line changed their attitude. They were not expected red-coated regulars on the line of battle, and O’Neil ordered the main body forward. The Canadians were suddenly outnumbered and faced with the full fury of the Irish invaders directed at the red-coats they so hated. The fighting grew to a static fevered pitch with the densest taking place around the Angur farm. As Booker realised he could no longer remain he ordered a retreat, but now chaos reigned and discipline vanished, the extended battle line ensured that the order would either be misunderstood to push forward, missed, or ignored. The call of cavalry on the field would further damn the Canadians as they struggled to form a square. The Fenians had no cavalry; it was merely the mounted scouts coming to see the battle. But the damage had been done as the Fenians charged forward with bayonets the Canadians ran, equipment and wounded littered the road back to Ridgeway. The final two companies taking up the rear were number nine and ten companies of the Queen’s Own Rifles. The survivors boarded the waiting train in Ridgeway in silence and returned to Port Colborne. Nine men had died in the actions and many more taken prisoners. Some survivors would later recount that O’Neill himself walked among them, complimenting the Canadians on their fighting skills and that they very nearly took the field.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-100 – Kodak D-23 (Stock) 6:00 @ 20C

But for the Canadians, the day would be far from over, but that is a story for next week. For Booker, Ridgeway would be his only engagement. His reputation would be ruined by some of his junior officers and a freelance journalist. They also took shots at the militia, calling the XIIIth the Scarlett Runners and the Queen’s Own Rifles the Quickest out of Ridgeway. And while a court marshall would clear him of all wrongdoing, he would resign the command of the XIIIth and retire from the militia. Moving to Montreal to reestablish a business before his death in 1871. The failure at Ridgeway would lead the way to improve the Canadian Militia by allowing for more and better training to be conducted. The Canadian government would not recognise the actions at Ridgeway until 1899 when they created the Canadian General Service Medal which allowed any surviving Veterans of the Fenians Raids, Red River Rebellion, and North-West Rebellions to apply for the award. The same year the Lime Ridge Monument would be erected on the grounds of the University of Toronto to the men who fought at Ridgeway. The site of the battle wouldn’t be historically designated until 1920. The two units that fought at Ridgeway, the Queen’s Own Rifles and the XIIIth Battalion are still active units with the Reserve Regiments in the Canadian Army. The Queen’s Own Rifles still maintains the graves of their dead at Ridgeway and the XIIIth today is better known as the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry. Both units would go on to fight at Red River and the North-West Rebellions, Boer War, World War One, World War Two and even into the modern conflicts of today and have earned a fearsome reputation as fighters.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

While mostly forgotten, there is plenty to visit related to Ridgeway. The original battlefield stands at the intersection of Ridge Road and Garrison Road (Highway Three) in Fort Erie, Ontario. The Angur farmhouse still stands further up Ridge Road at Bertie. The farmhouse remains a private residence, and it is said to have bullet damage, although I was unable to locate it after asking permission to look. There’s plenty of relics from the battle on display at the Queen’s Own Rifle’s regimental museum in Toronto’s Casa Loma including a Spencer Rifle and Ensign McEachron’s tunic. The names of the dead are listed on the wall of honour at the Moss Park Armoury in Toronto which is home to the Queen’s Own Rifles today. The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry maintains a Ceremonial Guard which portrays the XIIIth Battalion in uniform, tactics, and equipment that would have been used during the Fenian Raids. And the Lime Ridge Monument still stands at the University of Toronto near Queen’s Park Cresent. The remains of the Ridgeway Nine are interred at Toronto’s St. James Cemetary and the Toronto Necropolis and have been marked.

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 45mm 1:2.8 N- Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

Mamiya m645 – Mamiya-Sekor C 150mm 1:3.5 N – Ilford FP4+ @ ASA-125 – Blazinal (1+25) 9:00 @ 20C

Nikon F90 – AF Nikkor 28-105mm 1:3.5-4.5D – Kodak TMax 100 @ ASA-100 – Kodak HC-110 Dil. B 6:00 @ 20C

Their names are:

Ensign Malcolm McEachren

Sargent Hugh Matheson

Corporal Francis Lakey

Rifleman William Smith

Rifleman Mark Defries

Rifleman Christopher Anderson

Rifleman William Tempest

Rifleman H. Mewborn

Rifleman Malcolm McKenzie

Their names liveth forevermore, I will remember them.

1 Comment